Tzlofchad's Daughters and the Master's Tools

Can we make true institutional change?

This is Life as a Sacred Text 🌱, an everybody-celebrating, justice-centered voyage into ancient stories that can illuminate our own lives. It‘s run on a nonprofit, so it’s 100% NAZI FREE. More about the project here, and to subscribe, go here:

In many ways, the Book of Numbers is the end of the Torah's "story." Narratively speaking, the Israelites make it right up to the edge of the Promised Land.

Deuteronomy is pretty much all one big speech by Moses. And then he dies.

So this last major story, here, could not only be considered the end of the Exodus arc, or even the end of Abraham's; arguably, it's the end of the great arc beginning with Creation.

So what's the message, here?

Well, first of all, we must set the stage:

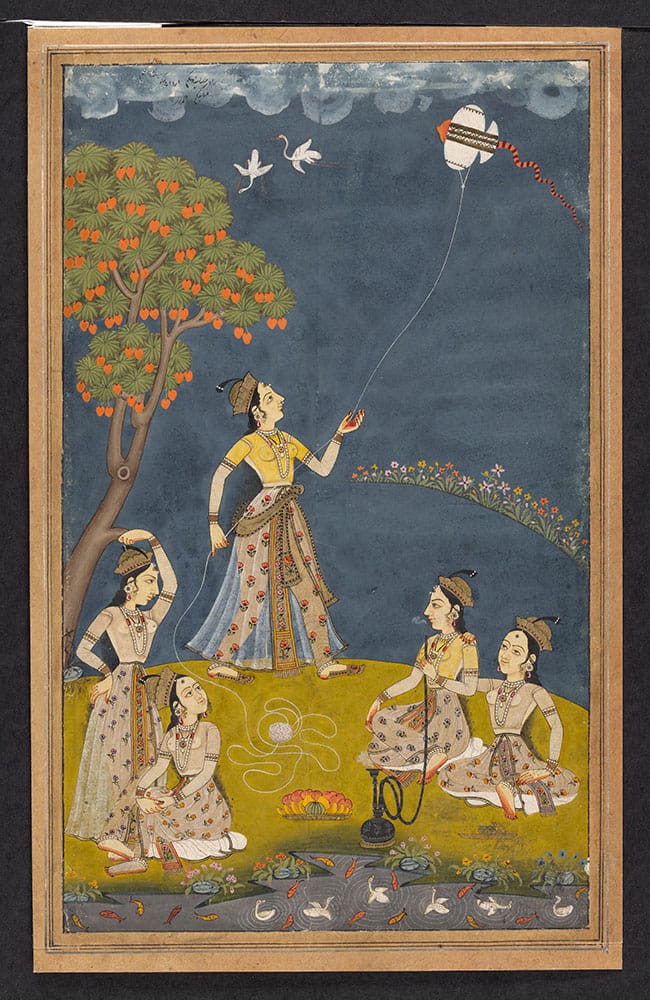

The daughters of Tzlofchad, of Manassite family—son of Hepher son of Gilead son of Machir son of Manasseh son of Joseph—came forward. The names of the daughters were Mahlah, Noah, Hoglah, Milcah, and Tirzah. They stood before Moses, Eleazar the priest, the chieftains, and the whole assembly, at the entrance of the Tent of Meeting, and they said,

“Our father died in the wilderness. He was not one of the faction, Korah’s faction, that banded together against God, but died for his own sin; and he has left no sons. Let not our father’s name be lost to his clan just because he had no son! Give us a holding among our father’s kinsmen!” (Numbers 27:1-4)

We've got these five daughters of Tzlofchad (1) who come before Moses and everyone else, and ask for a deviation from standard inheritance practice at the time, wherein holdings would pass from father to son, and if there was no son, to the nearest male relative. Because women were, in this society, functionally property.

The bravery. Can you imagine?

Gerda Lerner, historian and pioneer of the field of Women's [and Gender] Studies, writes in The Creation of Patriarchy (1983),

To step outside of patriarchal thought means: ...being critical of all assumptions, ordering values and definitions.

Testing one’s statement by trusting our own... experience. Since such experience has usually been trivialized or ignored, it means overcoming the deep-seated resistance within ourselves toward accepting ourselves and our knowledge as valid.

Finally, it means developing ...the courage to stand alone, the courage to reach farther than our grasp, the courage to risk failure. Perhaps the greatest challenge to thinking women is the challenge to move from the desire for safety and approval to the most “unfeminine” quality of all—that of intellectual arrogance, the supreme hubris which asserts to itself the right to reorder the world. The hubris of the god-makers, the hubris of the male system-builders.

Five fatherless women stood before Moses, Eleazar the priest, the chieftains, and the whole assembly, at the entrance of the Tent of Meeting, and they asked to inherit their father's land.

They asked to reorder the world.

And they're identified by ancestor all the way back to Joseph, the child of Jacob/Israel who most challenged gender norms. Huh.

Mahlah, Noah, Hoglah, Milcah, and Tirzah are named, in sharp contrast to many other women in biblical stories.

And these five changemaking women hold the end of this Exodus narrative, just as five women opened it.

Yep, that's right. Remember them? We had Shifra, Puah, Yocheved, Miriam, and Pharaoh's daughter/Batya, each of whom took heroic steps, at great risk to themselves, in defiance of Pharaoh's genocidal decrees. It was their (respective, and sometimes joint) brave civil disobedience that kicked off the eventual liberation of the Israelites from Egypt.

They lied to Pharaoh himself and flouted his explicit orders. They hid babies and made illegal deals to save Israelite boys who have been condemned to death. They exemplifed Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.'s maxim, "one has a moral responsibility to disobey unjust laws."

And now, up on the edge of the Promised Land, we see five women challenging the status quo by going through established chains of command.

They stand at the Tent of Meeting– the communally-accepted site of holiness. They make their plea to Moses, to Eleazar the priest, the chieftains, and the whole assembly.

They ask for permission. Defer to authority.

They begin their plea by first establishing that their family is politically unproblematic:

“Our father died in the wilderness. He was not one of the faction, Korah’s faction, that banded together against God, but died for his own sin.

We weren't part of the attempted coup. We're not like those radicals, looking to unseat the entire order, here.

We're nice, respectable. We're just looking for this one tiny thing. We respect your leadership and authority.

I think people miss the importance of this allegiance move, sometimes; that it might speak to their awareness of how radical an ask this is. Would they have needed to make this point if they were just coming in for a basic ox goring dispute?

Let not our father’s name be lost to his clan just because he had no son! Give us a holding among our father’s kinsmen!

They're requesting a significant change to inheritance laws– for women to be permitted to inherit at all! Land!!?

But look at how they phrase it.

They make their request, which undermines the strength of patriarchy, by appealing to patriarchy.

The reason that these women should inherit, they tell Moses, Eleazar the priest, the chieftains, and the whole assembly– remember, we're in front of everybody, here– is so that their "father's name [is] not lost."

Marginalized people working in oppressive systems do this all the time.

It's a survival technique. A strategy.

"Here's how implementing better DEI programs can boost our retention."

"Here are all the ways that offering this disability accommodation could benefit your nondisabled members as well!"

And here we see that Mahlah, Noah, Hoglah, Milcah, and Tirzah know how the game must be played to get the thing done.

Which doesn't mean that their feelings about their father weren't also genuine. Just as implementing DEI measures has been proven to lead to better employee retention, and the Curb Cut Effect is, indeed, real.

But there are many ways to word a thing–and it's notable how these women chose to make their case, in public, before everyone.

In fact, it is their choice of this precise tactic– their clear deference to the rules of patriarchy– that wins them approval from the Rabbis in the Talmud:

That [the daughters of Tzlofchad] are interpreters of verses/darshaniyot can be seen from the fact that they were saying: If our father had had a son, we would not have spoken; but because he had no son, we are filling the role of the heir. (Talmud Bava Batra 119b)

Interestingly, other Rabbinic texts grasp the egalitarian argument at the heart of their claim:

When the daughters of Tzlofchad heard that the land was to be apportioned to the [men of the] tribes and not to women, they gathered together to take counsel, saying... God's mercies are for [all genders equally!] God's mercies are for all! As it is written (Psalms 145:9) "God is good to all, and God's mercies are upon all of God's creations." (Sifrei Bamidbar 133:1)

Regardless, some things are clear:

The strategies used by the midwives, by Yocheved, Miriam, or Pharaoh's daughter wouldn't have been effective here.

There's no version of the story in which Mahlah, Noah, Hoglah, Milcah, and Tirzah would have been able to have access to any future land holdings to which their father would have been entitled without the approval of those in power.

(We'll revisit the whole "settling the Land"/Conquest Narrative business soon, don't worry. Let's just put a pin in that for now.)

Different tactics serve us in different contexts.

Sometimes we are dealing with a Pharaoh who doesn’t care what we think, and sometimes with a government that will, at the very least, hear our petition.

And indeed, their request does get sent up the org chart:

Moses brought their case before God.

And God said to Moses,

“The plea of Tzlofchad's daughters is just: you should give them a hereditary holding among their father’s kinsmen; transfer their father’s share to them. (Numbers 27:5-7)

God not only approves their request, but directs it to be given as a "hereditary" holding for their descendants.

And even more than that! Their case is regarded as precedent for systemic change.

On the other side of freedom, after crossing the Red Sea and everything that followed, the Israelites had to figure out how to create a just society — and even then, it was a work in progress.

For, God continues in God's instructions to Moses:

“Further, speak to the Israelite people as follows: ‘If a man dies without leaving a son, you shall transfer his property to his daughter. If he has no daughter, you shall assign his property to his brothers. If he has no brothers, you shall assign his property to his father’s brothers. If his father had no brothers, you shall assign his property to his nearest relative in his own clan, who shall inherit it.’ (Numbers 27:8-10)

This isn't just an exception made for one family, but rather a new procedure that applies to everybody.

Of course, it's not a radical undoing of patriarchy entirely– daughters don't have equal access to sons, and we return to the usual lines of male succession in the absence of daughters– but it gives significantly more female children a crack at their family holdings. It matters.

This is incremental change inside a system.

It doesn't fix everything, but it makes this one thing better, and for that, Senators Mahlah, Noah, Hoglah, Milcah, and Tirzah showed up bravely, asked for more than what they were considered to be entitled, and got something done.

We must give them their flowers for this. 💐 💐 💐

But does the story end with women expanding their rights?

No, of course it doesn't.

There is, inevitably: The backlash, the whining, and the concerns about how this will impact the larger patriarchal systems– since, of course, women's land holdings transfer to their husbands’ line.

So, yeah, we come to Numbers 36:

The family heads in the clan of the descendants of Gilead son of Machir son of Manasseh, one of the Josephite clans, came forward and appealed to Moses and the chieftains, family heads of the Israelites. They said, “... If [Mahlah, Noah, Hoglah, Milcah, and/or Tirzah] become the wives of people from another Israelite tribe, their share [of land] will be cut off from our ancestral portion and be added to the portion of the tribe into which they marry; thus our [tribe's] allotted portion will be diminished...

So Moses, at God's bidding, instructed the Israelites, saying: “The plea of the Josephite tribe is just. This is what God has commanded concerning the daughters of Tzlofchad: They may become the wives of anyone they wish, provided they marry into a clan of their father’s tribe. No inheritance of the Israelites may pass over from one tribe to another, but the Israelite [heirs]—each of them—must remain bound to the ancestral portion of their tribe.

Every daughter among the Israelite tribes who inherits a share must become the wife of someone from a clan of her father’s tribe, in order that every Israelite [heir] may keep an ancestral share. (Numbers 36:1-8, condensed)

Men from the same tribe as the Daughters Tz come to Moses and say: But when they marry, some of the land allotted to our tribe will go off to some other tribe!

And though there are legitimate questions (minus this) about balancing familial and communal priorities, the Torah... well, it makes choices. For, as Dr. David Bernat put it,

Moses could have legislated that if a woman who has inherited marries outside the tribe, the landholding they carry does not pass to the husband or his family.

Instead, they rule that she can't marry anyone outside her own tribe.

Bernat continues:

I am confident that this [alternate] remedy was not proposed because it would chip away at a husband’s prerogative and more broadly, the institutional patriarchy. Instead, the text protects Land Tenure by restricting, in this case, a woman’s conjugal freedom.

The bill got a rider.

Might this be a moment to bring in one of my formative teachers to this conversation?

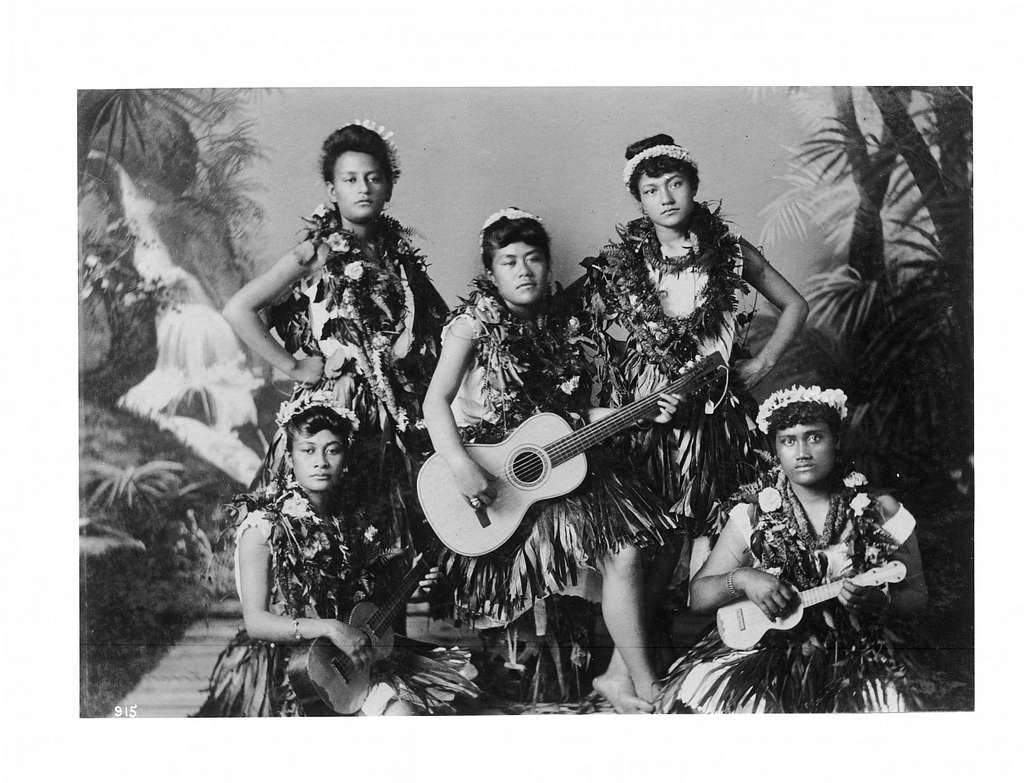

For the master's tools will never dismantle the master's house. They may allow us temporarily to beat him at his own game, but they will never enable us to bring about genuine change. (Audre Lorde, The Master's Tools Will Never Dismantle The Master's House)

Is true institutional change possible? If so, how, to what extent?

Lorde wrote "The Master's Tools Will Never Dismantle The Master's House" as a rebuke to the white women (2) who were still planning conferences on the concept that "the personal is political" without significant input from BIPOC feminists, LGBTQIA feminists and/or those struggling to get by. For, she wrote,

What does it mean when the tools of a racist patriarchy are used to examine the fruits of that same patriarchy? It means that only the most narrow parameters of change are possible and allowable.

When we try to make foundational change without critically engaging with what brought us to this moment in the first place? We will, at best, tweak the same oppressive systems while continuing to run roughshod over those who have been marginalized, disenfranchised, harmed, disempowered up until this point.

I wonder if her Torah (if you will) might be the way out of this wilderness as well.

For, Lorde continues,

Interdependency... is the way to a freedom which allows the I to be, not in order to be used, but in order to be creative. This is a difference between the passive be and the active being... Only within that interdependency of difference strengths, acknowledged and equal, can the power to seek new ways of being in the world generate, as well as the courage and sustenance to act where there are no charters.

No longer to be used, but to be creative.

Lorde demands that her colleagues stop tokenizing, that they begin to embrace the wisdom and creative insights of Black and Brown and queer and older and struggling feminists because it will result in liberatory change forward for everyone– even if (or especially because!) it might involve some changes to, well... the status quo.

No longer to be used, but to be creative.

Radically expanding the perimeters of an institution.

Redefining what it is, looks like, contains.

In fact, one classical midrash on Numbers 27 points us in this direction.

The midrash is discussing the larger context of Moses needing to bring Mahlah, Noah, Hoglah, Milcah, and Tirzah's request to God for clarification, rather than knowing how to rule on it himself. In it, Moses is told:

אָמַר לוֹ הַקָּדוֹשׁ בָּרוּךְ הוּא ... הַדִּין שֶׁאֵין אַתָּה יוֹדֵעַ הַנָּשִׁים דָּנִין אוֹתוֹ.

"The Holy One said: The law that you don't know, women rule on it"(Midrash Numbers Rabbah 21:12)

In other words, there are limits to the knowledge that even God's Chosen Prophet, the man known to speak to the divine face to face, is able to access. And who has that knowledge?

The people locked out of the traditional systems of power.

Any world that fails to celebrate and embrace all that each of us has to offer– from the uniqueness of our vantage– is a world incomplete.

A world that can never be whole.

We must build a new house together.

Using all of our collective wisdom. All of the laws, if you will, that haven't been fully recognized, embraced.

In The Creation of Patriarchy, Lerner writes,

The system of patriarchy is a historic construct; it has a beginning; it will have an end. Its time seems to have nearly run its course—it no longer serves the needs of [people] and in its inextricable linkage to militarism, hierarchy, and racism it threatens the very existence of life on earth.

What will come after, what kind of structure will be the foundation for alternate forms of social organization we cannot yet know. We are living in an age of unprecedented transformation. We are in the process of becoming....

As long as [most people] regard the subordination of half the human race to the other as “natural,” it is impossible to envision a society in which differences do not connote either dominance or subordination. A feminist worldview will enable [people] to free their minds from patriarchal thought and practice and at last to build a new world free of dominance and hierarchy, a world that is truly human.

We say that we receive the Torah in every generation anew, and perhaps it is the process of coming into this freedom that lives in this tension we hold on the precipice of the Promised Land.

The ten truly heroic women bookending the Exodus story teach us that we must have a range of tools to fight for justice at our disposal, that what we do and how we do it depend both on the situation and on each of our individual capacities and talents.

We see the transcendent bravery, and strategy, involved in Mahlah, Noah, Hoglah, Milcah, and Tirzah's request– how stepping forward into what they knew to be justly theirs engendered a change of law given on Sinai.

And, in their verses, we are reminded of the limits of any approach that does not celebrate each of us in our fullness, created in the divine image.

May the Daughters Z show us all the way home.

🌱🌱🌱🌱🌱🌱🌱🌱🌱🌱🌱🌱🌱🌱🌱🌱🌱🌱🌱🌱🌱🌱🌱🌱🌱

Like this? Get more of it in your inbox every week. 🌱

For free every Monday—sign up at the ‘Subscribe now’ button just below.

And if you become a paid subscriber, that's how you can get tools for deeper transformation, a community for doing the work, and support the labor that makes these Monday essays happen.

A note on the subscription model:

I want my work to be as accessible to as many people as possible, in as many ways as possible. That's why the Monday essays are free, and why we donate subscriptions to anyone for whom paying is a barrier to the House of Study posts.

I also believe people should be paid fairly for their work. Needless to say, these two values sometimes seem to be in conflict, but I do what I can to find a fair balance. I offer many resources for free, and charge for others. When you donate generously or pay at the top of our scale, that helps support the work I do, provides access for those who have fewer resources, pays for the infrastructure and the technical and practical support that it takes to do this, and helps us keep the work sustainable.

And as always, if you want in to the Thursday space but paying isn't for you now, just email support@lifeisasacredtext.com and we'll hook you up.

And if you’d like to underwrite one of these donated subscriptions, you can do so by signing up at one of the higher subscription points.

And if it resonated with you, please share this post.

Sending a big pile of blessings and goodness your way. 💕

FOOTNOTES

(1) The excessive transliterations of this name (צְלפְחָד) drive me up the wall. It's not that hard to say. Tzlof is one syllable, and then the second syllable is chad, with the ch being a guttural sound that doesn't exist in English– like challah or hummus. Or Van Gogh or Bach, if you must. (Never mind that there are a number of different places in the throat that one might make different guttural sounds– they're not necessarily all the same in the languages that use them– but that's a whole other conversation.) Anyway. Tzlofchad.

(2) So many of Lorde's speeches and essays were, by necessity, exactly this: having to explain things to white feminists. She did so brilliantly, world-changingly, and–as the Black bisexual author Roxane Gay puts it,

"Forty years later, such meager representation is still an issue in many supposedly feminist and inclusive spaces. The essay ["The Master's Tools..."] is pointed, identifying pernicious issues marginalized people face in certain oppressive spaces—having to be the sole representative of their subject position, having to use their intellectual and emotional labor to address oppression instead of any of their other intellectual interests as if the marginalized are equipped to talk about only their marginalization."

So yeah, plus ça change. Those of us who are white especially should read these Lorde essays as though she was speaking to us, because she was. And everyone: if you have never read "The Uses of Anger" before, please do so today.