easier to ask for forgiveness...?

Penitential Prayers and A Family Legacy, Revitalized

This is Life as a Sacred Text 🌱, an everybody-celebrating, justice-centered voyage into ancient stories that can illuminate our own lives. It‘s run on a nonprofit, so it’s 100% NAZI FREE. More about the project here, and to subscribe, go here:

I wanted to bring you a cool thing, but let's set it up with context, first.

Slichot – literally, "forgivenesses" – are penitential prayers said before Rosh Hashana, which isn't just the Jewish New Year, but is also known as Yom HaDin, the day of judging (uh, translating to take away those end-time connotations, because Rosh Hashana is more about a lil' checkin with God in the lead-up to Yom Kippur, but is nonetheless quite serious business– "on Rosh Hashana it is written, on Yom Kippur it is sealed," cries the liturgy.)

Sephardi and Mizrahi Jews traditionally recite Slichot from the beginning of the month of Elul, the month preceding Rosh Hashana (aka the month we're in now) so that the full month of Elul + the ten days between Rosh Hashana and Yom Kippur = 40 days, like the time Moses spent on Mount Sinai. We Ashkenazi Jews are more slackers in the Slichot department, and don't begin saying them until the Saturday night before Rosh Hashana.

According to Kabbalah, the correct time to say Slichot are at the very end of the night, right before it's properly morning, because this is a time for particular intimacy with the divine– so they're usually they're said first thing in the morning, before regular morning prayers. But over the years it's become a thing in the Ashkenazi world to do the first round late at night.

The core of Slichot is the bit in Exodus 34, where Moses begs God to show him God's face, and God says: Uh, no, but hang out in the cleft of the rock over here and I'll pass by– and God does, and God proclaims something that then becomes a core part of the High Holy Day liturgy, known as the Thirteen Attributes of Mercy. Bold is from Torah, Roman here is from the liturgy, added in later:

וַיַּעֲבֹר יְהֹוָה עַל פָּנָיו וַיִּקְרָא: ה׳ ה׳ אֵל רַחוּם וְחַנּוּן, אֶרֶךְ אַפַּיִם וְרַב חֶסֶד וֶאֱמֶת: נֹצֵר חֶסֶד לָאֲלָפִים נֹשֵׂא עָוֹן וָפֶשַׁע וְחַטָּאָה, וְנַקֵּה: וְסָלַחְתָּ לַעֲוֹנֵנוּ וּלְחַטָּאתֵנוּ וּנְחַלְתָּנוּ:

God passed before [Moses] and proclaimed:

“God, God, a deity, compassionate and gracious, slow to anger, abounding in kindness and faithfulness, extending kindness for thousands of generations, forgiving iniquity, transgression, and sin; and granting pardon.“

And pardon our iniquity and our sin, and take us for Your inheritance.”

For, the Talmud teaches:

“God, God” and it should be understood as follows: I am God before a person sins, and I am God after a person sins and performs repentance, as God does not recall for a person their first sins, since God is always “God, merciful and gracious” (Exodus 34:6). (Talmud Rosh Hashana 17b)

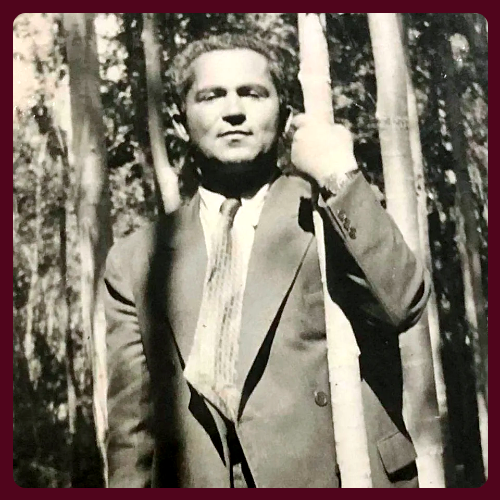

Galeet Dardashti was raised by an Ashkenazi mother and an Iranian Jewish father who immigrated to the US as a teen and then became an Ashkenazi-style cantor. They were a musical family– she was on stage singing harmony with one of her sisters by the time she was three. Throughout her childhood, she performed with her parents and her two sisters– Danielle and the now-rabbi Michelle–as “The Dardashti Family” or “A Dash of Dardashti.” But, as she says, "we didn’t perform Persian music."

She did hear her grandfather Younes singing it, though, and as she got older, she becamemore interested in her heritage, both personally and professionally– especially given the fact that her grandfather had been an acclaimed singer.

Here, a little conversation with Galeet about how the process of recovering her roots led to finding, and creating, a profound Slichot gem.

What was your grandfather’s life in Iran, and then after he immigrated?

In Iran, he was a radio star beloved among the mainstream Muslim population. When he immigrated to Israel in 1967 he didn’t have an audience for his music. But for more than a decade he was able to travel back and forth between Israel and Iran for performances. It was a short flight so it was almost like commuting for work. It’s hard to imagine the close relationship Israel and Iran had back then. But after the Islamic Revolution in 1979 he couldn’t return to Iran again. I’m sure this was devastating for him. I don’t think he ever thought he wouldn’t be able to return to his country and audience.

How did your family manage to keep recordings of him through many stages of immigration?

Danielle and I started working on the The Nightingale of Iran podcast [about our quest to understand why our family left Iran at the height of their fame as singers in the larger Iranian society], and while Danielle was staying at my parents’ house during a home renovation, she made an incredible discovery: a motherlode of recordings that my family made for one another between Iran, New York, and Israel between 1959-1980s!

Long distance phone calls were so expensive, especially in those early days, so the family would record hours-long voice memos telling each other what was going on and–because we are a musical family–singing for each other. These recordings range from telling each other about mundane things to recording full Passover seders in Iran and New York for each other. And NO, we didn’t know this stuff was always there. We were totally shocked to find it–and especially to find it in perfect condition. My parents had forgotten that it was there.

How did those tapes lead to this shared album?

So my famous grandfather sang Persian classical music in Iran but since he was also Jewish, members of his community would often ask him to lead services. There is no profession of cantor there, so those who know the liturgy and have beautiful voices are often asked to lead. My saba [grandfather] led services often and he was particularly known for his incredible renditions of the prayers of Selihot. In Iran and most of the Middle East, Jews chanted these prayers in the late night or early morning for an entire month before Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur and Jewish Iranians in Tehran would flock to hear when my grandfather led these prayers.

I found these moving recordings of my saba singing the prayers of Selihot in Iran and that’s how Monajat–my Persian musical reinvention of Selihot–came about. I don’t speak Persian well but I deeply connected with these recordings of him singing in Hebrew. I began sampling his voice and composed music around him so I could duet with him. It was a powerful way for me to feel my saba’s presence–even though he passed away 30 years ago. Though the Iranian Revolution largely erased my grandfather’s name in Iran, I’m honored to bring his incredible voice to the world again.

October 11th-12th, New York, NY, Kanisse, Galeet Co-leads Egalitarian Sephardi/Mizrahi Yom Kippur services

What does “Monajat” mean?

“Monajat” is a Persian word that describes an intimate conversation with God. My Saba’s recording of Selichot ends with a powerful poem he called “Monajat,” which he chants in Persian — as opposed to in Hebrew, the language of the other Jewish prayers in Selichot. Nobody in my family knew where this poem, “Monajat,” came from — it was just a piece with which my grandfather ended Selichot when he led services — his unique thing. It was written in the style of the 13th century Sufi poet Rumi, and urges listeners to shake off their slumber and offer praise to God. We now think that my grandfather wrote this text himself and then musically interpreted it as he would interpret a Rumi or Hafez poem.... Prayer has always been both cultural expression and artistic creation.

For me, it beautifully represents how my grandfather was both so Persian and so Jewish simultaneously, and there was no distinction or separation between those identities. For him, singing “Monajat" in Persian at the end of his prayers seemed totally natural. So emphasizing the shared culture of Muslims and Jews is a very important goal with Monajat — particularly at this horribly depressing time in Israel/Palestine and in the world where it feels like these clear divisions always existed.

Monajat (Intimate Dialogue with the Divine)

Excerpt from a Persian poem attributed to Younes Dardashti

Chanted by Younes Dardashti; synth effects: Shanir Blumenkranz; translation by Ruby Namdar, Shahrokh Bassal, and Hazzan Farid Dardashti

Let me open, in the great name of God:

O heart, rise and make yourself humble

For nothing in this world is higher than humility,

And humility belongs to those who are early risers.

The heart says: "Rise and shine!"

But the evil inclination whispers: "In a moment..."

Shake off the evil inclination and get out of bed!

It is time to offer The Almighty your praises.

Every morning, at dawn, the roosters crow in prayer.

How would you know it if you were still asleep?

Only those who are awake know this secret.

O Lord, if I ever may be found worthy,

Let a sleepless night be the reward for my righteousness.

The hour to approach your gate with words of supplication has arrived.

🪬Questions for Discussion:

- What do you think is the purpose of asking for forgiveness of the divine again and again and again in the days leading up to Rosh Hashana?

- Why do you think the Thirteen Attributes of Mercy is at the center of this process?

- What doesn't Slichot do?

- In what ways is the process of Galeet's recovering these archived tapes and turning them into new art an apt metaphor for the tshuvah– return, repentance, repair– process? In what ways is it limited?

- What is the poem "Monajat," about? On the literal level? On a more metaphoric level?

- What does shaking off sleeplessness look like in your life? What's hard about it? What does it look like to do this? What happens when you do so?

🌱🌱🌱🌱🌱🌱🌱🌱🌱🌱🌱🌱🌱🌱🌱🌱🌱🌱🌱🌱🌱🌱🌱🌱🌱

Like this? Get more of it in your inbox every week. 🌱

For free every Monday—sign up at the ‘Subscribe now’ button just below.

And if you become a paid subscriber, that's how you can get tools for deeper transformation, a community for doing the work, and support the labor that makes these Monday essays happen.

A note on the subscription model:

I want my work to be as accessible to as many people as possible, in as many ways as possible. That's why the Monday essays are free, and why we donate subscriptions to anyone for whom paying is a barrier to the House of Study posts.

I also believe people should be paid fairly for their work. Needless to say, these two values sometimes seem to be in conflict, but I do what I can to find a fair balance. I offer many resources for free, and charge for others. When you donate generously or pay at the top of our scale, that helps support the work I do, provides access for those who have fewer resources, pays for the infrastructure and the technical and practical support that it takes to do this, and helps us keep the work sustainable.

And as always, if you want in to the Thursday space but paying isn't for you now, just email support@lifeisasacredtext.com and we'll hook you up.

And if you’d like to underwrite one of these donated subscriptions, you can do so by signing up at one of the higher subscription points.

And if it resonated with you, please share this post.

Sending a big pile of blessings and goodness your way. 💕