Guest Post: S. Bear Bergman is feeling... inclined

On the yetzers -- the good and evil inclinations in Judaism

This is Life as a Sacred Text 🌱, an everybody-celebrating, justice-centered voyage into ancient stories that can illuminate our own lives. It‘s run on a nonprofit, so it’s 100% NAZI FREE. More about the project here, and to subscribe, go here:

First of all, I wanted to follow up on last week's post. I knew it would spark a lot of feelings, and it has. Much of the feedback has been positive, but unsurprisingly, some has been from folks who are frustrated that I didn't bring in– well, any number of elements of the larger historical story, of which there are many. A few times within the piece itself I tried to name that it was impossible to hit all the dimensions of the story, but it's also quite possible that I did not communicate effectively, so I'd like to underscore the points I was trying to make over there, in case you were a reader feeling this frustration but did not reach out to share that with me directly:

The piece was never meant to be a comprehensive tour of all the aspects of either of the histories of the US or Israel, nor a detailed accounting of all culpabilities in every direction– or even an observation of every empire that has engaged in either place. Rather, I was attempting to note that

a) Some preconceived ideas that some folks have about Those Powerful Jews Turning The Screws of History (tm) are a lil' misplaced

b) While there are also plenty of differences and nuances between those two stories, there are also some interesting patterns viz Jews and Empire and state power that are worth observing and discussing

c) No matter what other actors or factors might be present, we must keep our side of the street clean– to take responsibility for what is ours to own, to repair what is ours to repair, to do the work that is ours to do. Elul (or, any time, I'd argue) isn't exactly the time to be huffing, "I don't want to talk about my responsibility to others until we talk about what's owed me." Pretty sure that's not what the point of any of this is, y'all.

So that's what I want to say about that.

Now, to the fun stuff:

I've been a fan of S. Bear Bergman's work for, gosh, decades now. From his essay collections to his theater work (sörry, he's in Canada now: theatre work), from starting up a micropress to publish #ownvoices feminist, racially-diverse, 2SLGBTQ+ positive children’s books to, as you'll see below, his irresistible style of advice-giving– it seems that everything he does just oozes brains, heart, soul and menshkeit.

So when his most recent book, an illustrated advice compendium for parents, on the work of parenting, had this delightful section on the yetzer hatov and the yetzer hara– the good and evil inclinations, as my tradition calls them– I thought it might be fun to share with you all. They are important all year long, but particularly apt to consider during this Jewy season, as we think about what kinds of choices we have made this past year and what kinds of choices we want to make in the future– what kinds of people we would like to choose to be, to become.

This lil' graphic essay talks about these concepts in the context of raising kids, but, as should be clear, everything he talks about is really about the complicated work of being a person, which, for better or worse, we all have to do. (The prequel to this book– Special Topics in Being a Human– is explicitly about, well, that.)

If you are or love a parent, needless to say, this is great, great stuff. All of it. And! You can use the discount code BERGMAN30 to take 30% off any of his books until the end of October at the Arsenal Pulp Press website.

Turning the mic over to Bear:

The Yetzer Hatov and the Yetzer Hara

By S. Bear Bergman

The work of advice-giving - which I love - is complex, in many ways (which is part of why I love it so much). There are many balances to strike: how to write in a way that feels knowledgeable but not judgmental, how to take context and identity into account without accounting for so many possibilities that the advice is so vague it’s useless, how to discern what in my own life is a considered method that supports my values and what is just… my opinion (this is how I ended up writing a parenting book in which a quarter of the chapter headings are “Strong Opinions”). Parenting is a lot of work, and a fair bit of that work is in making decisions: what do I or we want to have happen? How am I or we going to accomplish this? It starts well before a child arrives to a family and carries on… indefinitely, to be honest, though the window of influence is for sure open wider at some stages than others.

Among the things I noticed, as a parent, and wanted to address were the occasions I mentioned or introduced my children and the new person would ask me, “Are they good?”

Or sometimes they would ask the child: “Are you a good girl/a good boy?”[[1]] My response was instinctive the first time and now feels like a statement on my entire orientation to parenting (and life, honestly):

I refute the entire premise.

“Goodness” as measured by obedience is - in my opinion - a terrible way to talk about people regardless of age or success in remembering that we don’t gnaw our crayons, and heavily influenced by the lens of white supremacy and its idea that people must be “good” (and compliant) in order to be worthy of inclusion, or protection, or assistance and that some people are necessarily therefore “bad” and unworthy of those offices of safety and support.

In fact, we’re all everything, all the time.

That is the way people work. We are all, always, both worthy and responsible for continuing to improve. We are all “good” and all “bad,” all thoughtful and thoughtless, all responsible and heedless, all attentive and all distracted, and on and on. That’s the nature of humans.

(For the record, when people ask me if one of my children is “good,” my stock response is to say “They’re perfect in every way,” which I believe is true.)

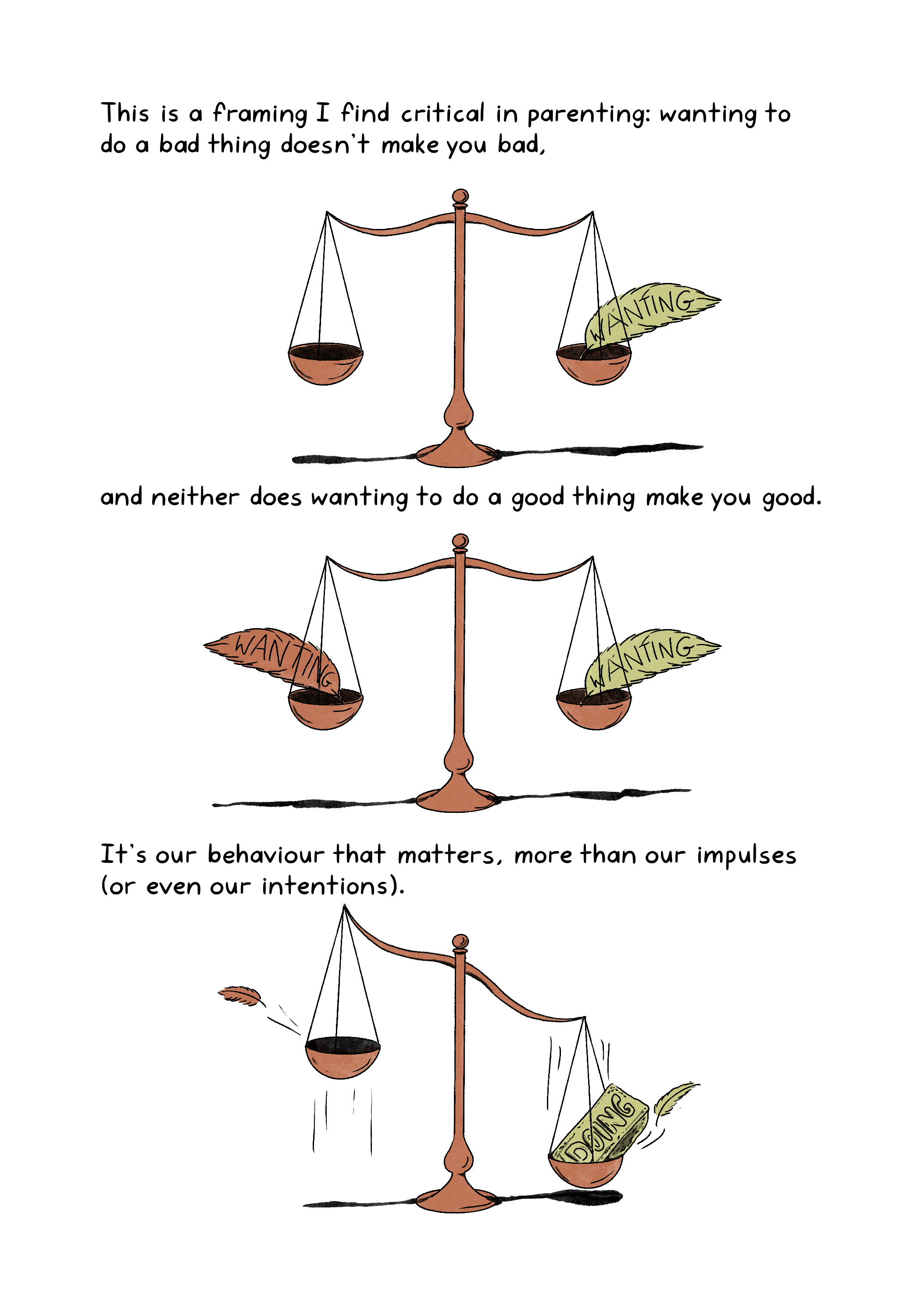

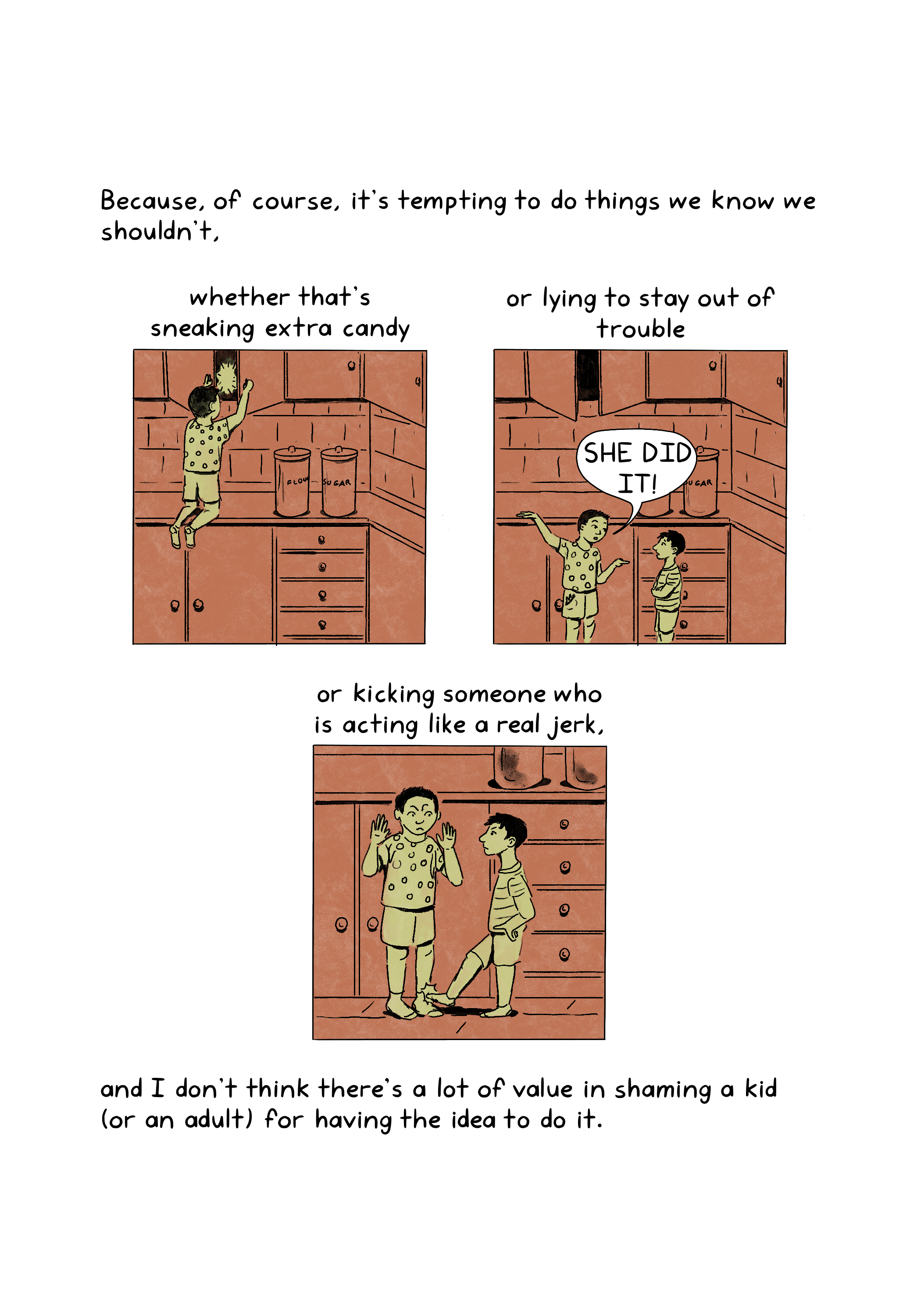

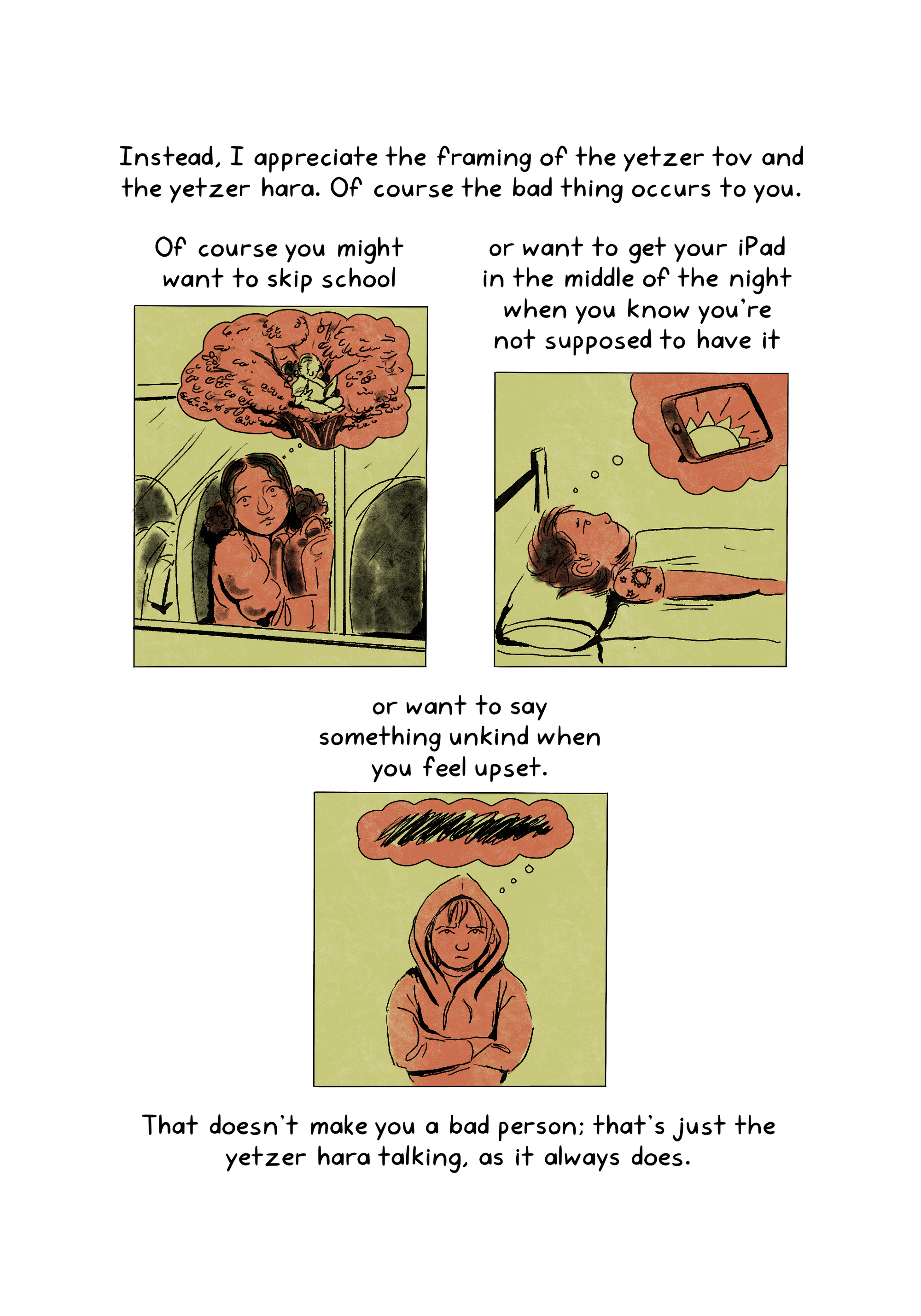

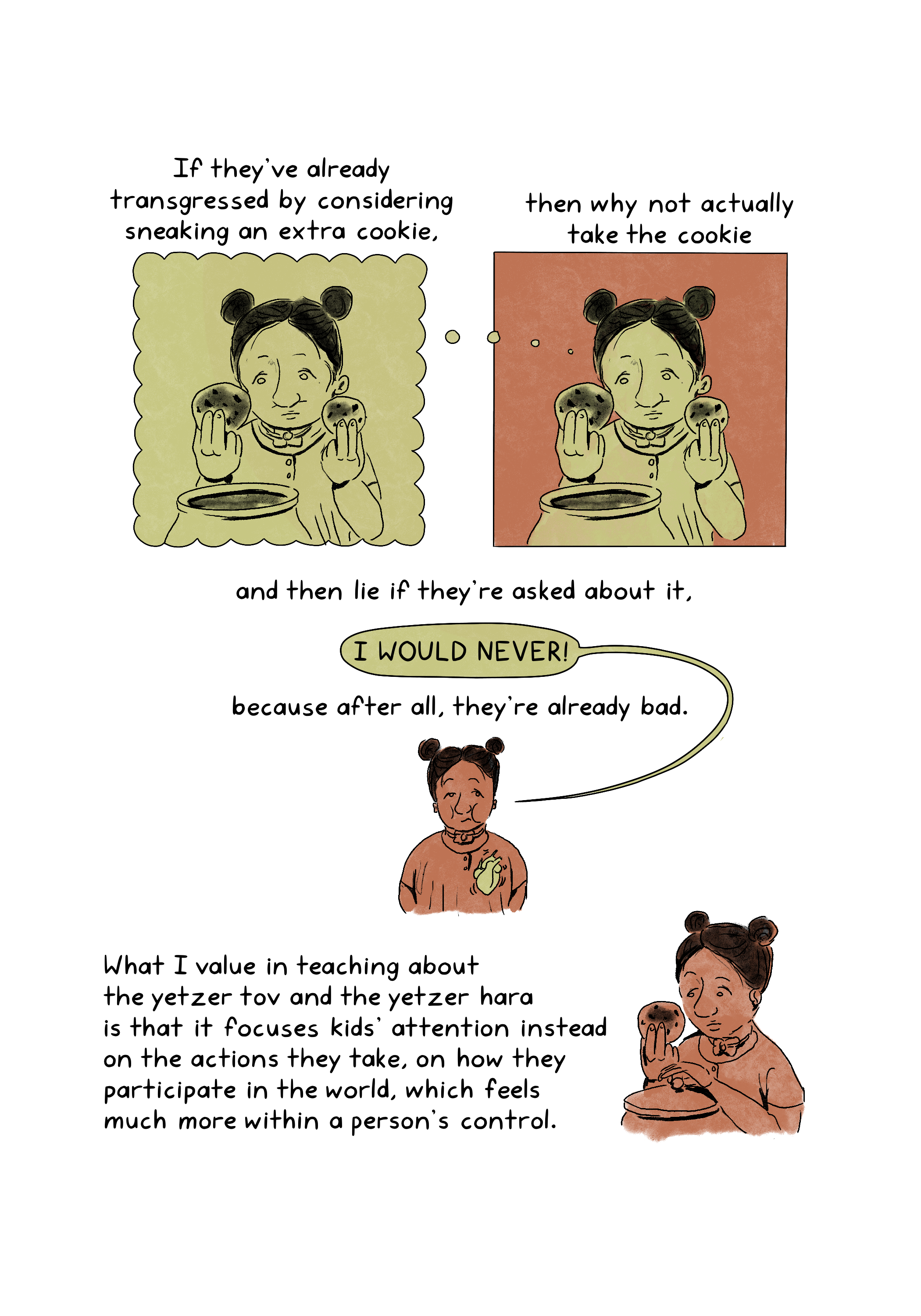

In thinking about all these kinds of balance, all this talk of “good” and “bad”, I was moved to include a chapter about the yetzer hatov and the yetzer hara, a concept that I have found incredibly helpful as a person as much as a parent - the idea that it is expected, human, and perhaps even necessary to have a thought or idea we should not act upon; that having a bad thought does not make us bad people (and that sometimes, it can lead us to a righteous action). Also, correspondingly, that having a good thought also does not necessarily lead us to a righteous action.

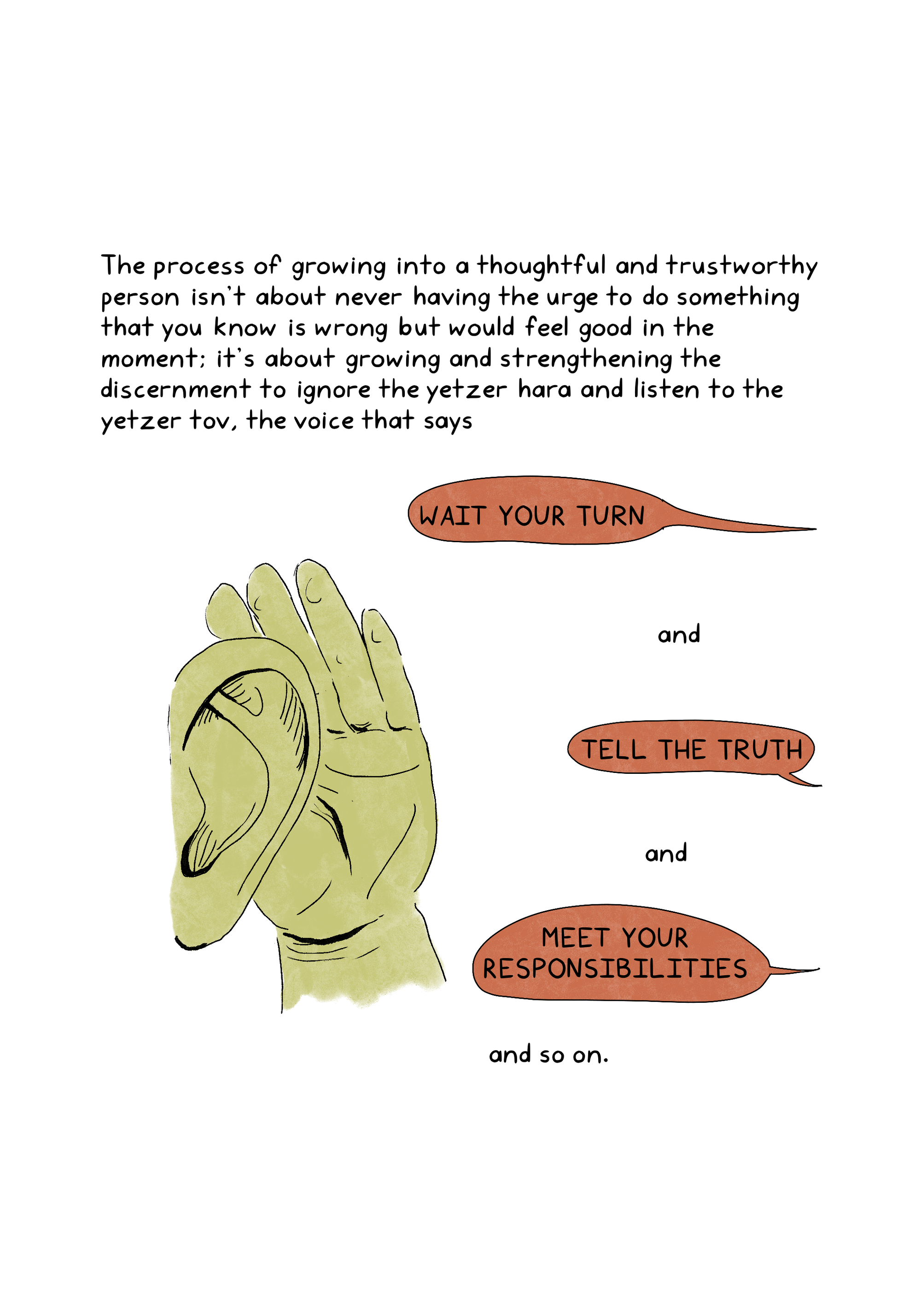

The work of becoming an adult is in learning to discern which inclination is speaking and how much heed we should accord it.

I found it an incredible relief as a younger person to know that having an idea or impulse to do something “bad” didn’t make me a bad person.

It was even more of a relief to read these two texts– this Mishnah, commenting on Deuteronomy 6:5 (bold is original text, Roman adds context for comprehension):

One is obligated to recite a blessing for the bad that befalls them just as they recite a blessing for the good that befalls them, as it is stated: “And you shall love God your God with all your heart, with all your soul, and with all your might” (Deuteronomy 6:5). “With all your heart” means with your two inclinations, with your good inclination and your evil inclination, both of which must be subjugated to the love of God. (Mishnah Brachot 9:5)

and this Midrash:

Rabbi Naḥman bar Shmuel bar Naḥman said in the name of Rav Shmuel bar Naḥman: “Behold it was very good” (Genesis 1:31) – this is the good inclination; “and behold it was very good” (Genesis 1:31)– this is the evil inclination. Is the evil inclination, then, very good? This is a rhetorical question. Rather, were it not for the evil inclination, a person would never build a house, would never get married, would never beget children, and would never engage in commerce. (Midrash Genesis Rabbah 9:7)

With these two texts together, I see that I am responsible for what I do– for which inclination I follow– and I am also responsible for developing the understanding to see that a “bad” inclination (like, say, the ego of believing I know enough about parenting to ask other people to consider my ideas as a roadmap) can lead to a “good” result (I hope). From both a place of ego and a desire to be helpful, I would like to offer my chapter on the yetzer hatov and the yetzer hara for your consideration, with the recommendation that I find it an invaluable framing in my life– and I hope you will, too.

May you strengthen your own Yetzer HaTov this year– and remember that your Yetzer HaRa only makes you human. Nothing more, nothing less.

S. Bear Bergman is a storyteller, the author of nine books, and founder of Flamingo Rampant press, which makes feminist, culturally diverse children’s books celebrating 2SLGBTQ+ kids, families, and communities. Bear began his work in equity at the age of 15, as a founding member of the first ever Gay/Straight Alliance, and has continued to help organizations and institutions move further along the pathways to justice ever since. These days Bear spends his time making trans cultural competency interventions however he can (including his wildly successful new show The First Jew In Canada: A Trans Tale) and trying to avoid stepping on his children’s Lego. Learn more at www.sbearbergman.com

Saul Freedman-Lawson is a zine-maker, a camp counsellor, a bookseller at Another Story Bookshop, and the illustrator of Special Topics in Being a Human (Arsenal Pulp Press, 2021). They are also the illustrator of the zine NOT HOME: True Stories From Abandoned Places, by Twoey Gray, and the writer and illustrator of Naturally (Old Growth, 2021). They make art about queerness, transness, Judaism, disability, and childhood, among other things. They like to draw people with big noses and big genders. Learn more at https://www.sfreedmanlawson.com/.

🌱🌱🌱🌱🌱🌱🌱🌱🌱🌱🌱🌱🌱🌱🌱🌱🌱🌱🌱🌱🌱🌱🌱🌱🌱

Like this? Get more of it in your inbox every week. 🌱

For free every Monday—sign up at the ‘Subscribe now’ button just below.

And if you become a paid subscriber, that's how you can get tools for deeper transformation, a community for doing the work, and support the labor that makes these Monday essays happen.

A note on the subscription model:

I want my work to be as accessible to as many people as possible, in as many ways as possible. That's why the Monday essays are free, and why we donate subscriptions to anyone for whom paying is a barrier to the House of Study posts.

I also believe people should be paid fairly for their work. Needless to say, these two values sometimes seem to be in conflict, but I do what I can to find a fair balance. I offer many resources for free, and charge for others. When you donate generously or pay at the top of our scale, that helps support the work I do, provides access for those who have fewer resources, pays for the infrastructure and the technical and practical support that it takes to do this, and helps us keep the work sustainable.

And as always, if you want in to the Thursday space but paying isn't for you now, just email support@lifeisasacredtext.com and we'll hook you up.

And if you’d like to underwrite one of these donated subscriptions, you can do so by signing up at one of the higher subscription points.

And if it resonated with you, please share this post.

Sending a big pile of blessings and goodness your way. 💕

[[1]]: And the gendered nature of it all made it worse! The language of "good boy" and "good girl" really reiterated the idea that the qualities of “good” in a boy would be different from the qualities of “good” in a girl, and that no other genders are tolerated, all of which I was busy parenting in a straight line away from. You can’t imagine someone saying to a preschooler, “Are you a good kid?” and, by that, meaning the same as, “Are you a good boy?” The former is about spirit, and the latter is plainly about obedience. (RDR adds: For more of Bear's gender brilliance, don't sleep on his essay collections: Butch Is a Noun, The Nearest Exit May Be Behind You and, perhaps the tenderest of them all, Blood, Marriage, Wine and Glitter.)