Esther: The Patron, uh, Saint of Crypto-Jewry

honoring the legacies of those living double life

This is Life as a Sacred Text 🌱, an everybody-celebrating, justice-centered voyage into ancient stories that can illuminate our own lives.

It‘s run on a nonprofit, so it’s 100% NAZI FREE. More about the project here, and to subscribe, go here:

Purim's almost here!

(It begins this Thursday night!)

So today we're going to look at a place where that holiday has a particularly strong historical resonance – and that, perhaps, might echo even more this year, as Christian nationalist state repression starts to get a little too close for comfort.

Let's begin with a bit of context, first, shall we?

We've got the Reconquista– the Christian battles to wrest what's now Spain from Muslim rule; by 1248, the Christians controlled everything but the small state of Grenada in the south. (That last bit they got in... January, 1492.)

Anti-Jewish violence, in the wake of incitement, began in earnest in 1391– at which point many Jews became conversos, converted to Catholicism. But some / many tried to be Crypto-Jews: Secret Jews who attempted to maintain their own tradition in secret.

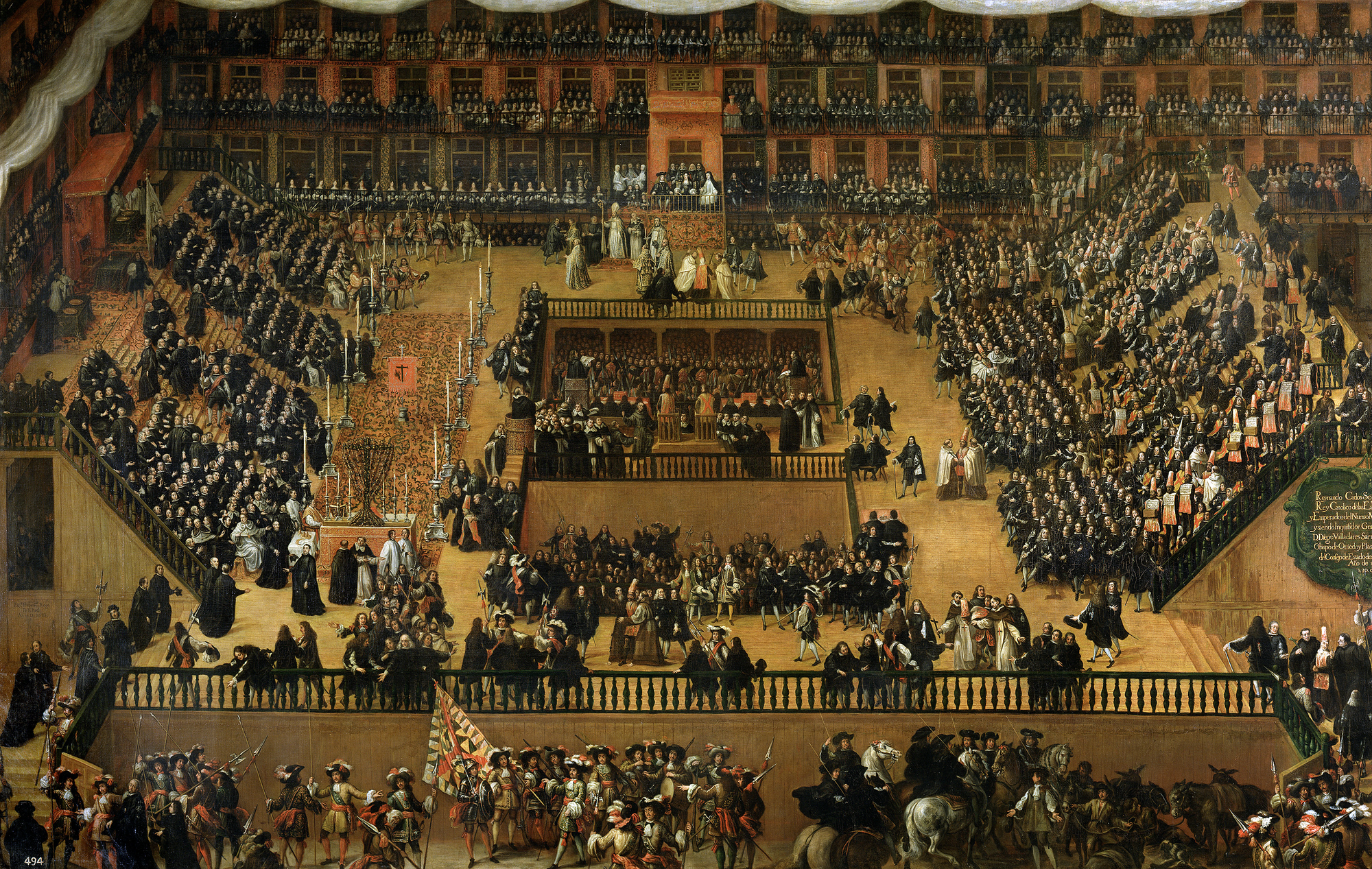

Though there were a number of factors leading to establishment of the Spanish Inquisition in 1478 (yes, yes), the investigation and handling of these conversos in the event that they were practicing Judaism on the down-low was very much a catalyst and main goal.

This was my first impulse, of course it was

Then, in the summer of 1492, the monarchs of Spain, (and, five years later, Portugal), commanded all Jews to either convert or be expelled from the country, leaving behind everything they owned, setting out impoverished on a perilous journey. So even though an estimated 100,000 or more did leave, many more decided to stay and go the Crypto-Jewish route.

Publicly, they appeared to be devout Catholics, but secretly, at home, they observed Shabbat, holy days, and kosher practices the best that they could (without arousing suspicion).

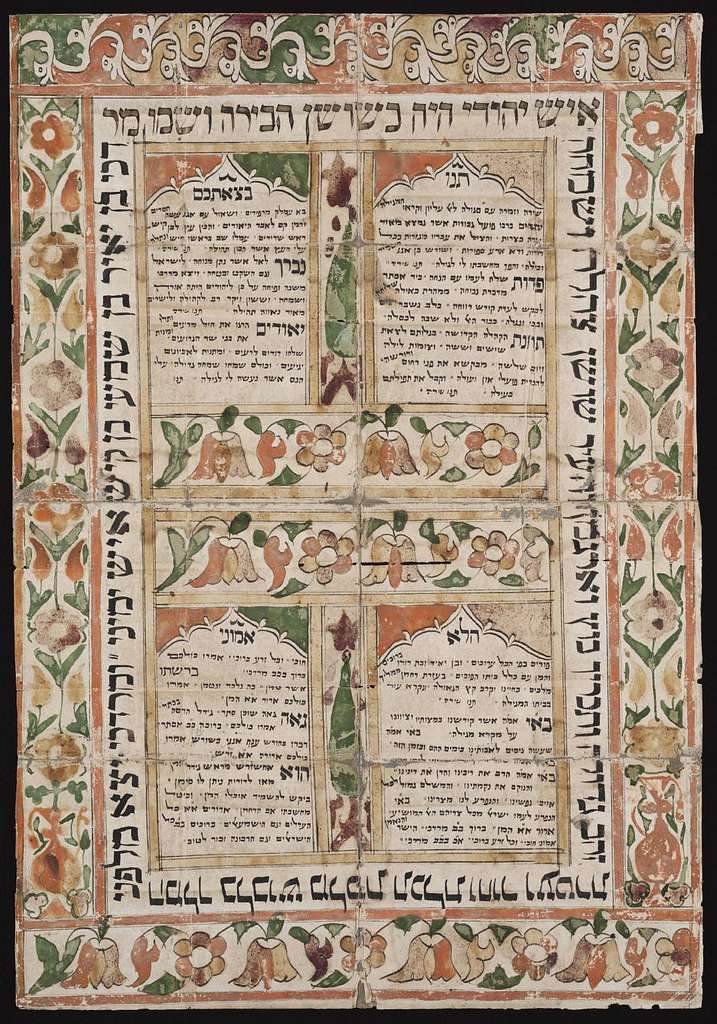

One holiday that was of particular importance to many Crypto-Jews was, yep, Purim– the story of Esther, chosen to be queen from among all the trafficked virgins maidens in the kingdom, but urged by her kin Mordechai to hide her Jewishness from King Ashasverus for her own safety.

(She even changed her name from Hadassah to Esther, and Esther's root word means hidden. And traditions suggested that she found ways to navigate keeping kosher and Shabbat as she could– needless to say, this story resonated for many Crypto-Jews.)

Crypto-Jews observed Purim under the slightly safer name, "Festival de Santa Esterica," (Festival of Saint Esther) and then, eventually in the Southwest and Latin America, "Dia de Ester." (Esther's Day).

As Crypto-Jews moved from Spain to Portugal to the land now called North and South America, visual veneration of Esther became a thing, both in statue and painted icon form. Santa Ester was often portrayed as holding a hanging rope in one hand, and a crown in the other– the death penalty at stake if she is discovered, and the privilege and access that she possesses while in hiding.

The Crypto-Jewish Fast of Saint Esther would typically last for three days at the beginning of Lent (rather than the single Taanit Esther/Fast of Esther the day before Purim in the Jewish community), likely tripled in length because Esther asked her uncle Mordecai and the other Jews of Shushan to fast for the three days leading up to her approaching King Ahasuerus to ask him to spare the Jews (Esther 4:16).

In the Crypto-Jewish world, this was regarded as a special fast for women– some would fast only from sunrise to sunset, and in other families, the women would split the fast between them. (Evidently there was a superstition that a young woman who could fast for all three days would find a good husband (!))

Crypto-Jews, it seems, believed that this fast* could help them atone for their Chrstianizing behavior, but that it was risky in a number of ways– I've read one report of a young woman who died as a result of fasting for all three days, and imagine there may have been others. And just as dangerous: A household employee might tip off the Inquisitors about such behavior if people weren't careful.

*As well as others-- for example, some Crypto-Jews would fast on Mondays and Thursdays, as did Jewish pietiests of days past. And other minor fast days were, in some places, engaged rigorously, as well as, eg. Yom Kippur.People fasting would go to all sorts of lengths to try to keep their actions quiet– going out into the country; pretending not to feel well; sending any household workers out on an errand and greasing up the plates and cutlery to make it look like they'd eaten while the person was away; or even staging a fight right before mealtime– so that the one person runs out in a huff, with others perhaps chasing after them to continue the so-called drama.

Needless to say, people got caught sometimes. For example, the Carvajal family faced the Inquisitors in New Spain (now Mexico) in 1589 and 1595–1596 for their observance of Judaism:

They said doña Isabel upheld the fast in contemplation of the fast of Queen Esther, in all of the said three days she had not even eaten an egg with ash, and on Saturday doña Isabel only did not fast because it was a holiday (Shabbat), and then she began to fast on Sunday at midday like it is said to continue with her fasting…

And in this case, there were also acts of self-flagellation involved. Prof. Emily Colbert Cairns reported that

Isabel and Leonor de Carvajal bled for Esther with hair shirts, coarse garments with bristles that would make the wearer bleed so that they could be physically connected with their faith, they fasted for her, but above all they looked to her for guidance at a time when more and more of their endangered cultural heritage was in their hands.

After the Fast of Saint Esther came the the Feast of Saint Esther.

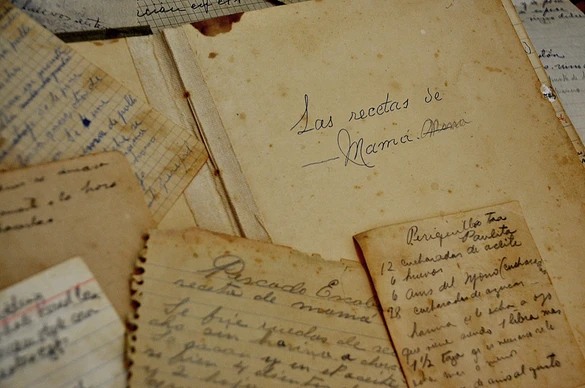

Evidently women lit devotional candles, and mothers would use this time of cooking to teach their daughters ancestral recipes and, potentially (explicitly or implicitly) some of the laws around keeping kosher that might be off the table at other times.

It's possible that some of them might have told, or even read, the story of Esther at that time, as well.

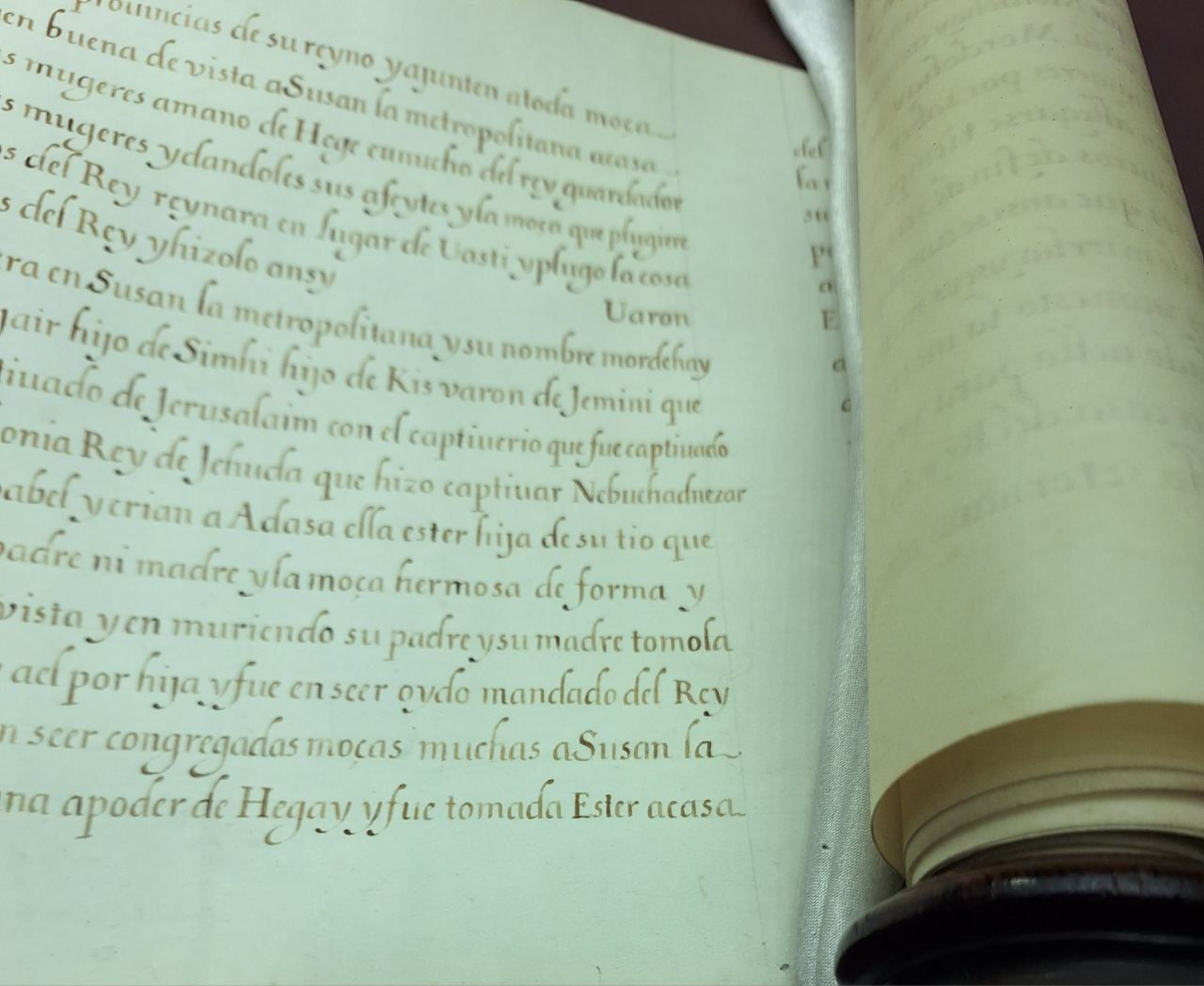

Crypto-Jews living on the island of Majorca, just off the Spanish mainland, were eventually able to get books banned by the Inquisition via traders who traveled to safer Jewish communities. Pedro Onofro Cortés was one such trader.

His niece, Ana Cortés, is on record as eating fish in the evening of the first two days of the Fast of Esther, and celebrating the end of the fast with “garbanzos con espinacas, cazuela de broçats y garvellones”– a chickpea, spinach, and hearts of palm stew.

Some the Crypto-Jews of Sicily had caponata as part of their feast, with eggplant instead of fish. Evidently Spanish Jews were so known to be eggplant stans that even the satirical poetry of the day made note of it. (Needless to say, "food that raised eyebrows with Inquisitors" is a whole other subject– from marzipan to sponge cake, leeks and more.)

Of course, the reason we have the Cortés' chickpea stew recipe on record is that it was reported to Inquisitors; trying to stay Jewish came at a real cost. As writer Ronit Treatman noted,

Pedro Onofro Cortés was burned at the stake. Ana Cortés was sentenced twice for the crime of “Judaizing” or secretly practicing and teaching Judaism, once in 1677 and again in 1688. Ultimately, she was excommunicated, all of her property was impounded, and she was paraded through the streets of Palma de Mallorca in an auto-da-fé, or act of faith, a public ritual of penance.

The Spanish Inquisition was abolished in... 1834. When the Mallorcan Jewish community was finally recognized by the Israeli Rabbinate in 2011,* they noted that Purim was especially significant to these folks. All these hundreds of years later.

*We will save the screed about the Rabbinate and who they do and don't recognize as Jews and what that's about for some other day...

Below is a prayer/poem written by Portuguese Crypto-Jews that was then taken to Brazil, handed down through the generations, that Ronit Treatman translated from Portuguese. As she notes, the reference to St. Michael comes from the Book of Daniel (12:1). It doesn't take much of a leap to guess how Crypto-Jews might have connected with this verse:

“At that time, the great prince, Michael, who stands beside the sons of your people, will appear. It will be a time of trouble, the like of which has never been since the nation came into being. At that time, your people [the Jews] will be rescued, all who are found inscribed in the book." (Daniel 12:1)

The prayer is as follows:

Holy Queen Esther, pray for us!

Our lady of Judah, pray for us!

I come with nothing– no water, no bread. But I offer God this intention:

Lord St Michael praise be to him, here comes the butterfly from our church.

Just as Mordechai was saved, blessed be me too

All hail Queen Esther! Long Live Mordechai! Long live the Jewish people!

Of course, the story inspired art by Crypto-Jews as well– like the play Esther, written by Salomon ben Abraham Usque– who fled the Portuguese Inquisition– was performed in Venice in 1558. João Pinto Delgado was also born in Portugal; his family wound up in Rouen, France, where he published Poema de la Reyna Ester in 1627, dedicating it to the influential Cardinal Richelieu. (Eventually Pinto Delgado landed in Amsterdam, from which he funded Jewish education and wrote fierce attacks on the Inquisition and on the New Christians in Rouen who sold out other people. Safety is nice.)

Here's a description of a more recent New Mexico observance– one that dates at least until the mid-1960s, when a new archbishop arrived in Santa Fe and tried to shut things down, from a 1993 study:

Clemente Carmona remembers that [Dia de Ester] was primarily a women's festival, during which mothers explained domestic tasks to their girl children. They fried empanadas, small pastries filled with beef, pumpkin, or whatever dried, spiced vegetables were left from the winter hoard. Sometimes the triangular pies were referred to as hamantashin ("Haman's hat"). These pies were consumed with much drinking and singing by neighbors dressed up in their new spring clothes. Women lit candles to Saint Esther and other favorite personas, always including the Gran Santo-Moses. The oldest person present for the occasion–man or woman–was asked to say the blessing over the wine.

There are so many stories that sound like Josef García’s. His maternal grandmother

would light two candles every Friday and then move her hands around in a circle, saying words in a mysterious language. When someone died, he said she would cover all the mirrors with black cloth. When he asked her about these traditions, she would say they were “very old family traditions taught to her by her grandmother.”

“In 1982,” García said, “my elderly great uncle told me the reason I was uncomfortable in Christianity was because we were Jews. Suddenly, it made sense to me, my mother shouting about the filth of pork and the other family customs."

Stories like this abound: Women are lighting candles on Friday nights– presumably in honor of the Catholic saints? But it's not clear which ones? And they'd always do shopping and food prep earlier on Friday afternoon, in a rush? Sometimes fathers or grandfathers would come home with fresh bread, often even in the form of braided rolls, obtained somewhere unknown. Daniel Yocum of Atrisco, New Mexico– an enclave of Crypto-Jews– remembered the Friday-night candles in his home, around which "Old Testament" stories would be retold.

Or stories like Genie Milgrom’s: She was raised Catholic first in Cuba and then Miami. But the discovery that the foodways she'd been raised with were Jewish led her to trace back a staggering twenty-two generations (including finding records indicating that 45 of her relatives were burned at the stake for being Jews.)

And armed with a stash of hundreds of recipes, handed down generation to generation, she was even able to figure out their evolution:

"So they went from almonds and figs [in Spain and Portugal] to mangoes and passionfruit in Cuba. The minute that anise liqueur got switched for rum, I knew they were in Cuba."

She has since converted formally and is now an observant Jew. She hosts and cooks for holidays, now, and has published a cookbook with her findings.

I searched #DiaDeEster on Instagram and a few things were immediately apparent: Modern-day observance was still definitely a thing, at least in Brazilian churches, which seemed to account for most, if not all of the posts using that hashtag, at least; as you can see, it looks like women celebrating together, often wearing crowns, is a big part of the day.

Over the centuries, many outwardly Christian Crypto-Jewish families became, well, Christian. Images from contemporary celebrations of Dia de Ester, found on Instagram, all from, if I understand correctly, churches in Brazil. (I reached out to all of these places and more to ask them about their understanding and experience of the holiday, but did not hear back from a single one, to my great regret.) (Six images advertising Dia de Ester events in Portugese with a range of fonts and styles, but all fairly feminine in aesthetic; all but one use either crowns, flowers, or both in their imagery (the last features more of a desert backdrop against a delicate, stylized white font), and most of them employ pinks and purples in some way.)

Brazilian Quechua artist Marte Awqakuq, who does a lot of research into "more obscure" Catholic saints, told me,

There are records of converted Jews bringing the cult to Esther from Portugal, and there are cities named after her. In Mexico, this cult to Esther was more explicit until the '70s and '80s, when the Catholic Church was more emphatic in stopping it. There, it is possible to find material evidence of this cult, with images of the saint. I have the impression that [many] practitioners [in Brazil] hid the cult of her very well, because the Church had already noticed the connection of this saint with Judaism, even in the New World.

Contemporary women in Brazil celebrating Dia De Ester today: Photos of many, many women of various ages, including girls, posing, smiling, wearing headband crowns, costume crowns, flower crowns, sometimes capes and other costume elements, sometimes without costume and brandishing candy, often in crowds posing in selfie mode, sometimes holding gifts, all appearing to be smiling and celebratory.)

Santa Ester's legacy lives on in many important ways. Like cheese.

In the Purim story, we're told that Mordechai's great-grandfather was exiled from the Land of Israel to Babylon. His niece Esther The Hidden, then, was also from this community of exiles, a descendant of people sent from their homeland, fully aware of their own Jewishness whether or not they could always reveal it to others.

As we read her story this Purim, let us honor the legacy of the many, many Crypto-Jews who risked their lives to try to preserve their tradition, and who often died in horrific, brutal ways, when the genocidal lots of the Inquisitorial death squads came to their door.

There are four central mitzvot of Purim: 1) giving money to those struggling to get by (a form of ancient mutual aid) 2) hearing Esther's story 3) sharing food treats (2 different kinds of food to two different people) and 4) having a festive meal.

If we observe the Fast of Esther the day before Purim, let us remember those who endangered everything to fast. And if we feast, maybe we can add a chickpea, spinach, and hearts of palm stew, or an eggplant caponata to our table.

May their memories of the slaughtered remind us how critical it is to fight for tolerance and freedom of every kind, for a world in which every person is able to be exactly who they are without fear.

Right now we are still able to fight back.

Perhaps, Mordechai reminds us, (Esther 4:14) for such a time as this we have gotten to exactly where we are right now.

🌱

Like this? Get more of it in your inbox every week.

For free every Monday—sign up at the ‘Subscribe now’ button just below.

And if you become a paid subscriber, that's how you can get tools for deeper transformation, a community for doing the work, and support the labor that makes these Monday essays happen.

A note on the subscription model:

I want my work to be as accessible to as many people as possible, in as many ways as possible. That's why the Monday essays are free, and why we donate subscriptions to anyone for whom paying is a barrier to the House of Study posts.

I also believe people should be paid fairly for their work. Needless to say, these two values sometimes seem to be in conflict, but I do what I can to find a fair balance. I offer many resources for free, and charge for others. When you donate generously or pay at the top of our scale, that helps support the work I do, provides access for those who have fewer resources, pays for the infrastructure and the technical and practical support that it takes to do this, and helps us keep the work sustainable.

And as always, if you want in to the Thursday space but paying isn't for you now, just email support@lifeisasacredtext.com and we'll hook you up.

And if you’d like to underwrite one of these donated subscriptions, you can do so by signing up at one of the higher subscription points.

And if it resonated with you, please share this post.

Sending a big pile of blessings and goodness your way. 💕

MORE ON PURIM: