It Was Never "Just Us"

Resisting Xenophobia in the Seder Narrative

This is Life as a Sacred Text 🌱, an everybody-celebrating, justice-centered voyage into ancient stories that can illuminate our own lives. It‘s run on a nonprofit, so it’s 100% NAZI FREE. More about the project here, and to subscribe, go here:

Well, hey, we've gotten to Deuteronomy 16, which has something to say about the holiday that begins this Saturday evening:

Observe the month of spring and offer a passover sacrifice to God your God, for it was in the month of spring, at night, that the God your God freed you from Egypt....You shall not eat anything leavened with it; for seven days thereafter you shall eat unleavened bread, bread of affliction—for you departed from the land of Egypt hurriedly—so that you may remember the day of your departure from the land of Egypt as long as you live..... (Deuteronomy 16:1-3)

Deuteronomy turns the story of Exodus into an annual event: Every year we do the Pesach/Passover sacrifice* and skip leaven (hametz) for a week to commemorate getting out, check.

*Well, there's no Temple now, so we put a shankbone or a beet on the seder plate instead.There are so many things to address all over the holiday, but this year let's jump down a few chapters. We see this, in the context of a ritual for bringing the first fruits of the harvest to the Temple; the person offering the fruits is supposed to say,

My father was a fugitive Aramean. He went down to Egypt with meager numbers and sojourned there; but there he became a great and very populous nation. The Egyptians dealt harshly with us and oppressed us; they imposed heavy labor upon us. We cried to the God of our ancestors, and God heard our plea and saw our plight, our misery, and our oppression. God freed us from Egypt by a mighty hand, by an outstretched arm and awesome power, and by signs and portents... [and so on....].. And so I now bring the first fruits of the soil... (Deuteronomy 26:5-8, 10)

Here, acknowledging the central identity story of the Judeans/Israelites is part of offering gratitude: Thanks, God, for bringing us into freedom, so that now I can harvest and give you these fruits. Makes sense, no?

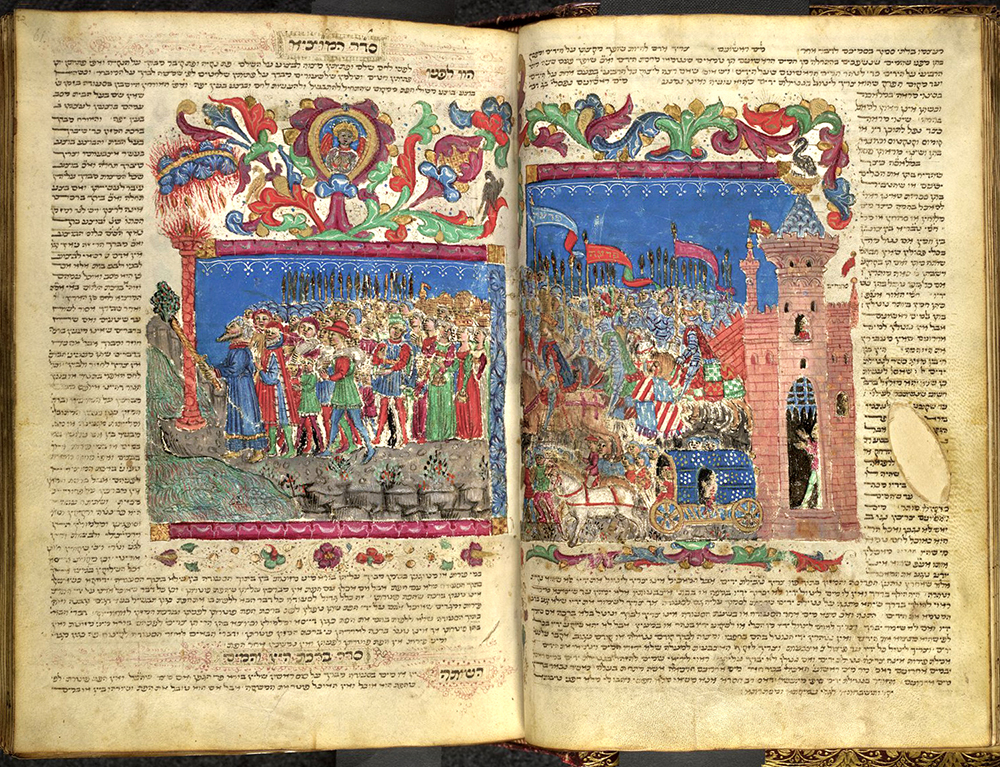

This summary of the whole Exodus story condenses chapters and chapters (entire books of Torah!) into five brief verses. It's so pithy that it gets included verbatim into the Haggadah, the book used to guide the Passover seder.

And what specific detail is important enough to get into this 5-verse summary? "My father was a fugitive Aramean." Not "Israelite." Not "Judean." My ancestor was an Aramean who came down to Egypt.

Wait– but, like, who was Aramean, though???

And Abraham said to [his] servant... "swear ...that you will not take a wife for my son from the daughters of the Canaanites among whom I dwell, but will go to the land of my birth and get a wife for my son Isaac.”... Then the servant...made his way to Aram-naharaim...He had scarcely finished speaking, when Rebekah, who was born to Bethuel, the son of Milcah the wife of Abraham’s brother Nahor, came out ...(Genesis 24:1-10, 15 abridged)

And!

So Isaac sent for Jacob and blessed him. He instructed him, saying, “You shall not take a wife from among the Canaanite women. Up, go to Paddan-aram, to the house of Bethuel, your mother’s father, and take a wife there from among the daughters of Laban, your mother’s brother....” (Genesis 28:1-2)

Genesis tells us that Abraham was from this region of Aram, now Syria (and also Ur; it's a bit both-and), as was Rebekah, and then that Rebekah's son and Abraham's grandson Jacob spent twenty years there– as a fugitive, running from his brother Esau's (understandable) anger. And this early text takes pains to not marry this family to the Canaanites in the Promised Land to which they arrive, but rather to go find spouses from among their kin.**

The text in Deuteronomy refers to Jacob, who gets renamed Israel– he was a fugitive Aramean, he went down to Egypt, and became a "great and populous nation," the people Israel. But it has taken pains to ensure that we know what his roots are.

**The wonderful journalist and historian Elon Gilad's The Secret History of Judaism has a brilliant theory about the origins of this Aramean thing. It's currently only in Hebrew, but I'll be sure to holler once there's an English translation!Perhaps unsurprisingly, the identification with Jacob/Israel as Aramaen and not, e.g., as Israelite or Judean was a bit discomfiting to the later People of Israel/Jews. So in the Geonic period (650-1075 CE), an additional midrash was added to the Haggadah to complicate our reading of this line.

As far as I can tell, the addition to the Haggadah was the first place that this text originated (but I could be wrong.) In any case, the addition was telling:

Go [to the verse] and learn what Laban the Aramean sought to do to our father Jacob: Pharaoh condemned only the boys to death, but Laban sought to uproot everything, as it is written: “AN ARAMEAN SOUGHT MY FATHER'S DEATH, AND HE WENT DOWN TO EGYPT...

An Aramean couldn't possibly be dad! So he had to be someone out to get dad! Never mind that in Genesis, Laban gave Jacob work and shelter for 20 years, made him rich, let him marry both his daughters, and then, when Jacob (who cheated Laban like whoa) snuck out to go back home, Laban chased him down to chastise him for not saying goodbye and to cut a covenant together. That dude loved his nephew/son-in-law.

At the heart of the Haggadah's interpolation is an insider/outsider tension. That is, this question of "us vs. not-us" and the determination that, if Deuteronomy didn't talk about "us," using the right words, then we'll jerry-rig some midrash to make sure that there's no question that this is "our" (Israelite! Jewish!) story, distancing our ancestor from any mention of a "not-our" nation.

And underneath that is a deep discomfort with any association of "our" ancestry, "our" story with people we perceive to be "not-us," right? Mmmm.

But– the Exodus was never an only-Israelite story.

For starters, liberation never, ever could have happened without the actions of at least one non-Jew. Pharoah's daughter– known by the tradition as Batya, the daughter of God, risks her own privilege and safety to interrupt injustice in the ways that she can and, critically, saves the infant Moses' life. As far as we know, there would be no Exodus without her. (It's also possible that the system-disrupting midwives Shifra and Puah weren't Israelite– we don't know.)

And then there's Exodus 12:38. It's go time, the moment to flee slavery and–

also a mixed multitude went up with them....

Erev rav, in the Hebrew. Rashi (the 11th c. French commentator) tells us that this was a "mixture of nations made up of strangers/sojourners," and Ibn Ezra (12th c. Spain) says it was explicitly Egyptians; the Late Antique/early Medieval Targum Yonatan says that it was "a multitude of strangers, two hundred and forty 'ten thousands' [myriads]" (That would be 2.4 million, yep). Samuel David Luzzatto (19th c. Italy) suggests that the mixed multitude is comprised of Egyptians who intermarried with Israelites. The Zohar (13th c. Spain) suggests that it's specifically Egyptian sorcerers and magicians who were dazzled by God's miraculous power.

Whoever they were, they weren't Israelites, but they, too, were part of the Exodus. They, too, were brought out of Egypt by God's plagues, by God's [metaphoric] mighty hand and [allegorical] outstretched arm, by all these signs and portents.

It was never "just us."

Our liberation has always been collective, it's always transcended border and boundary and the narrow place of identity.*** Our freedom has always included more than just us, it's always depended on more than just us, and it's always been about who else comes with us.

***Yes, Mitzrayim, Egypt, means "narrow place," from the root tzar, narrow.Can you imagine it? The Israelites are in the late stages of the plagues, beginning to get ready to go, to take reparations for their enslavement, and their non-Israelite neighbors say, Hey– you think it's really gonna happen this time? Can I come, too?

Of course the answer is yes. Of course the answer is: As many people free as possible. Of course the answer is: Yes, let's keep you safe. Of course the answer is, absolutely there is room for you, there is food for you, there is a place for you– we are all running, we are all refugees, and we are operating with an abundance mindset, we are leaning into these relationships of care and connection.

And who knows how it happened? Maybe the Israelites went to the Egyptians or other non-Israelites with whom they had longstanding bonds to say: Hey, looks like we're getting out, for real– you joining us? for all the same reasons.

For all the same reasons.

For all the reasons that Batya took that baby out of the Nile and decided to save his life.

For all of the reasons that the midwives risked their hides and lied to Pharaoh's face about having kept those babies alive in the first place.

Because every single person matters. Every single one.

The not–terribly–subtle xenophobia present in the attempt to distance Jacob from his Aramean roots is also present in some of the Rabbinic and later commentaries on the erev rav, of course– they were troublemakers! (In fact, the erev rav phrase is only used that one time in the Exodus story; later, in Numbers 11:4, when things get messy, the Hebrew word used is ʾasafsuf, despite a few later choices to translate them as the same word. Ahem.)

Or, the Rabbis say, the erev rav were all pious converts to Judaism! Never mind that it's clear in the Torah that gerim, strangers/sojourners/non-citizens, don't observe most mitzvot. OK, sure, that word– ger– grew to mean "Jew by choice" later, but in the biblical era, the Torah reminds us, again and again, that we Israelites "were gerim in the land of Egypt." We sure weren't converts, I'm imagining the Rabbis might agree.

Rather, Because we, too, were gerim, we should know not to oppress the ger–the stranger, the sojourner, the one who is not in their home country– and, rather, we must be just to gerim; to treat them with care; they shall be "as citizens;" and we must love them. Because our own communal-mythic and communal-historical experiences of alienation, of otherness, of oppression are meant to be the lenses through which we understand that the answer is always: Yes, you, too. Yes, of course. Come along. Whatever your national status, you're part of our community, too.

As Rabbi Rachel Barenblat put it,

I imagine us as a vast column of refugees walking together into the wilderness… and in that great crowd of people were people who were born into this community, as well as fellow-travelers who chose to accompany us on our journey toward freedom.... From the moment of our formation as a community, we are diverse.

Despite the tendency of this cultural moment to lock down– and to deport, to choose hate and anger and separation and division, to censor accurate history, unbiased reporting, or those who wish to speak on their own experiences, for fear of what it might unleash– our texts teach a different story.

We need not fear any of the components of our diversity, nor rush to rewrite any narrative that complicates our self-conception. Always choose truth over ugly propaganda trying to force our stories to be more simplistic than they really are. For the sake of what, exactly? That's the question to unpack, isn't it?

In every generation, a person is obligated to see themselves as though they, too, came forth from Egypt. (Mishnah Pesachim 10:5 and the Haggadah)

Together, with everyone. Together, inviting along all those who need to join. Together, unafraid of the truth, and checking our own long-held biases. Together, in solidarity with those whose lives may be very different from our own, whose story may be different from our own, who may put us at risk if we reach out to them– but who matter, desperately, as urgently as we do.

We must see and honor ourselves in our own complexity and love others in the beautiful truth of exactly who they are, on their own terms.

That is the path to liberation.

There is no other way.

Hag Pesach Sameach to all who are celebrating.

Next year in collective freedom.

🌱 ❤️ 🌱

It's time.

Join us!!

We need you in this community !!

previous posts and new (and new-ish) resources

A Feminist Look at the "Clear Out The Inner Chametz" Conversation

What The Plagues Might Have Done For the Enslaved Israelites

The Moral Challenges of the Tenth Plague

Discussion Questions on the Four Children:

Groovy Resources from Last Year:

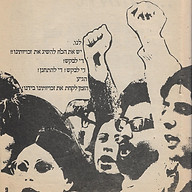

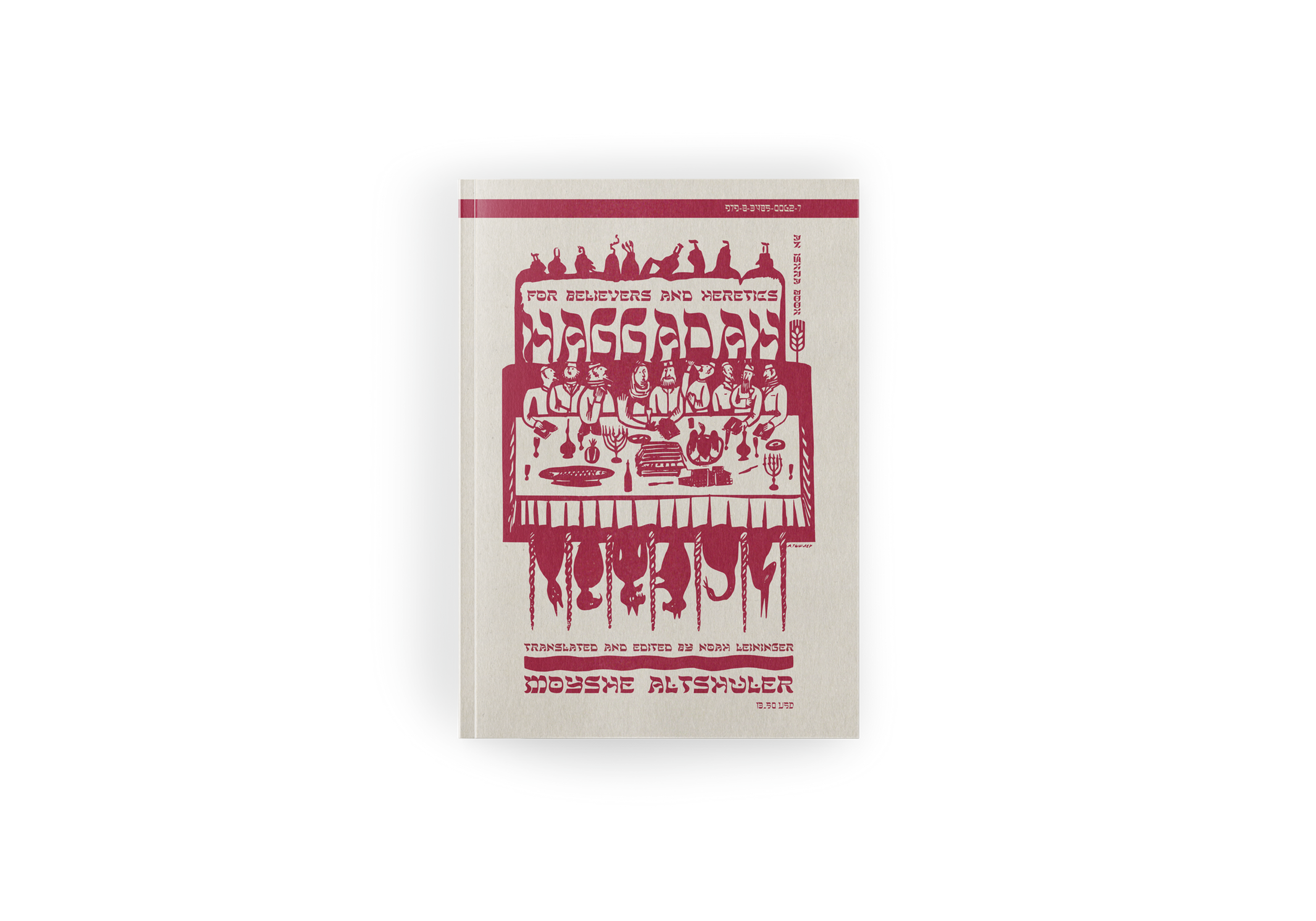

Including a bunch (but not all!) of the post below is dedicated to a Passover Haggadah published in 1919 by The Jewish Social Democrat Party, aka the Galician Bund.

And now – there's a new translation of the 1927 Haggadah (though I've also seen it dated as '22 and '23) published by the Soviet Commissariat of Nationalities (helmed by, uh, one Joseph Stalin), available at a discount or free PDF download. It is... very Soviet. And it should not be forgotten that, unlike the one created for and by secular Jews, above, this was created by the State, aimed at turning the Jewish population of newly-Soviet Russia into an ethnic, rather than religious community, and lives in the shadow of everything that happened to Jews there after. That said, some of you will enjoy this very much, so zei gezunt.

The Israeli Black Panthers Haggadah was first written in 1971, at the beginning of their protest movement of Sephardi and Mizrahi Jews fighting against Ashkenazi supremacy, drawing inspiration from the US Black Panthers movement. It was written in a dark tin shack in Jerusalem on a stolen typewriter. Reuven Abergel, one of the founders of the movement, writes that the Haggadah talks "about the pain, discrimination, and oppression that we were subjected to as part of Israel's policy of separation between Jews from Muslim countries and Jews from Eastern Europe." It's now translated into English, with a free PDF preview available:

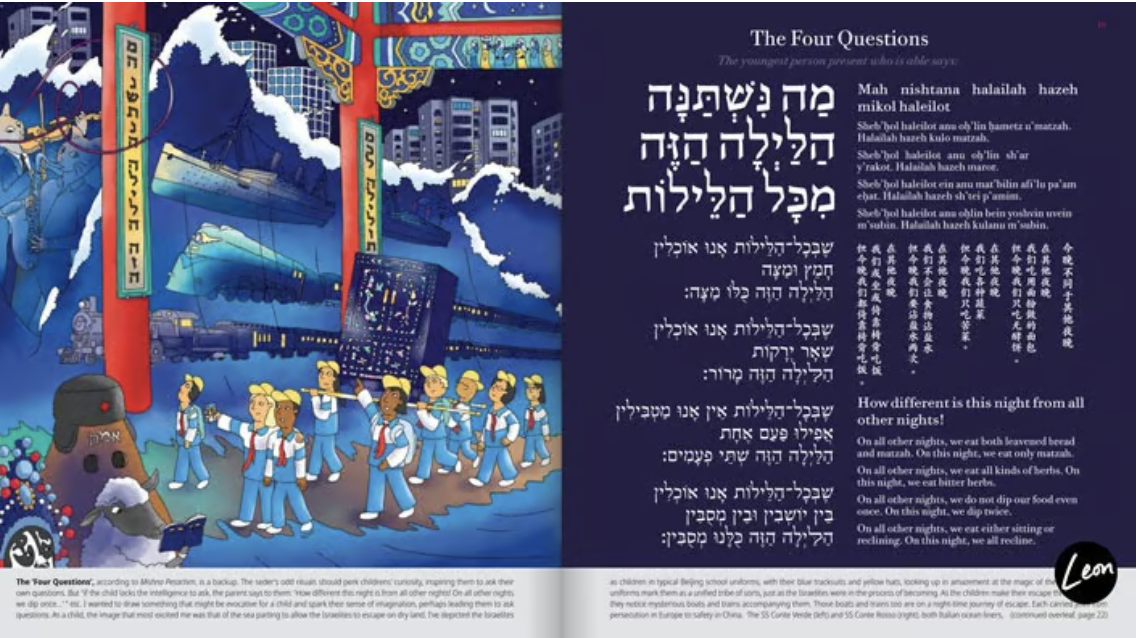

The Beijing Haggadah: Leon Fenster now lives and works in the Taiwan Jewish Community (that's the official name), but spent many years, himself, in the Beijing community; he taught at Tsinghua University on the connections between the Chinese diasporic experience and his dreamlike Jewish urban art. In the Beijing Haggadah, he writes out the traditional text in Hebrew, English and Chinese and uses local landmarks and community members in the art. It was developed in collaboration with the Beijing Jewish community, as far as I'm aware. Order here.

🌱

Like this? Get more of it in your inbox every week.

For free every Monday—sign up at the ‘Subscribe now’ button just below.

And if you become a paid subscriber, that's how you can get tools for deeper transformation, a community for doing the work, and support the labor that makes these Monday essays happen.

A note on the subscription model:

I want my work to be as accessible to as many people as possible, in as many ways as possible. That's why the Monday essays are free, and why we donate subscriptions to anyone for whom paying is a barrier to the House of Study posts.

I also believe people should be paid fairly for their work. Needless to say, these two values sometimes seem to be in conflict, but I do what I can to find a fair balance. I offer many resources for free, and charge for others. When you donate generously or pay at the top of our scale, that helps support the work I do, provides access for those who have fewer resources, pays for the infrastructure and the technical and practical support that it takes to do this, and helps us keep the work sustainable.

And as always, if you want in to the Thursday space but paying isn't for you now, just email support@lifeisasacredtext.com and we'll hook you up.

And if you’d like to underwrite one of these donated subscriptions, you can do so by signing up at one of the higher subscription points.

And if it resonated with you, please share this post.

Sending a big pile of blessings and goodness your way. 💕