taking a holy time out

When it's time to do some serious spiritual heavy lifting, taking a break from things that make it difficult to hear that still small voice within is sometimes key.

This is Life as a Sacred Text 🌱, an expansive, loving, everybody-celebrating, nobody-diminished, justice-centered voyage into one of the world’s most ancient and holy books. We’re working our way through Numbers these days. More about the project here, and to subscribe, go here:

Today we're going to look at the strange case case of the nazirite– a wild-haired holy ascetic about whom we don't know nearly enough– but we can connect a few of the dots, learn about a couple of the women who took on the mantle later in history, and get some inspiration for our own lives.

And, your regular reminder that this is an independent project that exists entirely with the support of readers, so if you're not yet a paid subscriber, consider leveling up to get guided text studies, Q&As, sekrit backstories and process stuff, and more. (And if you want those things but paying isn't for you, you can always email support@lifeisasacredtext.com for a hookup.)

Let's just jump into the text of Numbers 6 without too much preamble.

If anyone, man or woman, that explicitly vows the nazirite vow, to set themselves apart for God, (Numbers 6:2)

First of all! ANYONE COULD TAKE THIS VOW! (Yep, women, too! We'll look at a couple of historical women who took the vow down below.) You didn't have to be special or anything. That's actually a big deal; you'll see as we go.

In biblical Hebrew, נזר in its verb form is translated as, "to consecrate," but as a noun, it means "crown." (In modern Hebrew, it's a tiara.) Its origin, here, probably refers to the crown of the head (since, as we'll see in a second, this status has a lot to do with the hair.)

There are a couple of key components to becoming a nazirite.

First:

they shall abstain from wine and any other intoxicant... neither shall they drink anything in which grapes have been steeped, nor eat grapes fresh or dried. (Numbers 6:3)

Sobriety. (Straight edge/sXe, as we called it back in the day.)

This is significant, on a number of levels.

First of all, wine was a key part of ancient Near Eastern society– in celebrations both sacred and secular, and not infrequently as part of the day-to-day (remembering, of course, that safe, potable water was not as easy to come by as it is today.)

So abstaining– then as now– had significant social implications.

The decision to voluntarily abstain from wine and etc. meant, in many ways, setting oneself apart from the rest of one's culture. And though Judaism is generally perfectly comfortable with booze in moderation (and, sometimes, a bit in excess, let's be real), but the decision to just say no was understood to be part and parcel of dedication to a higher level of sanctity.

The writer and scholar Carol Lee Flinders suggests that

...every great undertaking begins with some form of asceticism, including political resistance work... it looks to me as if all forms of mysticism share the understanding that "prayer and sacrifice" or "meditation and renunciation" are of the essence. Training the mind, and redirecting desires. Simplifying thought processes and life at the same time—the two efforts requiring one another.

Spiritual self-care demands constant attention to the small voice that murmurs barely-comprehensible information about what one needs from moment to moment.

When it's time to do some serious spiritual heavy lifting, taking a break from things that make it difficult to hear that voice is sometimes key.

It's no coincidence that the mystical sects of many religious traditions weigh in on the consumption of meat and alcohol, and that countless contemporary teachers have suggested taking breaks from our phones, from social media; certain things really do affect one's inner state. I have one friend who stopped eating chicken during her first couple of years in seminary, and other friends have gone celibate or stayed away from news headlines while they were deep into a certain stage of some great internal undertaking.

In the days after the writer Kathy Acker had a particularly profound experience during meditation, she found that she was rather discombobulated, clumsily bumping into cars and the like. She asked her Zen master how to come down off the high, and he said, "You're supposed to enjoy it! Oh—go get drunk!" So she did. The foreign substance served as the antidote to her elevated condition. If Acker had wanted more of the blissy feeling, she should have stayed away from anything known to bring a person "down"—but for her, it was time to get back to her regular state of mind.

So the nazirite vow being one away from all "intoxicants" signals an intention to doing deeper spiritual work than they would be able to otherwise– both because they're refraining from the sauce for a bit, and because, I suspect, they're taking a break from all that socializing.

The next key nazirite component:

Throughout the term of their vow as nazirite, no razor shall touch their head; it shall remain consecrated until the completion of their term as nazirite of God, the hair of their head being left to grow untrimmed. (Numbers 6:5)

The famous one: Let that hair grow. (Until the end of the term, at which point it is cut off and offered as part of the sacrifice marking the end of their term).

This, too, it's generally understood, is meant to help set the person apart from "polite" society, if you will. For, as the Sefer HaChinuch ("The Book of Education,"), a 13th c. Spanish text put it,

"there is no doubt that both very long hair and completely shaven heads destroy the appearance of a person." (Sefer HaChinuch 374.2)

Well, that's a pretty judgey thing to say, Anonymous Thirteenth Century Guy, but I think it is part of the point, here.

You know who took the vow because of their hair– you can identify them on sight. Their hair is supposedly wild, unkempt. And then it all gets shorn off.

It's another way to re-ground in what really matters.

Shimon HaTzaddik [told of meeting a nazirite]: who came to me from the South, who had beautiful eyes and a fine countenance, and his locks were arranged in curls. I said to him: My son, what did you see to become a nazirite, which would force you to destroy this beautiful hair, as a nazirite must cut off all his hair at the conclusion of his term? He said to me: I was a shepherd for my father in my town, and I went to draw water from the spring, and I looked at my reflection in the water. And my evil inclination quickly rose against me and sought to drive me from the world. I said to my evil inclination: Empty one! For what reason are you proud in a world that is not yours, as your end is to be maggots and worms when you die. I swear by the Temple service that I will become a nazirite and shave you for the sake of Heaven. (Talmud Nazir 4b)

This hot shepherd realized that he was a little too taken with his looks– and that the way out was a vow that would focus his attention on the Holy One, and shed those lovely locks.

And lastly, stay away from dead bodies. No getting death cooties, aka tumat met– the highest status of ritual impurity possible. (1) This might even mean staying away when family members are dying. There were significant ramifications to this vow.

In all these ways, this vow was about the obligation

to set themselves apart for God. (Numbers 6:2)

What else do we know?

The nazirite had similarities and/or connections with a couple of other important roles.

For example, another group of people that had to

- Stay away from booze (when working, at least)

- Who had to keep away from dead bodies, and

- Who were described as having "the crown (nezer) of God.. upon their head" (Numbers 6:6/Leviticus 21:11) were...

priests!

and!

b) the other group of people they were often linked to were, as God-the-narrator put it... drumroll

And I raised up prophets from among your children

And nazirites from among your youths. (Amos 2:11)

And, in fact, there seems to be a bunch of overlap on the prophet/nazirite situation. In the Book of Kings, someone asked: Hey, who was that weird holy guy rebuking the king for consulting with Phoenician deities?

They replied: “A man with a lot of hair, with a leather belt tied around his waist.” “That’s Elijah the Tishbite!” he said. (II Kings 1:8)

(Yeah, the prophet Elijah.)

When the prophet Samuel's mother, Hannah, was praying for a child, she begged God,

If You will grant Your maidservant a child ... I will dedicate them to God for all the days of their life; and no razor shall ever touch their head.” (I Samuel 1:11)

And though the version of the Bible that we use doesn't say explicitly that he was supposed to be a nazirite, it's pretty much understood– and a version found as part of the Dead Sea Scrolls– some of the oldest existing copies of books of the Hebrew Bible–makes it explicit:

And I [shall make] him a nazirite forever, all the days [of his life]. (4QSama1:22)

And the first Greek translation of the Hebrew Bible (called the Septuagint) adds that he's not going to get wine or haircuts, either.

So. Even if we're a lil' fuzzy on the exact job description, the nazirite is somewhere in the neighborhood of a priest or a prophet.

And it seems like the prophet/nazirite mashup was not super uncommon.

Except– this could be for anyone. Any regular schmo could take a vow to make themselves like a priest or a prophet.

So what about that one guy?

Yep, the most famous of them all, Samson. (1)

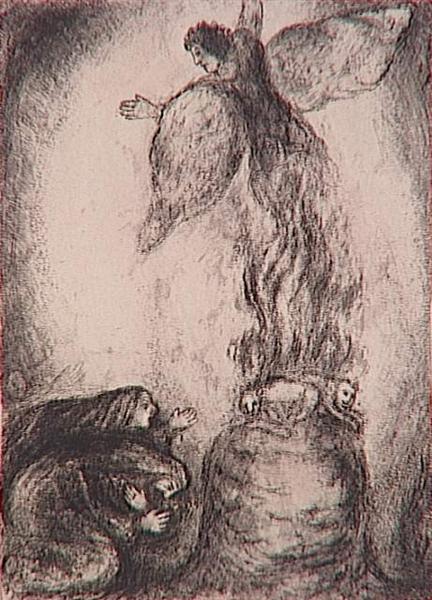

Interestingly, he's consecrated as a nazirite in utero, and connected to this consecration is something of a "chosen one" status:

"An angel of God appeared to the woman and said to her, “You are infertile and have borne no children; but you shall conceive and bear a son. Now be careful not to drink wine or other intoxicant, or to eat anything impure. For you are going to conceive and bear a son; let no razor touch his head, for the boy is to be a nazirite to God from the womb on. He shall be the first to deliver Israel from the Philistines.” (Judges 13:3-5)

Like Samuel, this nazirite destiny is to be his from birth, and like Samuel, Samson is not given the opportunity to choose.

We'll look at his story a bit more next week, just because it's so rich and it's impossible to skip while we're over here.

But what's notable is that both Samuel— who played a key role in the transition from the biblical judges to the monarchic era– and Samson, who was also part of the era of the judges– long pre-dated the authorship of Numbers 6. (The era of the judges ended ca. late 11th c. BCE.)

Both Dr. Tzemah Yoreh, author of Why Abraham Murdered Isaac, on the Supplementary Hypothesis to biblical authorship, and Richard Elliot Friedman, who holds by the Documentary Hypothesis, agree that Numbers 6 was written by the Priestly Source, which was later than this time– at least after the Assyrians destroyed the Northern Kingdom of Israel in 722 BCE, possibly even after the Babylonian destruction of Judea in 586 BCE.

It's possible that by then, it was much more understood that people were to voluntarily take on this vow.

To "set themselves apart for God."

Choosing to go there. (2)

For a specified amount of time. Not their whole lives! Just a certain amount of time– however long they've declared that time to be– in order to offer of themselves. To connect in this way. To take this holy time out.

I want to look at a couple cases of historical nazirot– female nazirites– and then I'll bring this all back around to us again.

Especially after last week (and, uh, a lot of stuff in this Ancient Near Eastern document) it's nice to see women here get a chance to exercise agency at all, especially around something unrelated to gender or gender roles.

Josephus, the Jewish defector to the Romans during the revolt against Rome, wrote the following about Berenice of Cilicia, the daughter of Herod Agrippa (the last Jewish king of Judea), during the Great Jewish Revolt of 66 CE:

Now she dwelt then at Jerusalem, in order to perform a vow which she had made to God; for it is usual with those that had been either afflicted with a distemper, or with any other distresses, to make vows; and for thirty days before they are to offer their sacrifices, to abstain from wine, and to shave the hair of their head. Which things Bernice was now performing, and stood barefoot before Florus's tribunal, and besought him [to spare the Jews]. Yet could she neither have any reverence paid to her, nor could she escape without some danger of being slain herself. (Josephus, War of the Jews, 2:15:1)

She undertook the nazirite vow– a queen who chose to dedicate herself to God, going humiliatingly to the Roman imperial governor of Judea with hair shorn, barefoot, risking her life and begging him to spare the Jewish people in the wake of the revolt. (Sadly, she failed.)

Imagine her emotional and spiritual state in the thirty days leading up to this moment, given all we know about the inner work the nazirite vow can engender. (3)

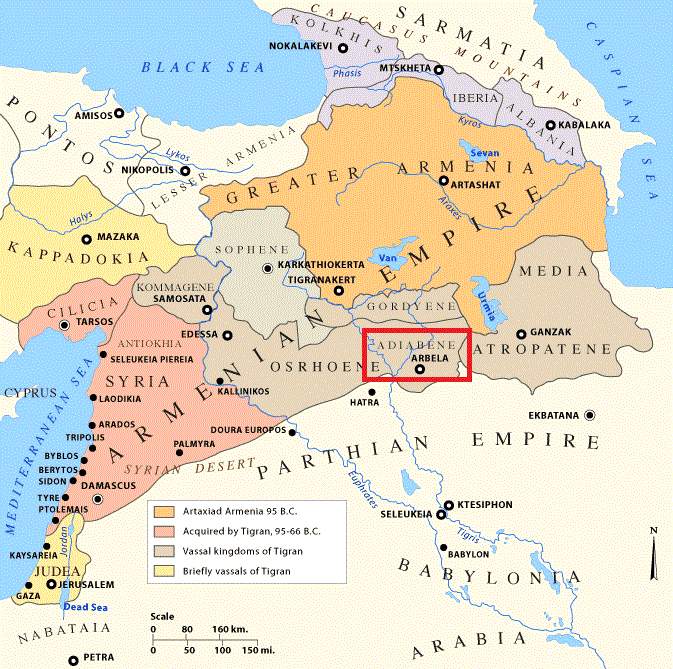

And then there's this story about a Jew by choice named Helene, who was Queen of Adiabene (an ancient kingdom in northern Mesopotamia that covered, I think, the area where modern-day Turkey, Iran and Iraq meet.)

An incident occurred with regard to Queen Helene, whose son had gone to war, and she said: If my son will return from war safely, I will be a nazirite for seven years. And her son returned safely from the war, and she was a nazirite for seven years. And at the end of seven years, she ascended to land of Israel, and The School of Hillel instructed her, in accordance with their opinion, that she should be a nazirite for an additional seven years [since she started and completed a long vow while outside the Land of Israel and then came to the Land of Israel--their ruling is that she, as others, should start over]. And at the end of those seven years she became ritually impure, and was therefore required to observe yet another seven years of naziriteship, as ritual impurity negates the tally of a nazirite. And she was found to be a nazirite for twenty-one years. Rabbi Yehuda said: She was a nazirite for only fourteen years and not twenty-one. (Mishnah Nazir 3:6)

So she had made a vow to take on the nazirite mantle for seven years if her son got home safely, but when she got to Jerusalem from her far-away home, she learned that Jewish law had a different take on big nazirite vows made outside the Land of Israel. So she just kept it up and kept it up– a testament, this story seems to underscore, to her piety.

Dr. Malka Zeiger Simkovich makes the observation that these are two stories about queens, both semi-outsiders. How common was it for women to take on this vow? Were these women more able to do so because they had more agency than normal women because of their status? Was it a relatively common thing but we're only hearing these stories because of their status? We will never know.

But here's what we do know:

- There are times when it may be Correct to take a break from the things we use to numb out– intoxicants, be they alcohol, drugs, (or, depending on your drug of choice, screens, sex, spending, or something else) – so that we can better hear ourselves, and connect to the Big Bigness that surrounds and binds us all.

- Those times don't have to be forever (though for some people that might be for the best, if those things are particularly addictive or harmful). For many folks, it might just be, "for a bit," "for right now," "for a few weeks or a month," or etc.

- During those times especially, perhaps it's OK also to say no a little more often to the social routines in which we are usually embedded. To step to the side, to make space for something else to happen.

- These are the times when it may be especially useful to get a reality check on our culture's expectations about appearance, beauty standards, body image, how we have been showing up in the world and why, how much energy we put into the artifice– and what might happen if we let go of that to focus on the more urgent, primal matters deep within.

- This vow was for anyone. The choice to do these things can help us get in touch with the parts that live inside all of us that are sacred and prophetic. They may not be immediately comprehensible to others, but that wildness is profoundly holy.

We must not underestimate it.

I leave you with one of my favorite poems, by the Palestinian-American poet Naomi Shihab Nye:

The Art of Disappearing, Naomi Shihab Nye

When they say Don’t I know you?

say no.

When they invite you to the party

remember what parties are like

before answering.

Someone is telling you in a loud voice

they once wrote a poem.

Greasy sausage balls on a paper plate.

Then reply.

If they say We should get together

say why?

It’s not that you don’t love them anymore.

You’re trying to remember something

too important to forget.

Trees. The monastery bell at twilight.

Tell them you have a new project.

It will never be finished.

When someone recognizes you in a grocery store

nod briefly and become a cabbage.

When someone you haven’t seen in ten years

appears at the door,

don’t start singing him all your new songs.

You will never catch up.

Walk around feeling like a leaf.

Know you could tumble any second.

Then decide what to do with your time.

Like this? Get more of it in your inbox every week. 🌱

For free every Monday—sign up at the ‘Subscribe now’ button just below.

And you can get even more as part of a community of rabble rousers going deep into the questions and issues, with even more text and provocation, every Thursday.

And please know that nobody will ever be kept out due to lack of funds. Just email lifeisasacredtext@gmail.com for a hookup.

And if you’d like to underwrite one of these donated subscriptions, you can do so by signing up at one of the higher subscription points.

And if it resonated with you, please share this post.

Sending a big pile of blessings and goodness your way. 💕

[1] Samson!

[2] Dating of Numbers and Samson's stories

[3] Berenice

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the beginning of his story is the Haftarah (uh, section from the prophets) that gets read with the Torah portion that includes the nazirite verses. ↩︎

It's also possible that the priestly folks added in the "no contact with the dead" bit to make the nazirite more parallel to their own role, or to be able to have more control over the nazirite. As anyone who knows the Samson story can attest, "the dude who kills lots of people, in multiple scenes" wasn't really particularly aces about staying away from dead bodies. Nor was his mother warned about this during her annunciation scenes. The more ancient version of the nazirite just might not have had this as a requirement. ↩︎

Berenice eventually sided with the Romans as the Jewish Revolt wore on, and then she fell in love with, and ran off with, Titus, the guy who destroyed the Second Temple, so her legacy as a Jewish leader is... mixed at best. ↩︎