notes towards a theology of prose

Exploding our creative boundaries can help us seek a connection with the divine that is lived, messy, and sublime.

This is Life as a Sacred Text 🌱, an everybody-celebrating, justice-centered voyage into ancient stories that can illuminate our own lives. It‘s run on a nonprofit, so it’s 100% NAZI FREE. More about the project here, and to subscribe, go here:

Purim's coming up (starts Saturday night.) The Megillah of Esther the only book in the Hebrew Bible (except the Song of Songs) that does not mention God's name explicitly. (1)

So, hey, I thought this might be a nice time to bring some theology into the conversation.

These are some ideas that I began noodling around with a couple of decades ago, while in rabbinical school, but that I've brought back to life and updated just now, for all of you.

Some context: My favorite writers, for many, many years (and also, like, not not now), had a thread running through them– they are those who have done wild, experimental, dreamy, fragmentary, stream-of-consciousness, expansive things not just with ideas, but with prose itself.

When I was in rabbinical school, I wrote (this whole vintage section goes until the next photo):

"I’ve just begun thinking about how my past influences–particularly in terms of writing, particularly when I was still writing in the realm of fiction–have impacted the way that I think theologically. That is to say, I wonder if my years working in that gray area between poetry and prose–in the tradition of Carole Maso, Monique Wittig, and Virginia Woolf, among others–has had a direct impact on the way I think about God.

I’m not particularly interested in absolutes or answers, and I’m not certain that we can find them. I’m perfectly comfortable holding two (or more) contradictory understandings of the divine in one place, and allowing them both to be true–or truth, anyway. I’m constantly allowing my understanding of God to shift the way my understanding of what form my work used to take would shift.

Virginia Woolf accused James Joyce’s Ulysses of not ever going beyond the self.

Perhaps its rigid structure bound it to itself, mitigated any possibility of transcendence.

Keats wrote,

“Philosophy will clip an angel’s wings

Conquer all mysteries by rule and line

Empty the haunted air, and gnomed mine

Unweave a rainbow….”

I think the novel can, too, sometimes, if it’s too tightly bound.

Behold, it is explicitly stated in the Torah and [the works of] the prophets that the Holy One, blessed be God, is not [confined to] a body or physical form...Were God [confined to] a body, God would resemble other bodies. (Maimonides, Laws of the Foundation of Torah, 1:8)

In an open space, surprises can emerge.

Habituation and expectations can make fools of us all, if we're not paying attention to what's happening now, here, today.

Too much attachment to one understanding of how things are, how things are supposed to go will limit what we’re able to perceive: The mysteries will be conquered, the air emptied before we ever knew what was there in the first place.

It’s possible to have certainty without any understanding that the air was ever haunted.

Even, or especially in religion.

Exploding our creative boundaries can be one way of entering into a relationship with the divine that is lived, messy, and sublime, defying any attempt to sweep God, or ourselves, into tidy categories that ultimately mean nothing.

What do we miss when we’re too attached to the form we think something should take?

If we allow language to push past its usual comforts and conventions, how might that impact the way in which we experience our own lives?"

There is a moment in the Book of Numbers when we see Moses hitting a wall. He's not sure he can deal with the Israelites anymore, or why they have to be his responsibility in the first place. He turns to God and says,

"Did I conceive all this people, did I birth them, that You should say to me, 'Carry them in your bosom as a wetnurse carries an infant,' to the land that You have promised on oath to their ancestors?" (Numbers 11:12)

Moses points out to God that he has done nothing to deserve this burden of leadership, and uses the powerful language of childbearing and mothering in order to do so.

God, here is cast as the mother who, rather than Moses, conceived and birthed this nation.

Every expression of the divine is a metaphor. Every single one. But, for some reason, both Jews and Christians seem to pass over this particular metaphor ... a lot.

There are a select few traditional Jewish commentators who will even acknowledge the maternal birthing trope inherent in this verse (shoutout Nachmanides), and so many more who find unbelievable ways to explain its obvious plain meaning. They've said that Moses is talking about a man contributing semen to the babymaking process; about a man raising children; about a rabbi teaching students Torah; or they just gloss over that and focus on Moses' exasperation, and ignore the language entirely.

The expansive possibilities invited by this the divine metaphor–what it could offer our theological thinking, where it could take our understanding, our spirituality, our practice—are almost always entirely obscured.

Not only talking about "the divine feminine," for example– as Maimonides notes, God doesn't have a body, though as Judith Plaskow observes, Maimonides and all these other guys never do manage to ask hard questions the pronouns they use for the Infinite Big Bigness, and our language does help create our experiences.

But also, like– for example, this one verse offered me a lot for my book on parenting as a spiritual practice.

And that's not even enough. That's a small, pitiful example that doesn't take things nearly as far as I want us to go.

But it illustrates how hard people sometimes work to stay inside their self-imposed boundaries, and what can be lost when they do.

Carole Maso asks in the appropriately-titled, essay, "Break Every Rule,"

“If the creation of literary texts affords a kind of license, is a kind of freedom, dizzying, giddy–then why do we more often than not fall back on the old orthodoxy, the old ways of seeing and perceiving and recording that perception?”

It is certainly not the case that all the authors of this kind of prose are queer women and nonbinary people, but wow, a lot of them are.

For them, style, form, was (often) both an artistic and political choice.

For example, Monique Wittig's Les Guérillères, a futuristic tale about warrior women overthrowing patriarchy begins an investigation into style that would become even more radical in her subsequent book, The Lesbian Body, but even here she makes her intentions clear about the relationship between language and liberation:

They say, take your time, consider this new species that seeks a new language. A great wind is sweeping the earth. The sun is about to rise. The birds no longer sing. The lilac and violet colours brighten in the sky. They say, where will you begin? They say, the prisons are open and serve as doss-houses. They say that they have broken with the tradition of inside and outside, that the factories have each knocked down one of their walls, that offices have been installed in the open air, on the esplanades, in the rice-fields.

A new species that seeks a new language. As barriers are broken, as freedom is created.

Maso continues, later in her same iconic essay:

"If we joyfully violate the language contract, might that make us braver, stronger, more capable of breaking other oppressive contracts?"

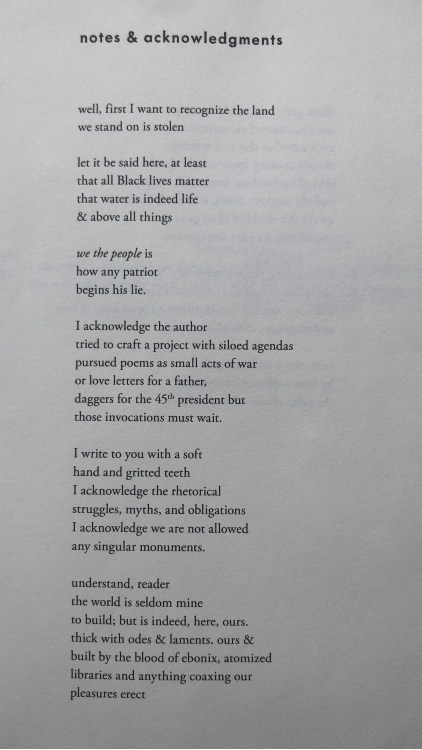

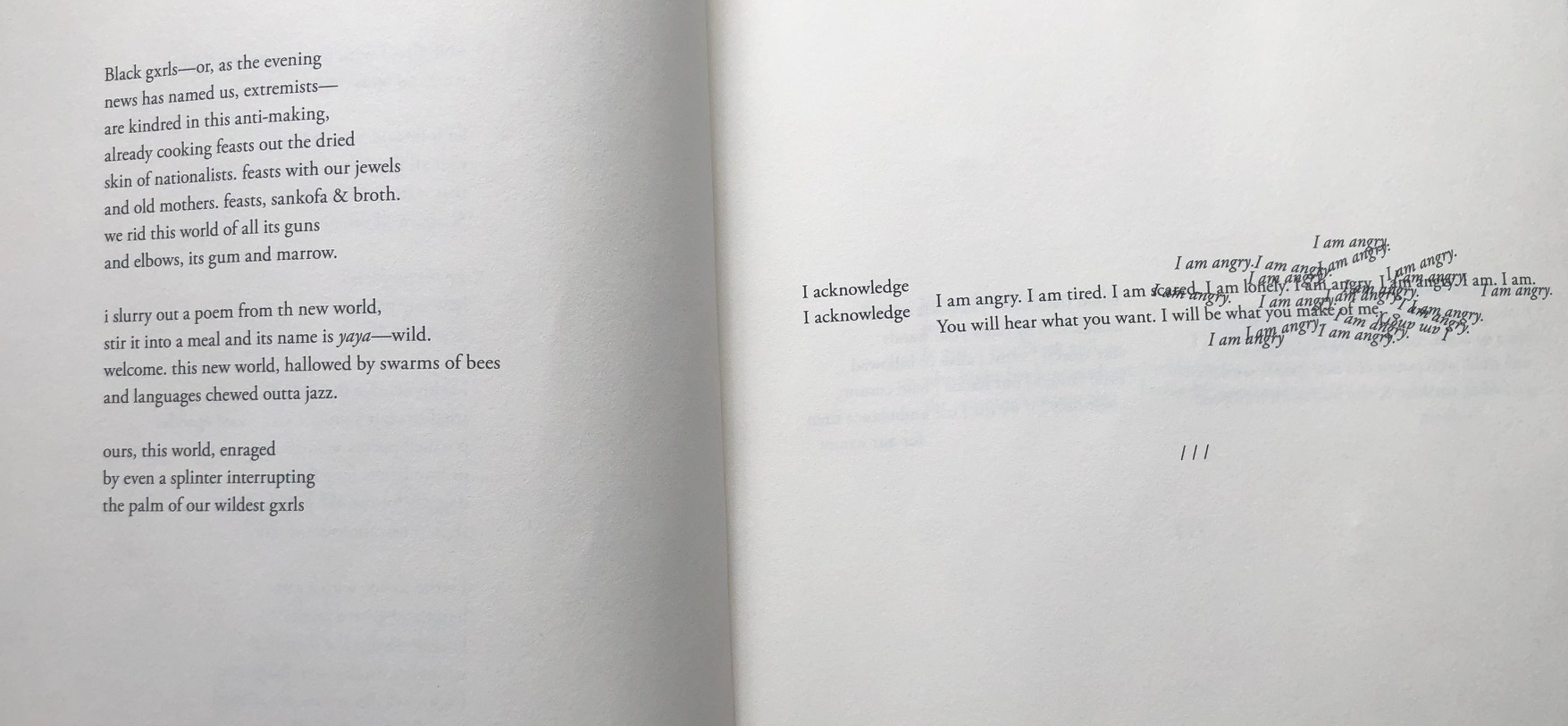

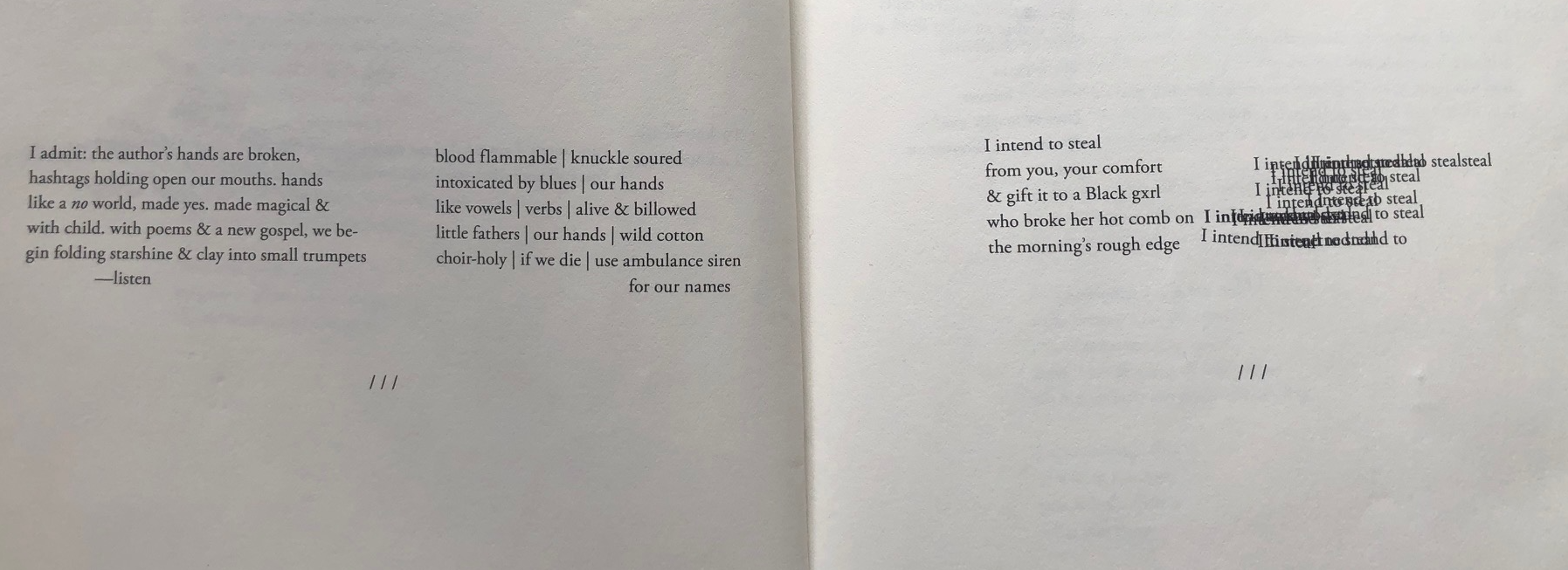

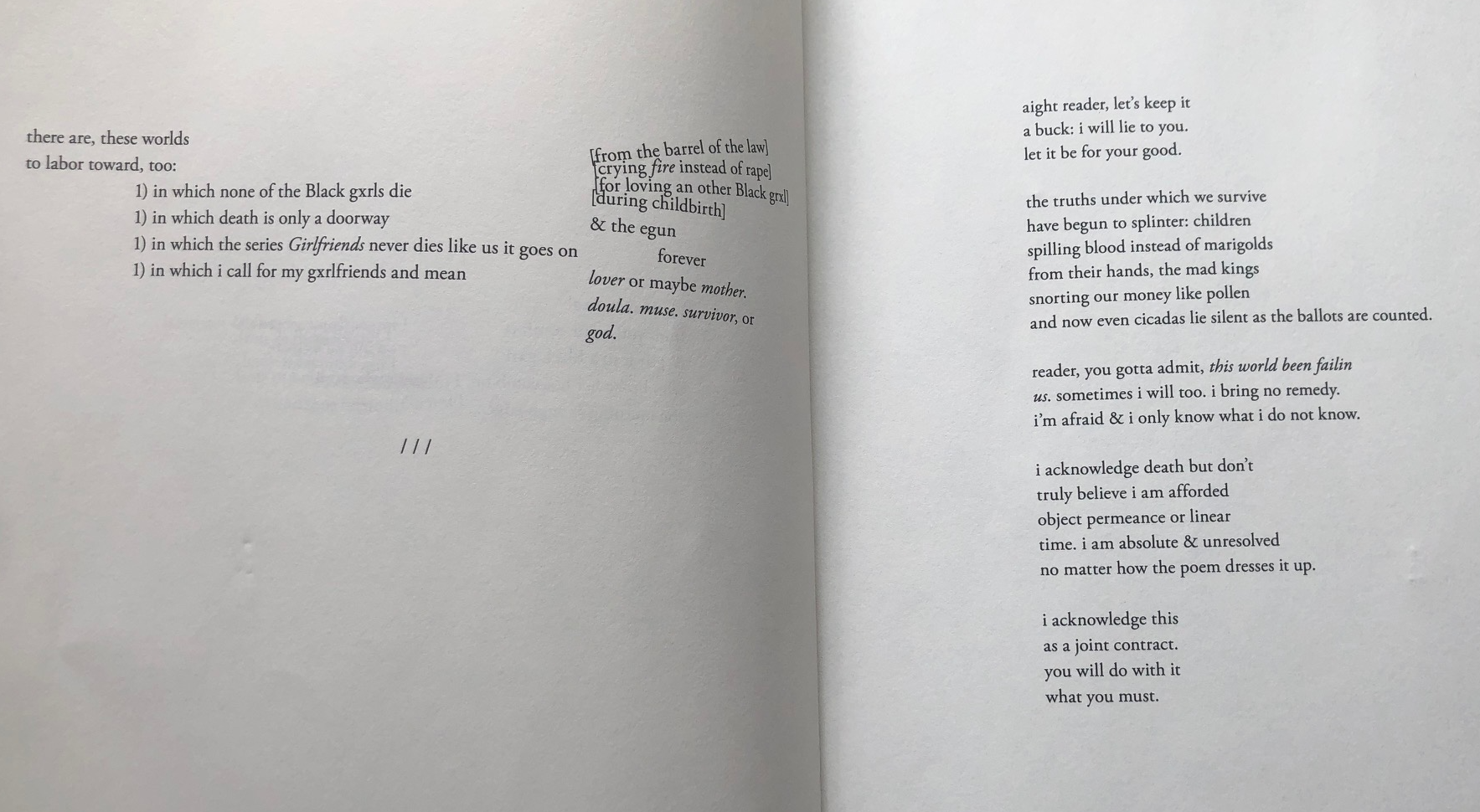

Aurielle Marie, author of the exquisite Gumbo Ya-Ya, written for "Black gxrls and womxn" has said, of the ways their words explode– sometimes quite literally– on the page,

It took me a long time to realize that this push toward the singular, the conventional, was itself an iteration of the very same anti-Blackness my book was trying to reveal. Gumbo Ya Ya is about the multiplicity, the polyphonic, the fugitive mechanics of Blackness, and I realized that I was policing the execution of such a thing. So I gave myself permission to explore what it looked like to build poetic articulations of fugitivity and multiplicity. Repetition and stacking became the vessel for the thing I had been running from.

And that for Marie, the urge to constrain became an attempt to limit our experience of truth:

I don’t think we should shy away from the messiness of life, and I loathe the way we’re taught to use form to “neaten” the mess of a poem.

Moses, our teacher, asked that the existence of the Holy One, blessed be God, be distinguished in his mind from the existence of other entities, to the extent that [Moses] would know the truth of God's existence.. God replied that it is not within the potential of a living person, [a creature of] body and soul, to comprehend this matter in its entirety. (Maimonides, Laws of the Foundation of Torah, 1:10)

What it offers.

Perhaps we should stop making assumptions about how things are supposed to be, resist the urge to get too comfortable– to be open to everything that might get us to a "dizzying, giddy freedom."

Because we might be missing critical things from where we are.

We have, perhaps, gotten too comfortable with our theological ideas and experiences.

With our own ways of being and doing in the world.

With what we consider acceptable, systemically.

It may be time to push beyond the familiar, the known– to, as Wittig puts it, "seek a new language."

שִׁירוּ לַה' שִׁיר חָדָשׁ

Sing to God, sing a new song. (Psalm 96)

To seek that which can better connect us beyond the tidy boxes into which we have so comfortably poured our religious lives.

That which helps us to find new ways of experiencing who we are.

And of course, the liberation in this theology is implicit– to find ways to vision new, less oppressive paradigms for our society as a whole.

Is such the fast I desire, A day for people to starve their bodies? Is it bowing the head like a bulrush And lying in sackcloth and ashes? Do you call that a fast…? No, this is the fast I desire: To unlock fetters of wickedness, And untie the cords of the yoke To let the oppressed go free; To break off every yoke. (Isaiah 58:5-6)

But where is tradition in this? I hear so many of my colleagues saying.

(Hi, guys! 🙂)

Candidly: I don't have a single pat answer–it's not not there, this isn't a dissertation and I don't have it all worked out– I imagine the roots of the tree that is still growing, the treasures of the storehouse still– treasures. Still ours.

These are notes, rough and incomplete, this is a sketchbook of ideas, one piece of the puzzle.

But I'll tell you this much: Our existing paradigms have created spaces and theologies, philosophies of halakha/Jewish law and ways of living in community that are still deeply racist and misogynist, ableist, homophobic and transphobic, that protect power over the interests of justice or those harmed all too often.

There is so much good in our community and in our tradition but there are fundamental failures in our religious and communal understandings as well. And they’re all interconnected. How we talk about authority and wisdom and teachers and what values are transmuted to our children and congregants about whose voice matters and why, so many things.

None of the writers I have cited threw out form entirely, nor did Maimonides when he threw out every precedent of relationship to the Talmud and... most or all of them when talking about God.

Nor did Isaiah when he demanded better of his community.

The centermost verse of Torah–the clal gadol, the great principle, according to Rabbi Akiva, is still (Sifra, Kedoshim 4:12)

Love your neighbor as yourself: I am God. (Leviticus 19:18)

And Hillel still said, (Shabbat 31a)

“That which is hateful to you, do not do to another; that is the entire Torah.”

And it's still written, (Genesis 1:27)

“So God created the human in God’s own image, in the image of God created them.”

Just as Maso and Wittig and Woolf and Marie couldn't do what they did without drawing from their roots but also being willing to set things free.

Perhaps, if God is hidden in this– or any – season, we can look at some of the walls within that need to be broken down in order to begin to find God once again.

🌱 ❤️ 🌱❤️🌱 ❤️ 🌱❤️ 🌱 ❤️ 🌱❤️🌱

Like this? Get more of it in your inbox every week. 🌱

For free every Monday—sign up at the ‘Subscribe now’ button just below.

And if you become a paid subscriber, that's how you can get tools for deeper transformation, a community for doing the work, and support the labor that makes these Monday essays happen.

And as always, if you want in to the Thursday space but paying isn't for you now, just email support@lifeisasacredtext.com and we'll hook you up.

And if you’d like to underwrite one of these donated subscriptions, you can do so by signing up at one of the higher subscription points.

And if it resonated with you, please share this post.

Sending a big pile of blessings and goodness your way. 💕

RELATED POSTS

- Wives and Archetypes

- "A feminist reading can embrace these women as changemakers who used, simply, different tools to work with and around their situation...."

- Theology Interlude

- "In fact, we, the Jews, don’t get too fussed by the literal descriptions of God as described in the Torah."

- The Point of it All

- "'Love your neighbor as yourself: I am God.' That’s the heart. That’s the beating, living, pulsing heart of Torah."

FOOTNOTES

[1] Megillat Esther doesn't mention God explicitly

The Talmud (Hullin 193b) plays with a verse from Deuteronomy, claiming that Esther is, thus, Sekrit Code for "concealed God," since in Deuteronomy 31:18, God says God will "surely hide My face face"/hester astir panai– that אַסְתִּיר astir being a lot like אֶסְתֵּר/Esther. ↩︎