Guest Post: Queer Niddah

On Bodies and Alternate Markings of Time

This is a guest post by the wonderful Rabbi Avigayil Halpern

QUEER NIDDAH

by Rabbi Avigayil Halpern

The history of niddah, like you saw last week, is…complicated. It’s pretty easy to dismiss the whole thing as irreparably misogynist. And you’d be in good company if you did want to throw out the entire system of these halachot along with the mikveh-bathwater – plenty of thoughtful Jewish feminists and generally invested Jews have decided these laws don’t work in their lives.

But if you fall into the camp of niddah-haters – whether you’ve never encountered the idea of niddah before in your life or whether you observed these practices for years and then stopped, or if you fall anywhere in between – I want to invite you, just for next one thousand words or so, to suspend some of your HIGHLY JUSTIFIED dislike of niddah. You likely don’t know me, so I’m asking you to take it a little bit on faith: I’m a feminist! Let’s explore some niddah Torah together.

I’ve spent a bunch of time studying the traditional texts about the laws of niddah. But one of my favorite classical texts about niddah isn’t a legal one – instead, it comes from the Bekhor Shor, which is a Torah commentary written by one of the Tosafists, part of the famous school of legal interpreters of the Talmud from 12th-century France. Commenting on a verse about the commandment of circumcision (Genesis 17:11), he writes:

"And it will be a sign of the covenant between Me and you". A symbol and a sign that I am the Master and you are my servants, and the sign is sealed in a private place that will not be seen. … And since the Holy One, Blessed be God, commanded men and not women [with the obligation to circumcise the penis], we learn that the place of manhood ("makom zachrut") was where the Holy One, Blessed be God, commanded to seal the covenant. And the blood of niddah [menstrual blood] that women guard, and tell their openings to their husbands, this is to them the blood of the covenant ("dam brit").

This text, of course, makes a lot of assumptions about which body parts belong to people with which experiences of gender that I (and hopefully you, dear reader) don’t share. But what I want to highlight is that the Bekhor Shor is offering us a perspective on menstruation and observing rituals around menstruation that regards it as be part of a covenantal relationship with God.

And if we say that our bodily functions–in this case our periods–can be framed through ritual as not just even part of a sacred relationship with God, but rather part of a covenantal relationship, that means – at least to me – that we should be seeking out ways to understand these rituals, which some Jewish women have been observing for millennia in different forms, as for all of us.

My particular contribution is thinking about how niddah can be present for queer people – how we can approach our menstruating bodies as holy and relating to God in ways that reach beyond the confines of the straight, married relationships that these laws typically assume.

There is a huge amount of work yet to be done on the practicalities on this front. For example, when two people in a relationship both menstruate, how would niddah look? Folks on the ground are building this halacha (Jewish law) through their lives as we speak, but there’s so little written on it.

As this emerges, though, there is another important front for this work: how does niddah mirror and parallel the queer experience?

One way that niddah “is queer,” so to speak, is in the kind of relationship to time it can cultivate. The scholar Sarit Kattan Gribetz points out that the vaginal checks (“bedikot,” in rabbinic parlance) that the rabbis of the Mishnah imagine happening daily in a purity/impurity context were a kind of parallel to men’s daily prayer practices. The checks, which involve inserting a finger wrapped in a clean, soft white cloth into the vagina and wiping it around, confirm that there isn’t more blood hanging out internally and that a person is actually done with their period. Though today nobody’s niddah practice involves bedikot every day (MAXIMUM, some of the people who practice niddah do twice-daily checks for the week after their period, and many people do only two or three total in that week), I think her insights on the nature of the practice stand.

It’s helpful before getting to the quote itself to understand that, in traditional readings of Jewish law, women are said to be exempt from “time-bound mitzvot,” those commandments which must happen at a certain time of day, week or year, (It’s a wildly unstable category riddled with problems, but for our purposes, it is true that the Mishnah (Brachot 3:3) states clearly that women are exempt from reciting the Shma twice daily.) Kattan Gribetz writes:

“Structurally and experientially the mandate to check oneself twice daily, in the mornings and evenings each day, meant that rabbinic sources orchestrated a gendered schedule: while men pray and recite the Shema, women check their bodies…

Rituals that marked women’s time functioned to turn the female subject’s attention inward, toward the body, for the purpose of establishing or refraining from a relationship with other people and objects during times of purity and impurity. This inward orientation is very different from that cultivated by the recitation of the Shema and, in turn, the other positive time-bound commandments, in which men turn toward the celestial bodies (the sun, moon, and stars), and other external signs, to mark the appropriate times for sacred rituals and prayers, for the purpose of establishing a relationship with the divine.”

In other words, menstrual ritual – coded as “for women” – encouraged an orientation to time based on a person’s inwardly-oriented experiences of themselves and their body. In contrast, prayer – coded as “for men” – encouraged an orientation to time that was based on objective, external factors.

An ongoing challenge for feminists of all backgrounds, but which can be particularly acute for those of us who do religion, is how much to reclaim things that might be taken less seriously because they have been attributed to women and thereby devalued, versus noticing when those things are sexist and should be rejected entirely. But I think that there is something profound in rituals that focus on our embodied experiences and not some external calendar.

In an incredible piece for SVARA called “Sacred Time Travel: Crip Time, Queer Time, and Torah Time,” (please go read the whole thing immediately!) Rabbi Elliot Kukla reflects on his experiences of Torah learning in an explicitly queer and disabled context:

“Queer theorist Judith (Jack) Halberstam notes that queer time, like crip time, is less linear. In their 2005 book In a Queer Time and Place, Halberstam argues that “queer uses of time and space develop… in opposition to the institutions of family, heterosexuality, and reproduction.” Queer identity is formed by time-warping experiences like coming out, gender transitions, and generation-defining tragedies such as the AIDS epidemic.

…like the Sages of the Talmud, we have been exiled from mainstream society, and along with this painful exile comes freedom from normative notions of the clock. The Torah that we are able to nourish as queer, disabled learners was both present at Sinai and, simultaneously, has never existed before.”

In other words, queer people have an experience of time that is not driven by an external system of social expectations and convention, but by our own experiences – both those that are individual and communal. Queer time emerges from queer experience into the world, rather than the world structuring queer time.

I want to suggest that niddah observance can align with a sense of queer time.

It is an experience of time that is not based on an external, measured, “universal” calendar. Rather, it takes place in each person’s body, outside of “normative notions of the clock.”

This is an offering from the laws of niddah to all of us:

How can we experience ritual and sanctity through the timelines of our own bodies, our own experiences?

How can we connect to God not through an externally-enforced, universalizing push to sameness, but a flexible, personal – yet also potentially shared – system of sanctity?

This is but one gift looking at niddah through queer eyes can offer us. Amidst the sexism, we can find places that hilkhot niddah offer us the potential for more agency, more connection, perhaps even more freedom. And this is, potentially, why some queer couples are embracing niddah practices.

In a 2020 JTA article, several queer Jewish couples explain why they’ve adopted niddah observances and why they find them meaningful. Leana Tapnack says:

“In terms of the ways that we were raised, observant Jewish families have mikvah as part of just the way that they function generally. Even though ‘This is what everyone does,’ isn’t usually compelling to me. I did have to mourn a considerable number of dreams when I came to terms with my gay identity and as I’ve became more confident in my ability to manage both being gay, being queer and being religious on my own terms, it feels like why should I mourn things that I don’t need to mourn, things that I can reclaim, things that I can own?”

Tapnack is describing a reality of queer Jews taking back these mitzvot, embracing a relationship with them. You have encountered the “bnot Yisrael,” [the daughters of Israel] the Jewish women who – so the Talmud claims – adopted a practice that “if they saw even a drop of blood like a mustard seed they would wait seven clean days for it.” (Niddah 66a.) And yes, it’s possible that this was an attribution of a rabbinic, male stringency to women for rhetorical purposes.

But it’s also possible that this is a glimpse of a ground-up halakhic norm being created by a group who normally did not have agency to legislate for themselves. Today, this “stringency they took upon themselves” is part of the halakhic conversation – the practice adopted by those with less power became a key part of textual legal interpretation.

If, like the Bechor Shor suggests, niddah observance is part of how we can be in covenantal relationship with God, then it requires mutuality. Covenants are two-sided; God offers us ways to be in relationship with Her, and we shape those ways with our bodies and experiences.

We can’t know what niddah observance will look like for observant queer Jews yet. But we can look for moments of queerness that flash out at us from the texts, and learn from them. And we can remember that bnot Yisrael, and their practices, eventually become vital parts of hilkhot [the laws of] niddah.

What people do, which mitzvot they shape with their very bodies, becomes part of Torah.

We, too, are the texts.

Rabbi Avigayil Halpern (she/her) is a teacher and writer whose work focuses on feminist and queer Torah, most recently through her newsletter project, Approaching. She lives in DC, leading a home-centered, pluralistic, welcoming Jewish community in Adams Morgan– follow at @BaseinDC on IG and show up if you're local, and follow her at @_Ravigayil.

RDR again:

Here are a few more things:

The Trans Halakha Project

is about “empowering and nourishing the trans, intersex, nonbinary and gender nonconforming Jews whose experiences are not yet at the center of Jewish legal exploration.” And they’ve just dropped their first set of legal responsa (tshuvot) and ritual, and it’s 🔥. The tshuvot focused this year on two key gendered body practices—niddah, as we’ve been discussing these last two weeks, and brit milah, circumcision. Must a trans man or transmasc person observe niddah? Can a trans woman? If circumcision is traditionally considered a requirement for “men,” converting to Judaism, how do we navigate when issues around gender and bodies get more complex? (Answer number one: We don’t force dysphoria on people!! That’s not how holiness works.)

This includes an amazing compendium of tefillat trans: rituals and blessings for trans lives—for everything from marking gender euphoria (that feeling of gendered “rightness,” alignment, comfort), blessings for taking hormones, for marking delays and disappointments, for protection of self or community, rituals for name change and transition, and so much more.

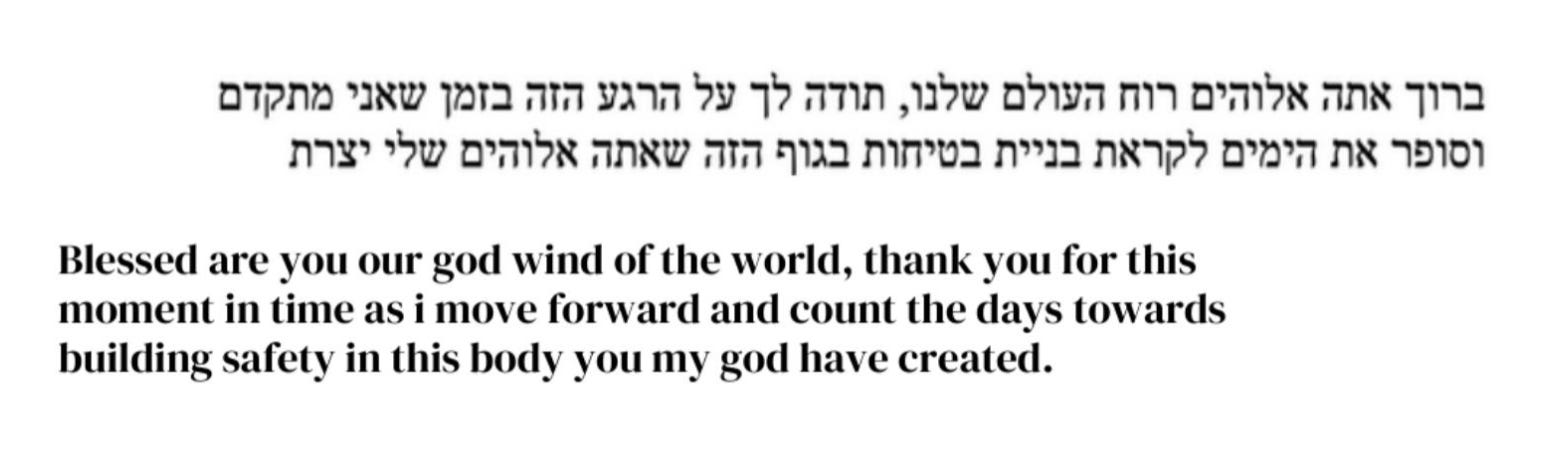

I thought this blessing, for “Marking Trans Time,” by Lieb Swartz-Brownstein was particularly on point for today’s essay—it’s meant to mark “the passage of time leading up to any form of gender affirming surgery or change, a gender affirming B Mitzvah, or any other moments of transition”:

There’s also the Queer Mikveh Project, spearheaded by Rebekah Erev. There’s also a ‘zine/Queer Mikveh Guide book. If you have capacity to pay the amount you would for a new book, click here. If you do not, click here.

Rabbi Avigay