Spy vs. Spy

Or: How Stories Tell (on) Us

This is Life as a Sacred Text 🌱, an everybody-celebrating, justice-centered voyage into ancient stories that can illuminate our own lives. It‘s run on a nonprofit, so it’s 100% NAZI FREE. More about the project here, and to subscribe, go here:

Hag sameach/chametz tov to all my hevre on the last day of Pesach! Here and here are a couple of Miraim/Song of the Sea- related pieces if you're reading this Tuesday and want to be thematic.

Today we're going to look at a story as a chance to think about, well, looking at stories.

There are a million ways we could do this, here's just one.

So, we remember from way back that there was this "we've been freed from Egypt, and now we're going to go into the Promised Land" master narrative arc in the Torah, yes?

(We've already interrogated the conquest narrative from a historical perspective. Look here for that piece. This week, we'll look at other elements in the story, since there's so much more to explore. Next week, we'll have a guest post bringing up some of these related questions again.)

So now after a number of antics– we got settled in the desert, got commanded various mitzvot, had a bit of stress around some pining for cucumbers and melons and then Miriam booted from the camp for a week after some sort of Kushite wife-related disease onset.

But now it's time to get serious.

God spoke to Moses, saying,

“Send agents to scout the land of Canaan, which I am giving to the Israelite people; send someone from each of their ancestral tribes, each one a chieftain among them.” (Numbers 13:1-2)

Yeah, OK, linking to that conquest narrative piece one more time, here.

But reps from across the community have to check out the new place. This means that they share who does the dirty work and will theoretically everyone will help build consensus from across the Israelites later on.

When Moses sent them to scout the land of Canaan, he said to them, “Go up there into the Negev and on into the hill country, and see what kind of country it is. Are the people who dwell in it strong or weak, few or many? Is the country in which they dwell good or bad? Are the towns they live in open or fortified? Is the soil rich or poor? Is it wooded or not? And take pains to bring back some of the fruit of the land.”

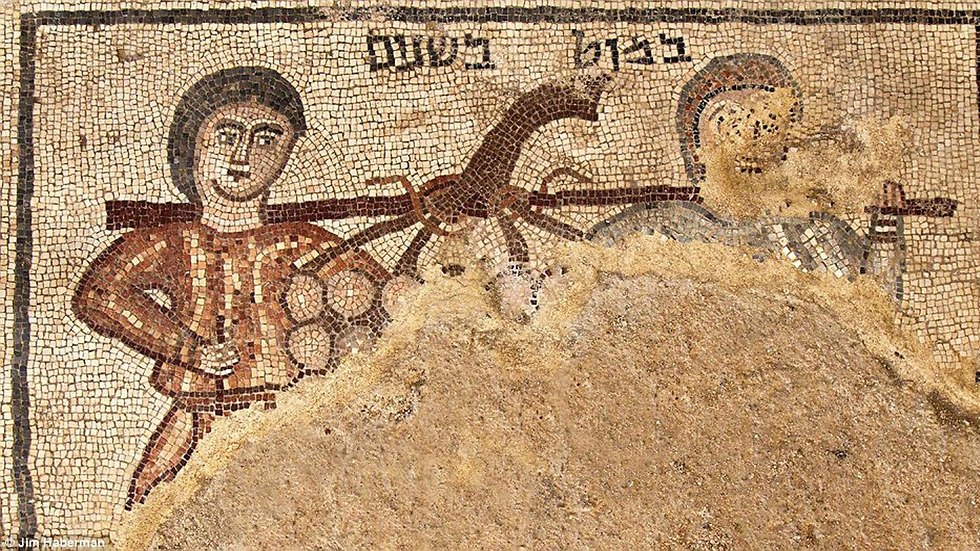

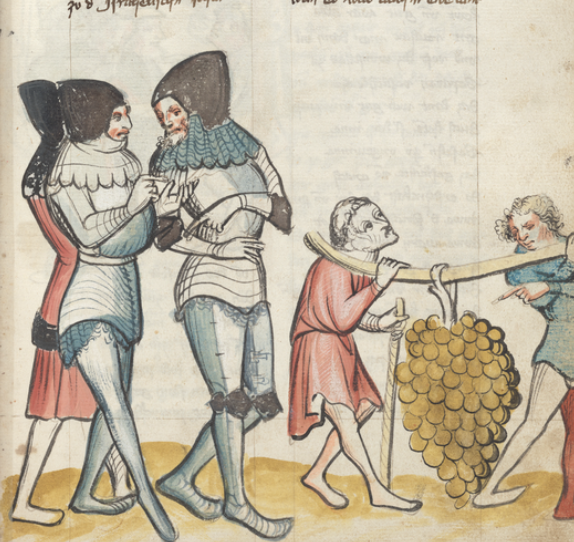

They went up and scouted the land, from the wilderness of Zin to Rehov, at Levo-hamat. They went up into the Negev and came to Hebron, where lived Ahiman, Sheshai, and Talmai, the Anakites.—Now Hebron was founded seven years before Zoan of Egypt.—They reached the wadi Eshcol, and there they cut down a branch with a single cluster of grapes—it had to be borne on a carrying frame by two of them—and some pomegranates and figs. (Numbers 13:17-23)

People lurrve illustrating this part.

Ginormous produce! Whoo!

Whoo??

At the end of forty days they returned from scouting the land. They went straight to Moses and Aaron and the whole Israelite community at Kadesh in the wilderness of Paran, and they made their report to them and to the whole community, as they showed them the fruit of the land. This is what they told him: “We came to the land you sent us to; it does indeed flow with milk and honey (1) and this is its fruit. [*gestures towards megafruit*]

However, the people who inhabit the country are powerful, and the cities are fortified and very large; moreover, we saw the Anakites there. [Anak means "giant" in Hebrew.] Amalekites dwell in the Negev region; Hittites, Jebusites, and Amorites inhabit the hill country; and Canaanites dwell by the Sea and along the Jordan.” Caleb hushed the people before Moses and said, “Let us by all means go up, and we shall gain possession of it, for we shall surely overcome it.” But the other men who had gone up with him said, “We cannot attack that people, for it is stronger than we.” Thus they spread calumnies among the Israelites about the land they had scouted, saying, “The country that we traversed and scouted is one that devours its settlers. All the people that we saw in it are of astonishingly great size; we saw the Nephilim, and we looked like grasshoppers to ourselves, and so we must have looked to them.”

Joshua and Calev want to go attack, but the other ten scouts aren't so sure. They say, look: We saw giants, we saw a bunch of other peoples occupying other parts of the land, and then we saw these people mentioned in Genesis 6:4 as the offspring of divine beings and humans!

As a result, a bunch of the rank and file Israelites start whinging yet again about how had they died in Egypt or if they'd die in the wilderness– well, that'd be better than getting stabbed by scary dudes, and God loses God's non-anthropomorphic temper yet again, and says, fine. You will get what you're asking for.

‘As I live,’ says God, ‘I will do to you just as you have urged Me. In this very wilderness shall your carcasses drop. (Numbers 14:28-29)

The Israelites: 😶

Everyone who was counted in the census in the beginning of the Book of Numbers– everybody age 20 and up– will die before they get to the Promised Land, somewhere in the "as of right now we're officially cursed to wander in the desert for 40 years" portion of our program. All the y0ungsters and kids-to-be will get in.

"You kept begging to die in the wilderness rather than do this hard thing? OK!"

How can or should we understand this story?

As we say, there are 70 faces of Torah.

Let's have a look at what we can glean from turning this story around and around– and how this can be a case study for thinking about what else we sometimes communicate– consciously or not– with our interpretations.

As can all tales in Torah, this can be a message about obedience. It, for better or worse, can deliver an authoritarian model of Judaism (or Christianity, I reckon)– one in which failure to follow God (and, presumably, your religious leader, God's emissary here on Earth), engenders fatal consequences:

"People didn't trust God enough to go along with God's plan even when they were scared so they were punished."

Implied: You must follow my instructions if you would like to be Good, Safe.

There is the reading that tries for a trauma-informed lens, that seeks a more compassionate rationale for such a harsh divine decree. Something like:

"After their whole lives enslaved, the generation that participated in the Exodus– which was traumatic enough, jeez– wasn't emotionally ready to do the next step of setting up a new, just society. They regarded themselves as inferior to others– it was their low self-esteem that caused them to regard themselves as 'like grasshoppers' rather than as empowered as full people. They couldn't have handled the responsibility of creating something new in the Promised Land. God finally recognized that and realized that only people who had grown up knowing freedom could best set up the future." (2)

It certainly puts a lot of pieces of the puzzle together, and its heart is certainly in the right place. (I've used this line of thinking many times over the years, I confess). But it runs the risk of falling into a paternalistic trap– after all, many profoundly oppressed and traumatized people throughout history have been extraordinary agents for leading their own way not only to freedom, but towards the creation of a new world on the other side, who have proven on their own terms that dying in the wilderness is not the only possibility.

Implied, consciously or not: Only healed people can be leaders.

(Needless to say: We're all works in progress– and the most dangerous people are the ones who won't admit this, whether it's because they don't think they have any work to do or because they think they're not supposed acknowledge it because they're a Spiritual Leader.™)

Cantor Josee Wolff actually locates the problem in Moses' original binary framing of the spies' mission. Remember? Moses instructed them to check out:

Are the people who dwell in it strong or weak, few or many? Is the country in which they dwell good or bad? Are the towns they live in open or fortified? Is the soil rich or poor? Is it wooded or not?

She wonders whether more

"open-ended questions would have led the scouts to bring back a a different report. At least these sorts of instructions might have given them more room to develop their own stories in a less dualistic fashion."

Here, we understand that the problem may have been that the scouts were forced to think in an either/or way– and, perhaps, in an us/them way. An all or nothing way. That perhaps if the spies had been given more open-ended questions, they would have been able to see the situation more holistically, and reflect about the challenges upon them more thoughtfully.

However, given binary questions, they provided binary answers. Are the people strong or weak? Strong. Are the cities open or fortified? Fortified.

Implied: There may be more than one "right answer" to a complex situation! Binary thinking limits our liberatory imagination! Leaders bear huge responsibility for the success of those on the ground, and if the latter fail, it's likely the responsibility/ failure of the former!

And what if the ten scouts were offering an accurate account of their experience? And what if they were being told by authority figures to ignore their take on the situation, because it didn't conform to the agenda of those in power?

And again, we over here at Life is a Sacred Text Inc. are open to looking at God, in these stories, as a literary figure with whom we can engage with curiosity-- and assume that doing so doesn't necessarily validate or disprove or anything about anyone's experiences of the living divine, or even about how Torah can engage with those experiences. Theology, and God, can be big enough to hold all of it.

What if we were willing to question all of our assumptions about who's right and who's wrong, just to see what might happen if we opened the story from the other side?

What if God and Moses were ready to launch Project Promised Land but their folks on the ground told them that it was, in fact, unsafe?

And if there were a couple of people willing to say what those with power wanted to hear, but the majority of voices– those warning against taking action were speaking not from warped perception, but actual concern?

How many times have experts warned that an outcome is not right, and been steamrolled or ignored, because a little truth happens to be inconvenient at the moment?

How often have those most impacted warned that an organization is not safe, to no avail? How often have people with some power– but lesser power– tried to speak out, and been punished for doing so?

And then derided as the narrative is fixed to paint them as the cowards or the troublemakers, not the brave heroes willing to comply with power's agenda?

It happens all the time.

What if we assume that the spies aren't working in bad faith? We could even posit that Promised Land 1.0 didn't, in fact, release at that time, so we will never know how it would have gone– and it's possible that it would have been a disaster, just as those ten spies warned us that it would have been?

What if God– or whoever was writing this story after the fact– even recognized this and used this 40 years "punishment" as a cover, so that time could be bought without making authority look bad?

Implied: History is written by the victors, and we must ask why the stories we have are written the way they are– including who is blamed, and why.

We can also look at the Biblical Criticism model– the notion that the Torah that we have now is likely a composite of several different authorship strands who have different agendas and perspectives– to try to make sense of the story.

Hebrew Bible Professor Jaeyoung Jeon suggests that

The scouts' mission took them as far as the Valley of Eshcol, which marks the southern border of Yehud, probably created by the demographic division in the fifth century BCE. The scout narrative can be read as an explanation of the situation at that time, that is, to explain why Judah had lost the land south of the valley. The passages relating to Caleb and Hebron were added even later to the scout story probably as a territorial claim for the Hebron area in the time when the Persian Empire was making the border adjustment in the late fifth or early fourth century BCE.

That is to say, a story about geography and borders is used to explain things about geography and borders.

Implied: Stories can be used to backdate, explain, validate a current political reality, (as we saw with the earlier use of the conquest narrative.)

This, as all of these, is really a story about power, and who has it, and how, and why– and where one locates oneself in the story depends on where one locates oneself vis a vis those questions.

Of course, there are so many more possible readings! We could be here all day, and a few more days after that!

For example– it's notable that there are a lot of parallels between this story in Numbers 13-14 and the story of the Golden Calf in Exodus 32, especially Numbers 14:13-20 next to Exodus 32:11-14.

What are we to make of this? What conclusions should or could we draw? And what might be implied by any version of the story we might tell?

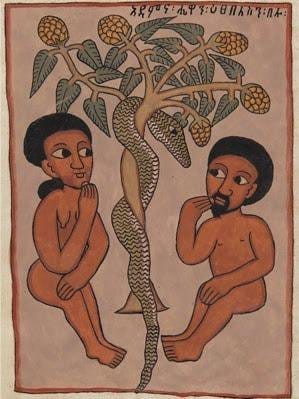

We see the spies carrying this heavy, gorgeous, perfect fruit from this perfect land back to the people, echoing the fruit that Eve gave from Eden, from this one tree, to Adam. What's learned? Or not? And what could we draw out from this parallel– and what would it tell about us as we did?

Every story we tell – and every way we tell a story– reveals something about us, whether we are aware of it or not.

The only question is whether or not we're willing to be reflective about what we're putting out– and what our listeners might be hearing when we tell it.

Like this? Get more of it in your inbox every week. 🌱

For free every Monday—sign up at the ‘Subscribe now’ button just below.

And if you become a paid subscriber, that's how you can get tools for deeper transformation, a community for doing the work, and support the labor that makes these Monday essays happen.

A note on the subscription model:

I want my work to be as accessible to as many people as possible, in as many ways as possible. That's why the Monday essays are free, and why we donate subscriptions to anyone for whom paying is a barrier to the House of Study posts.

I also believe people should be paid fairly for their work. Needless to say, these two values sometimes seem to be in conflict, but I do what I can to find a fair balance. I offer many resources for free, and charge for others. When you donate generously or pay at the top of our scale, that helps support the work I do, provides access for those who have fewer resources, pays for the infrastructure and the technical and practical support that it takes to do this, and helps us keep the work sustainable.

And as always, if you want in to the Thursday space but paying isn't for you now, just email support@lifeisasacredtext.com and we'll hook you up.

And if you’d like to underwrite one of these donated subscriptions, you can do so by signing up at one of the higher subscription points.

And if it resonated with you, please share this post.

Sending a big pile of blessings and goodness your way. 💕

FOOTNOTES

[1]Land flowing with milk and honey

[2]Traumatized Israelites weren't ready to enter the land

Fun fact: it was probably goat milk and date honey. Which is amazing, by the way. ↩︎

I'm not going to go through and list every single one of the traditional commentators and their takes on this story, because we'd all be here forever (and a lot of them, fundamentally, line up with the first one-- the disobeying God one-- but have interesting takes on various angles of the thing, unsurprisingly.) But Maimonides kind of lines up with take two, though he was less interested in the trauma angle than seeing this as God's intentional idolatry detox:

"It is contrary to a person's nature to suddenly abandon all the different kinds of Divine service and the different customs in which they have been raised, that they were considered as a matter of course; it would be just as if a person trained to work enslaved with mortar and bricks should interrupt their work, clean their hands, and at once fight with real giants/Anakim. It was the result of God’s wisdom that the Israelites were led about in the wilderness till they acquired courage....besides, another generation rose during the wanderings that had not been accustomed to degradation and slavery." (Guide for the Perplexed 3:32). I just thought that was interesting, and this gif is basically me when it comes to Rambam anyway.) ↩︎