Tattoo Jew

Yids and Tats, Let's Talk About That

This is Life as a Sacred Text 🌱, an everybody-celebrating, justice-centered voyage into ancient stories that can illuminate our own lives. It‘s run on a nonprofit, so it’s 100% NAZI FREE. More about the project here, and to subscribe, go here:

Happy 2025! Hope you're starting off with a bang. Time for us to get back to Deuteronothings:

CW: Passing mention of cutting/self-harm

People often talk about how tattoos are unquestionably verboten in Judaism, or how you can't get buried in a Jewish cemetery if you've got a tat.

And though the discourse isn't as intense as it once was, it's timely in terms of our voyage though Deuteronomy, so today we're going to mythbust around a once-taboo subject.

Plus, you may have noticed by now– I love art of all kinds. And though I remain, to date, ink-free (minus occasional futzing with those better-quality temporary jobbies), this is a great excuse to look at some fabulous, funny, and fascinating examples of Jewish body art.

I know some of you have strong visceral reactions to this topic and these images. This is, if nothing else, a great place to do some awareness work on a lower-stakes issue, to look with curiosity and interest at your immediate emotional and intellectual responses, to slow down and ask yourself questions, to remember that we do not have to be our gut reactions. Which is not to say that you have to agree with me in the end (though hey, you might learn stuff!) Just that knee-jerk reactions aren't where any of us need to stay.

So let's begin:

You are children of God your God. You shall not gash yourselves or shave the front of your heads because of the dead. (Deuteronomy 14:1)

What do you notice right away?

The plain meaning of this verse is about not gashing yourselves... because of / for ... the dead. As a gesture of mourning. Which, obviously, was a custom back in the day. (Every sign has a story, as we say.) In emotional pain, people would do things to externalize that, to mark the moment with physical pain. To manifest irreparable loss on the body.

"You shall not make gashes in your flesh for the dead" - This was the practice of the Amorites (a general term for non-Jews) to make cuttings in their flesh when someone belonging to them died. (Rashi on Leviticus 19:28:1-2)

We know all about that now.

Dr. Janis Whitlock, founder and director of the Cornell Research Program on Self-Injury and Recovery at Cornell University, noted that

“The data suggests a neurological link between the perception of physical pain and the perception of emotional pain — where there is a spike and drop in one, there may be a spike and drop in the other,”

Though I wonder. How could you know, when you're grieving the loss of your beloved, when to stop? How could you know how to stop??

This is in part why self-harming is so dangerous. Why physical pain can't solve for the hurts in your heart.

(It should be noted that for the Jews, we have a practice that dates back as far as the Torah– in the Book of Genesis– and the Hebrew Bible– in II Samuel and Job– that upon hearing of an important death, we tear our clothes instead of our body.)

Notably, though, this prohibition in Deuteronomy is explicitly about not making cuts in your body as a mourning practice.

Golems Golems Everywhere! Clockwise: Romantic golem in a tree, gazing at the moon; pizza-noshing golem; flower-toting golem with EMET on the chest; Furby golem with blue eyes and EMET on the forehead, all by sian_shine.; Philly Gritty Golem in bright orange shag and a bright smile with EMET on his black ski cap by Amelia Moore.

But, famously, this prohibition was extended in Jewish law to include other kinds of incisions as well. Specifically:

"Or incise any marks on yourselves" - i.e. a writing engraved (more lit., dug into) and sunk into the flesh and which can never be erased because it is pricked in with a needle and remains black forever. (Rashi on Leviticus 19:28:1-2)

Which leads to Jewish prohibitions against getting tattoos, right? Right??

Enter Maimonides, generally a pretty conservative voice on Jewish law:

Writing a tattoo that's discussed in the Torah is about making a scratch on the flesh and filling the place that one scratched with eyeshadow, ink, or any paints that leave a mark. This was the practice of idolaters who [permanently] marked themselves for the sake of their idol worship. Basically, [they understood this to be] that they are likened to servants sold to the idol and marked to serve it.

When one makes an mark with one of the marking things [listed above] with a scratch/incision anywhere on the body, the punishment of lashes is carried out, [whatever their gender].... To whom does this [prohibition] apply? To the one who is writing, but the one whose flesh is written on and tattooed upon is not liable unless they helped in order to do the deed. But if they didn't do anything, they're not lashed. (Maimonides, Mishneh Torah: Laws of Idolatry 12:11)

So– these idolaters do this tattooing thing, so we just shouldn't. (Also, we learned a bunch about 12th c. tat methods there, didn't we? Eyeshadow! Or, given that we're in 12th c. Egypt, possibly: Kohl? Unclear.)

And one who does the tattooing thing has transgressed Jewish law! And one who shows up to their tattoo appointment, just lays there, says ow! a bunch and drinks water while someone else zaps a needle all over their skin (as you can see, I am very much an expert in this process from watching some tiktoks over the years) and pays is... uh... oh.

Possibly not liable at all. Not... regarded as having transgressed Jewish law in the slightest. Huh.

Maimonides was a very straightforward dude. If you did something wrong, you faced consequences. So no lashes, here, means something.

(Maimonides and I get along great on some ideas, part ways on others, and whew disagree on our concepts of punishment, needless to say.)What does it mean to have "helped the tattooer," though?? A crack so big you could drive a truck though it. Maimonides was usually agonizingly thorough in his thinking, so presumably if he meant something other than the obvious– helped the tattooer with the application of the tattoo– he would have said so, no? But he did not say that.

I'll note that here, as throughout the literature, the word used repeatedly for the act of tattooing is "writes," which causes the question to be raised elsewhere in the literature: Is the problem only with words? Are just images maybe OK? Or..?

The Shulchan Aruch, the other authoritative source for Jewish law, agrees with Maimonides' take, and defines tats pretty much the same way (so I won't repeat it) and also uses the verb for giving a tat as "writing." And says,

If one does this on another's flesh, the one to whom it was done is exempt [from punishment] unless they assisted in it. (Shulchan Arukh, Yoreh De'ah 180:2)

So again, this comes down to the tattooist's relationship to Jewish law, not the tattooee's, evidently!

Nonetheless, you find contemporary writers interpreting these words (pretty straightforward translations, these) quite... liberally, one might say.

For example, one author, citing exactly the same sources you just saw (and I promise that I'm not hiding secret other information from you), described them as such:

Maimonides... states that if the tattooed person was unaware or had no part in making of the tattoo, then he or she is not culpable. Shulchan Aruch agrees, and rules that if the person that receives the tattoo had no part in it, then he is not guilty at all. But if he or she helped in the process in any way, or asked that it be created on his or her body, then both the person receiving the tattoo, as well as the person making the tattoo are guilty.

Those are a lot of very specific conditions to derive from... "helped," I am just saying. I did not see "unaware," or "asked to be created," anywhere in those words.

Yes, later commentators ran with Rashi and talked about the sanctity of the human body, how God lent us this meat suit and we need to be careful with it and etc.

The majority of Jewish law (especially post-Shulchan Aruch) rules that tattoos are explicitly forbidden.

But– disingenuous claims like the one I just cited don't sit well with me, you know? I read Maimonides, I read the Shulchan Aruch, and I do my best to be honest about what I see.

When Ashkenazim Ashkenazi, they Ashkenazi HARD. Tats include (clockwise) a knish line tat, a pickle mezuzah curved in bright greens and a big Shin ש on it (both by Sian_Shine). Zabar's babka!!! by Evelyn Wang, matzah ball soup by Noa Margalit. Bashert, the Yiddish word for soulmate, fate, destiny, by Tahini.jpg

And lookie over here, at this earlier mishnah!

With regard to one who tattoos their skin, [if] he they a mark [an incision in their skin] but did not tattoo in it [that is, did not fill it in with ink, or] tattooed in it [that is, made ink marks on the surface of the skin] but did not make a mar [so that the process of tattooing was not completed] – they are not liable [aka they have not transgressed Jewish law]. One is liable [only] when they mark and tattoo with ink or eye paint or anything that leaves a [permanent] mark. Rabbi Simon ben Judah says in the name of Rabbi Simon, 'One is liable only when they write the name of God,' as it is written in the Torah, in Leviticus 19: Do not incise any marks on yourselves: I am God." (Mishnah Makkot 3:6)

And then the Talmud unpacks Rabbi Simon's statement:

Rav Aḥa, son of Rava, said to Rav Ashi: Is Rabbi Shimon saying that one is liable only if they actually inscribe the words “I am God” in their skin? Rav Ashi said: No, he is saying as bar Kappara teaches: One is liable only if they inscribe a name of an object of idol worship, as it is stated: “And a tattoo inscription you shall not place upon you, I am God,” which means: Do not place an idolatrous name on your skin, as I am God, and no one else. (Talmud Makkot 21a)

Indeed, the Tosefta, an earlier source contemporaneous with the Mishnah:

And one is not liable (for punishment) until one writes and incises with dye or blue for the purpose of idol worship. (Tosefta Makkot 4:15)

Here, it would seem, at least, that the prohibition is on tattooing for idolatrous purposes? With, potentially hedging one's bets viz. R. Simon b. Judah, not writing the Tetragammaton (God's most sacred Name) on oneself, either?

The left image says "Shalom Bayit," -- peace in the home-- as two dreamy figures with purple hair and closed eyes light Shabbat candles with their singular hands, each depicting the hamsa / hand with an eye to ward off the evil eye, and a challah in the middle; the middle piece depicts a synagogue or schoolhouse with flames behind it-- either those connoting spiritual power or those portending disaster-- featuring the words Yashar koach-- "forward with strength," aka well done, "to celebrate Jewish strength and resilience." The right image has a red fish in in a semicircle with semicircle detailing, echoing medieval and later depictions of the Leviathan, the primordial sea monster on whom the righteous will dine in the Messianic era. and the word inside the Magen David /Star of David in the middle is chai, life. By Tahini.jpg

The work of Omri Goldzak: Left-- Overlapping hands with calligraphy from a Leah Goldberg poem: פְשׁוּטִים וּפְשׁוּטִים הַדְּבָרִים וְחַיִּים, וּמֻתָּר בָּם לנִגְעַֹּ, וּמֻתָּר, וּמֻתָּר לֶאֱהֹב "And the things will be simple and alive, and it is permitted to touch them, And permitted, and permitted to love." Middle: A gigantic calligraphic alef, א, the first letter of the alphabet and also representative of Ain Sof, infinity, the oneness of the divine, the first word and thus the totality of the Ten Commandments (and thus sometimes Revelation) and all sorts of other good things; Right: My friend Jen's shoulder, reading Ometz Lev, courage. Jutt

Biblical historian Aaron Demsky of Bar-Ilan University suggested in Encyclopaedia Judaica that non-idolatrous tattooing may have been permitted in biblical times. He cites verses like

“One shall say, 'I am God's,' Another shall use the name of 'Jacob,' Another shall mark his arm 'of God' And adopt the name of 'Israel.” (Isaiah 44:5)

and

"Is as a sign on everyone’s hand/That all may know God’s doings" (Job 37:7)

and

“Surely I have graven upon your palms: your sealings are continually before me” (Isaiah 49:16).

He also notes that those enslaved by Jews in Elephantine were marked with the name of their owner, as was the general practice.

Of course, we don't know for sure whether those verses were intended to be literal or metaphorical.

It should also be noted that there is at least one Jewish culture with traditional tattooing practices– the Beta Israel community of Ethiopia.

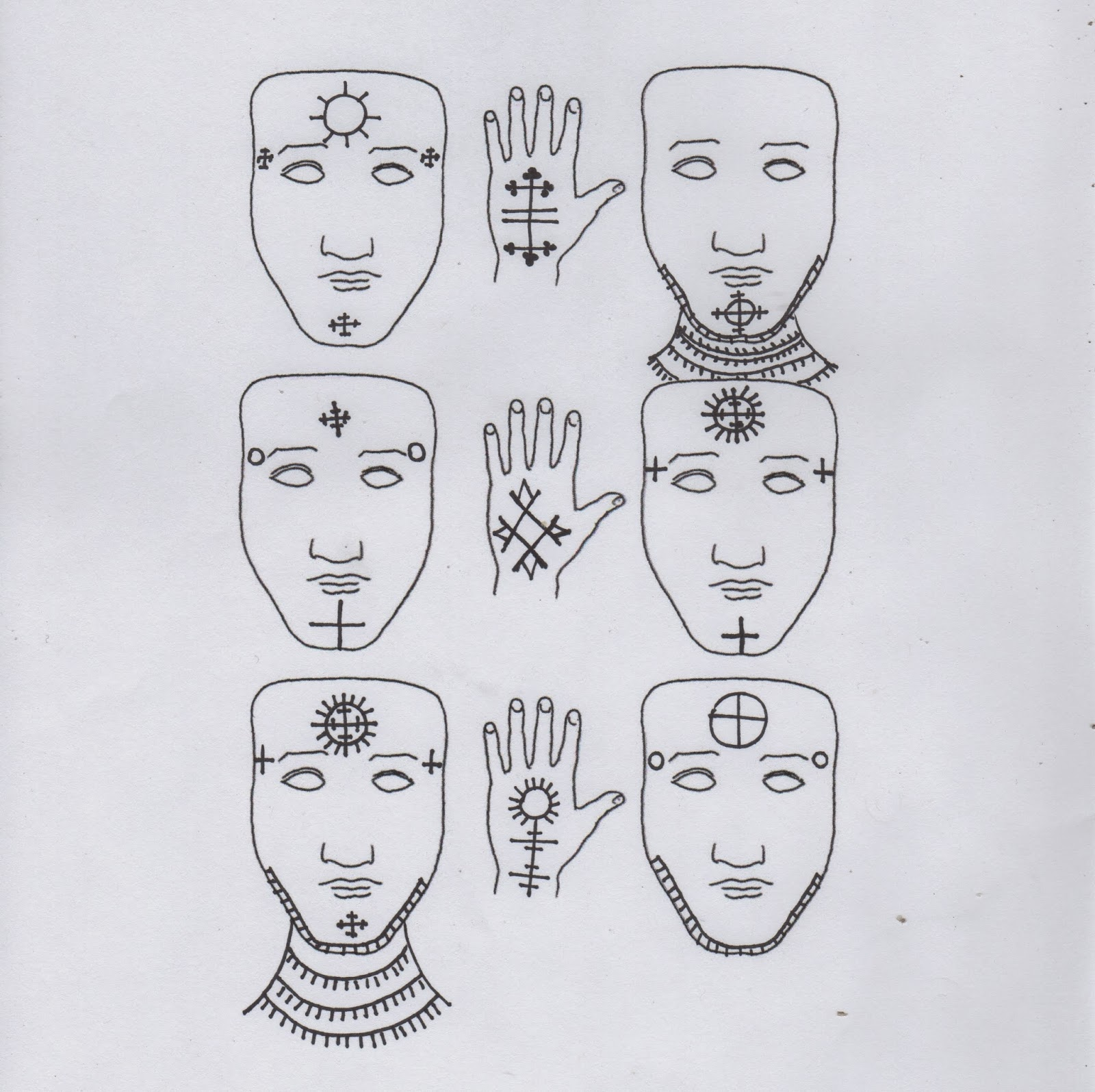

Photos of Beta Israel women photographed by Professor Noam Sienna in 2010 in Jerusalem, and notes on Beta Israel tattoos from Sienna's field notes, shared on Sienna's old blog. L: A Black woman with short dark hair, and a blue tattoo running from her ear along her jaw to her chin and, presumably, around the other side-- and down under her chin. We see three lines running in this parallel track, with shorter lines going perpendicular up from the uppermost long line, and down from the second long line. It is difficult to tell from the angle of the third long line what might be present there. The R photo is of a Black woman in sunglasses and a white haircovering with five visible blue lines running across her neck, with shorter lines running perpendicular downwards from each of them. The Center image shows six face drawings and three hand drawings with a number of markings of various Beta Israel tattoo styles.

Beta Israel tattoos are known as tukurat. As Professor Noam Sienna, a scholar of Jewish culture and history, notes, those who say things like, "Jews don't get tattoos," are, consciously or unconsciously gatekeeping.

As Sienna puts it,

What would it mean to consider seriously what Beta Israel tattoos could represent as a Jewish practice? At the very least, it would mean foregrounding the diversity of embodied Jewish experiences in our discussion of what ‘Judaism’ is.”

Rabbi Sharon Shalom writes in From Sinai to Ethiopia: The Halachic and Conceptual World of Ethiopian Jewry,

In Ethiopia, girls customarily had images tattooed on their faces, on the forehead or neck. Some even chose the sign of the cross. To the outside observer, this phenomenon seems particularly contemptible...Still, the women continued to do it. Why? And why was the issue of tattoos so important in Ethiopian culture? I have found several explanations for this:

Protection from the evil eye: people believed that the tattoo had the power to deflect evil spirits.... Cross symbol: religious and cultural reasons...Some say that the Ethiopian Jews did this out of awareness and intent, in order to make it difficult to distinguish them from the Christian population. Some, however, say it is a matter of interpretation, and that the biblical commandment “You shall not make any cuttings in your flesh for the dead, nor imprint any marks upon yourselves” (Leviticus 19:28) was intended only for men. I do not intend to rule on this issue.

"I do not intend to rule on this issue." Nine words that carry worlds from a rabbi straddling both common rabbinic understandings of Jewish law and his own community's longstanding culture and practice (and whatever his own private feelings on the matter may be.) Earlier in this section he acknowledged that Jewish law was not on the side of tattooing– but, he said, he was gonna sit this one out.

It's possible that there may be other Jewish cultures with tattooing traditions; I'm hardly an expert on every Jewish practice worldwide. I'd be glad to learn if you know something I don't!

Left: A bearded man in black with a white undershirt, in a pose of sleeping on one hand, while holding himself up with the other, with some foliage behind him, rendered in realistic tones, with the word "Vayetze"/ויצא at the bottom. By Daniel Mizrahi. R: Sam Solomon got the print of Yosl Cutler's woodcut illustration from Moyshe-Leyb Halpern’s collection of poems, Di goldene pave/ The Golden Peacock, artist unknown. A black and white illustration of a seascape, with a sun depicted radiating lines, in a heavy Constructivist style. Im

And, of course, the Nazis engaged with the Jewish prohibition and stigma against tattooing in ways that were both dehumanizing and horrific. But there has also been a trend, as we enter the last years for most survivors, of some grandchildren, and even children, getting their relative's number tattooed on them, as a way to honor them, their strength and resilience, and everything they endured.

Of course, this is sometimes met with disbelief or outrage– why would anyone choose to replicate the horrors of the Nazis?? Or: Isn't this some sort of provocative virtue signaling talking piece?

But the family members interviewed in the handful of pieces I've read on the topic all seem to either speak specifically to the horrors that their beloved family member endured, to their obligation to never forget, to their love of this specific person and what the number means to their personal history, their life.

L: A grandmother's arm, with her grandchild's tattoo with the same number and the words "Never forget" in Yiddish underneath. Middle: Amir, a bearded white twentysomething, Oded, a bearded white man with white hair, in his fifties, most likely, Livia Ravek, an elderly white woman, and Daniel Philosoph, a bearded white man in his twenties, all stand with their arms clasped, with their shared tattoos visible-- the Auschwitz concentration camp number 4559 on their inner forearms. R: Orly Weintraub Gilad has her grandfather's Auschwitz number, A-12599, tattooed on her arm, with greenery interspersed. You can see the side of her jeans and the inner part of her arm visible; she, too, wears the number on the upper part of her inner arm.

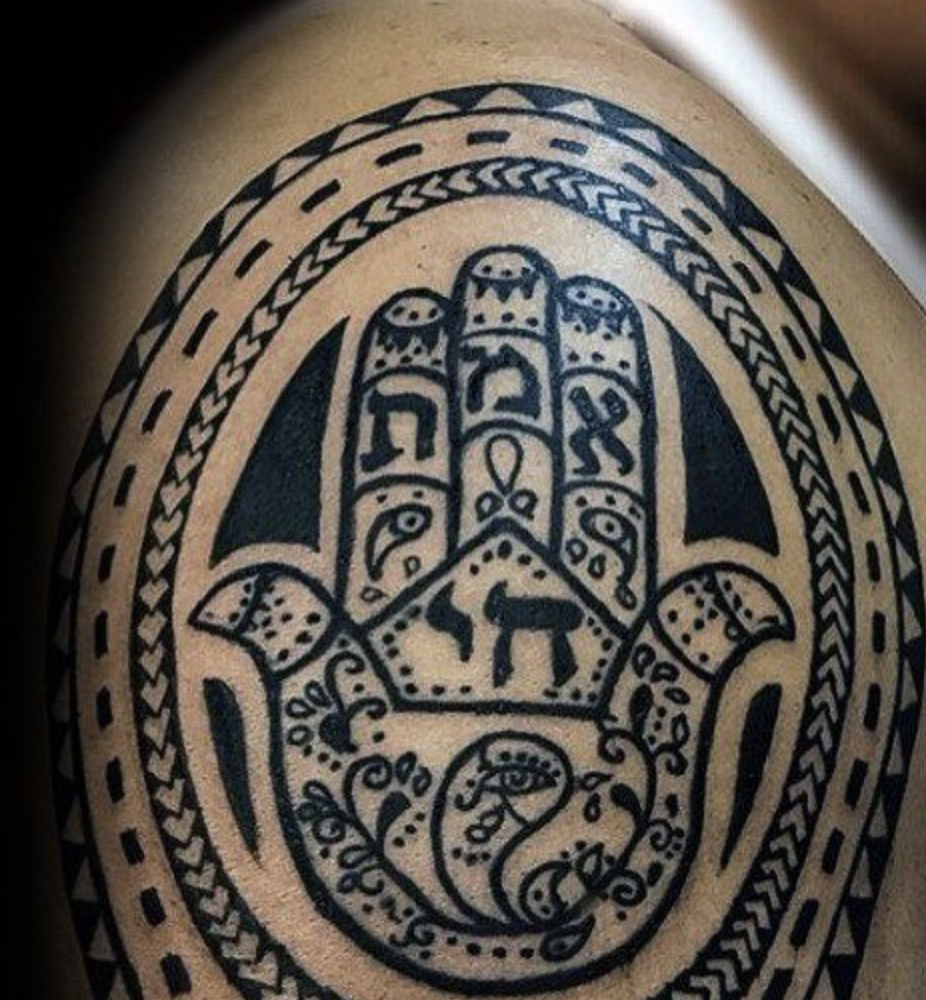

And of course there are a bevy of hamsot, to ward off the evil eye. Here are just a few--the first has a traditional blue round eye to ward off the evil eye in the center, surrounded by pink and lavender flowers, a Star of David right above it, and just above that, in the middle finger, a fish, representing the Leviathan upon which the righteous feast in Messianic times. Artist is Anna at Halo in Greensboro, NC. Next (Clockwise) is a Star of David, Chai/חי/life, and henna-like swirls and highlights of orange, blue, green and red by Ann Palmer. I unfortunately don't have the name of the artist who did the elaborate shoulder piece with Chai in the middle and Emet /אמת/Truth on the index, middle and ring fingers, with henna swirls and little eyes buried in the design, with a circular border of strong arrow shapes, with a ring of dotted lines around that, finished by a triangular border serving as the outermost ring. Blue hamsa with orange border and flower details, chai with circle and flowers, orange eye in the middle, and dots, by Peter Skidmore. Hamsa in dark teal, filled with teal and yellow, and floral and sun motifs, including small pink flowers and green leaves with a big blue eye in the center by Shira Sterling. And, of course, how can we pass up the sacred, traditional form: "old 90's tattoo coverup hamsa," elegantly burying that fading tribal design in a new, fresh protective hand with additional henna-like details by Noah Offitzer.

Yes, yes, piercing is uncontroversial

People of all genders wore earrings:

Aaron said to them, “Take off the gold rings that are in the ears of your wives, your sons, and your daughters, and bring them to me.” (Exodus 32:2)

Rebecca had a nose ring:

"I inquired of her, ‘Whose daughter are you?...And I put the ring on her nose and the bands on her arms.” (Genesis 24:47)

As did other women:

I decked you out in finery ....I put a ring in your nose, and earrings in your ears... (Ezekiel 16:11-12)

And Rabbinic Judaism co-signs, for example, after piercing, before they're ready for Big Girl earrings, on Shabbat:

Girls may go out with threads or even chips in their ears [and it's not regarded as "carrying"]

Because holes could close up and were thus "less permanent?" That's what I was always told. But as you've seen, above, it may not be so cut and dry.

Some beauts by Sian_Shine; if Baba Yaga's house was a pomegranate (pomegranates are Jewish symbols; they're all over Jewish (especially Biblical) texts, we talk about how there are 613 seeds for the 613 mitzvot, etc etc; Heneni ("here I am") in amazing medieval animal illuminated lettering. And I was just required to include this hyperrealistic Kedem grape juice bottle, OK??? By Gab Yunis.

"But what about getting buried in a Jewish cemetery"?

Yeah, that is, as they say, a bubbe meise, an old grandma's story. Not true, no basis in fact.

Where did it come from? Well, probably the fact that the Mishnah (Sanhedrin 6:5) talks about not burying certain sinners together with the regular folks– but that meant, like, people who died as a result of the very, very stringent capital punishment process at the hands of the Sanhedrin. Not regular folks who did one thing that wasn't on point– because that would be... everybody?

But back in the day, getting a tattoo was regarded as a horrific scandal, and certainly an imitation of the ways of the non-Jews, and lots of people might have said things like that to scare people away.

And, sure, it's always been true that Jewish cemeteries can make whatever rules they want about who gets buried where. BUT.

What are they going to do?? Decide that getting ink in the skin is a greater sin than a whole long list of things that a person can do that aren't apparent to the visible eye?? Say that Holocaust survivors aren't permitted in their Earth?? Decide that– if they're running on the "this is a sin" perspective– they know who did tshuvah (repented sincerely) about their tat and who didn't??? And more than that– there's a tradition that death atones all sins. (Maimonides Laws of Repentance 1:4).

Basically: I've never heard of a cemetery not taking a Jew because of their ink.

(And no, Jews by choice don't have to get their lasered off to convert, either, don't worry.)

So. This is a lot of information! What do do with it? I don't know!

But, as they say: Knowledge is power, even if ink is forever.*

*-ish? Laser removal has become increasingly effective, from what I hear?

🌱

Like this? Get more of it in your inbox every week.

For free every Monday—sign up at the ‘Subscribe now’ button just below.

And if you become a paid subscriber, that's how you can get tools for deeper transformation, a community for doing the work, and support the labor that makes these Monday essays happen.

A note on the subscription model:

I want my work to be as accessible to as many people as possible, in as many ways as possible. That's why the Monday essays are free, and why we donate subscriptions to anyone for whom paying is a barrier to the House of Study posts.

I also believe people should be paid fairly for their work. Needless to say, these two values sometimes seem to be in conflict, but I do what I can to find a fair balance. I offer many resources for free, and charge for others. When you donate generously or pay at the top of our scale, that helps support the work I do, provides access for those who have fewer resources, pays for the infrastructure and the technical and practical support that it takes to do this, and helps us keep the work sustainable.

And as always, if you want in to the Thursday space but paying isn't for you now, just email support@lifeisasacredtext.com and we'll hook you up.

And if you’d like to underwrite one of these donated subscriptions, you can do so by signing up at one of the higher subscription points.

And if it resonated with you, please share this post.

Sending a big pile of blessings and goodness your way. 💕