Ten, Again

Tellin' 'Em What They've Been Told

This is Life as a Sacred Text 🌱, an everybody-celebrating, justice-centered voyage into ancient stories that can illuminate our own lives. It‘s run on a nonprofit, so it’s 100% NAZI FREE. More about the project here, and to subscribe, go here:

As Moses stands on the edge of the Jordan, telling the Israelites about everything that's happened on their long strange trip, it's unsurprising that he revisits the thing that would define them, and us as a people, from then forward.

I mean:

Has any people heard the voice of a god speaking out of a fire, as you have, and survived? (Deuteronomy 4:33)

I love that this phrasing drives home the parallels between the terrors at Sinai and Moses' own (far from cuddly) experiences at the Burning Bush. A lot of directions to take that observation, needless to say.

But today, we're here to look at Moses' retelling of the Ten Commandments, known in Jew as Aseret ha-Dibrot, the Ten Words, and sometimes known as the Decalogue (from the Greek deka logoi– the... ten words).

The Deuteronomy version is phrased a little differently than it was in Exodus– so we'll talk about that. And we'll throw in some other things that we missed the last time around.

And as we stand poised on the precipice of a whole new world, reviewing some of these principles may be more critical than ever.

A Louisiana law has already tried to require the display of the 10 Commandments in all of its public schools; a federal judge just ruled on Tuesday that it was unconstitutional because of a little thing called the 1A, but of course the LA Attorney General is pursuing appeals, and it likely will go all the way to the Christian theocratic SCOTUS, so who knows how things will land, or how many copycat laws we'll see before this is all over.

It behooves us to become all the more educated on these matters.

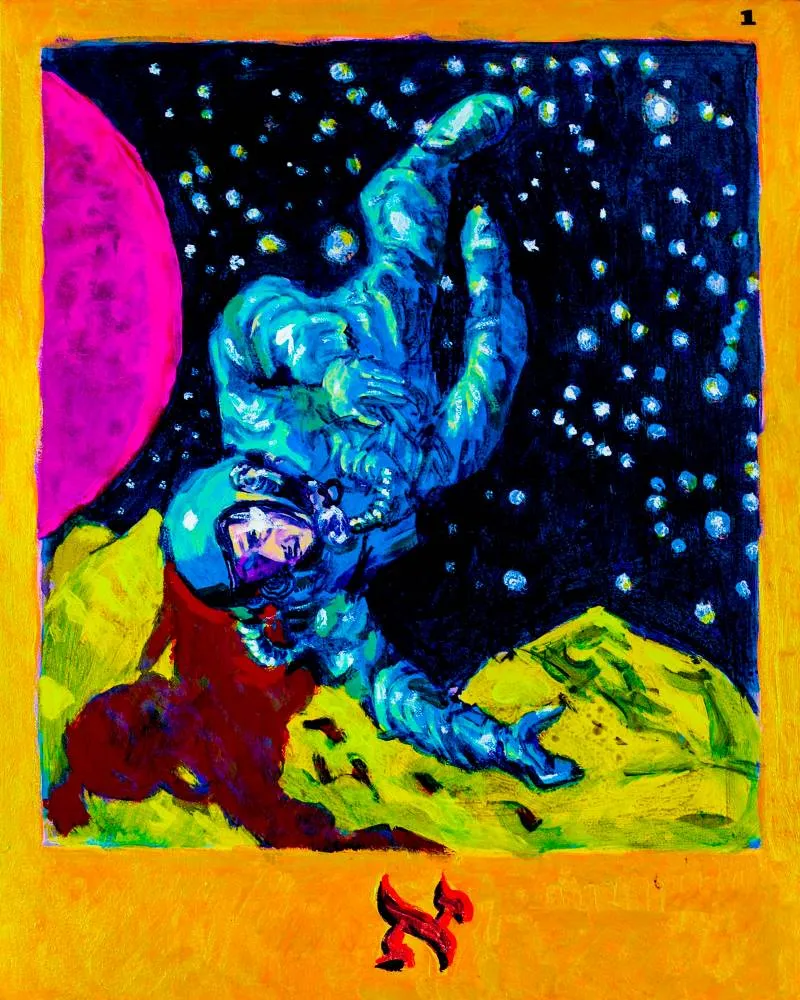

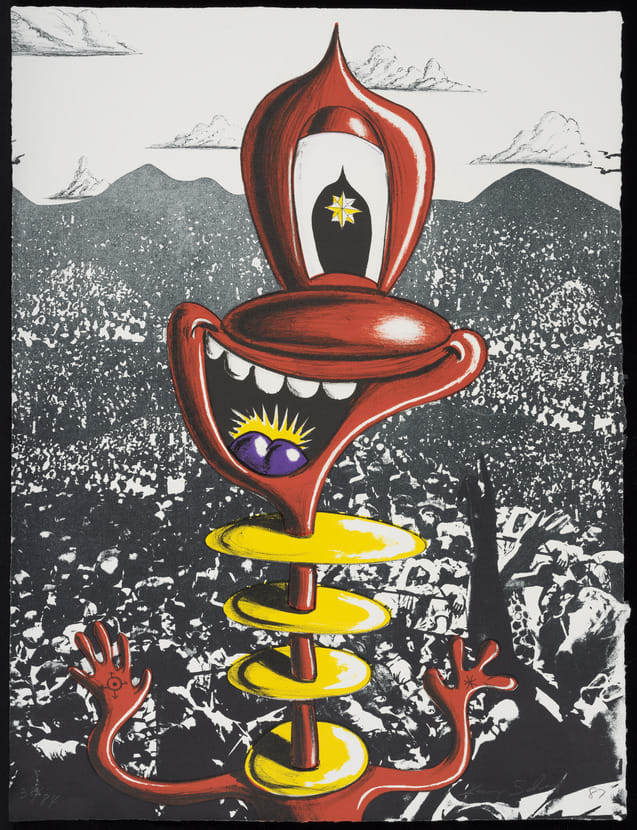

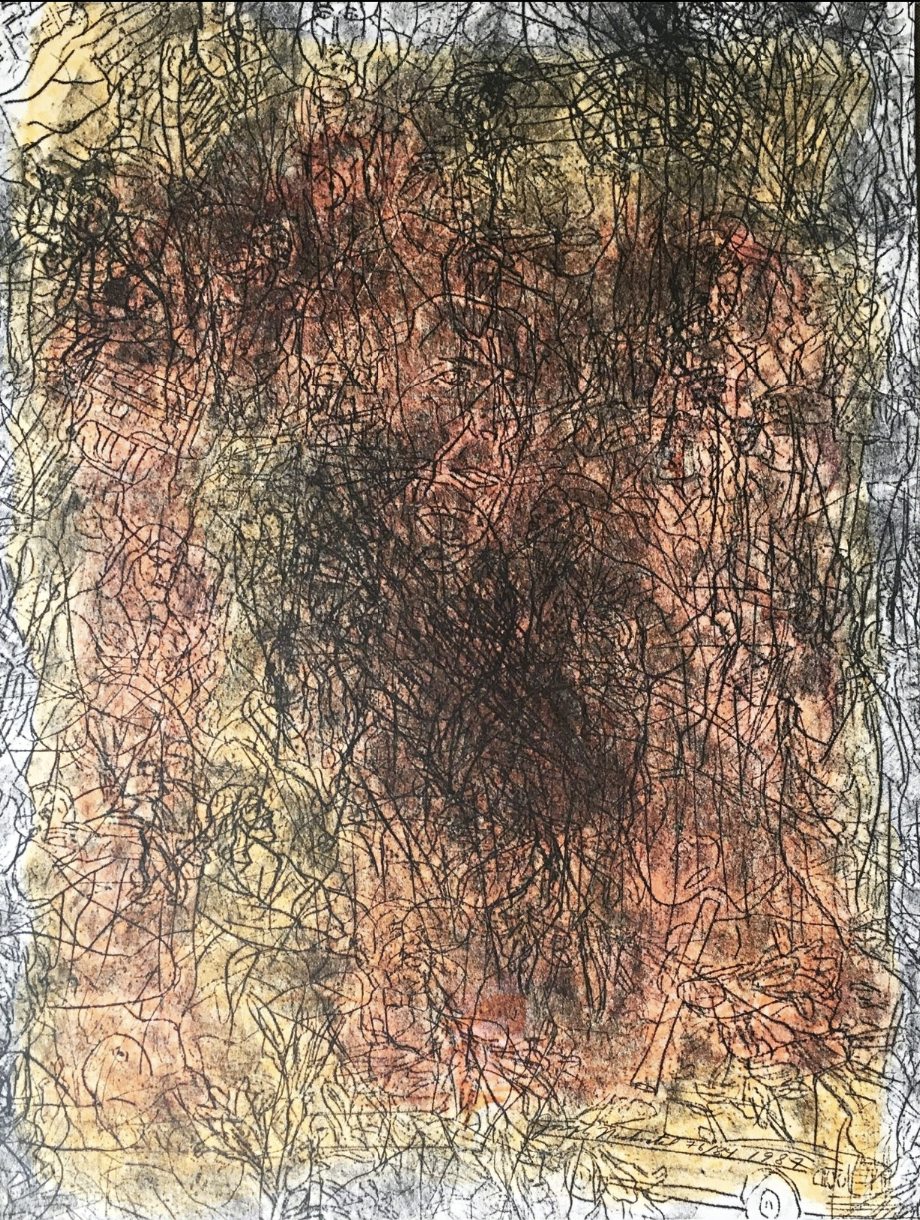

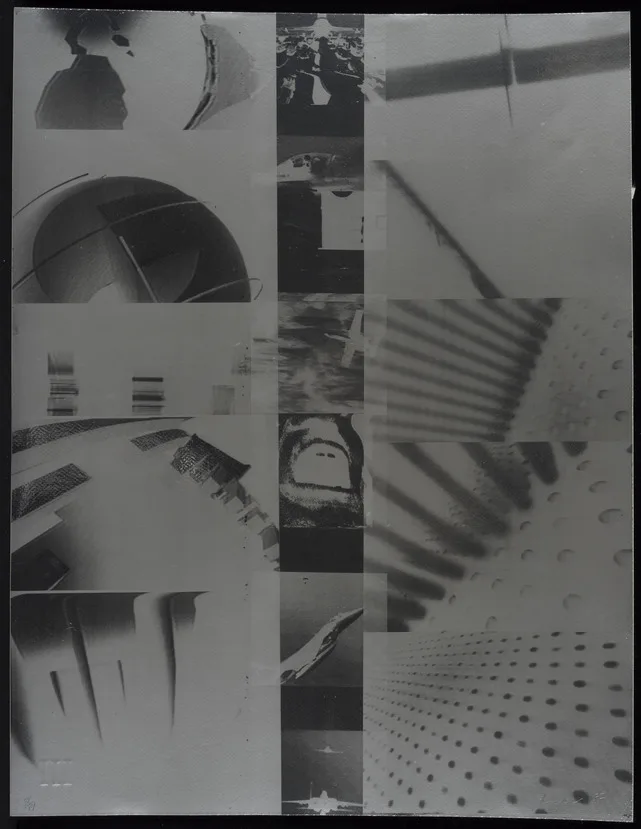

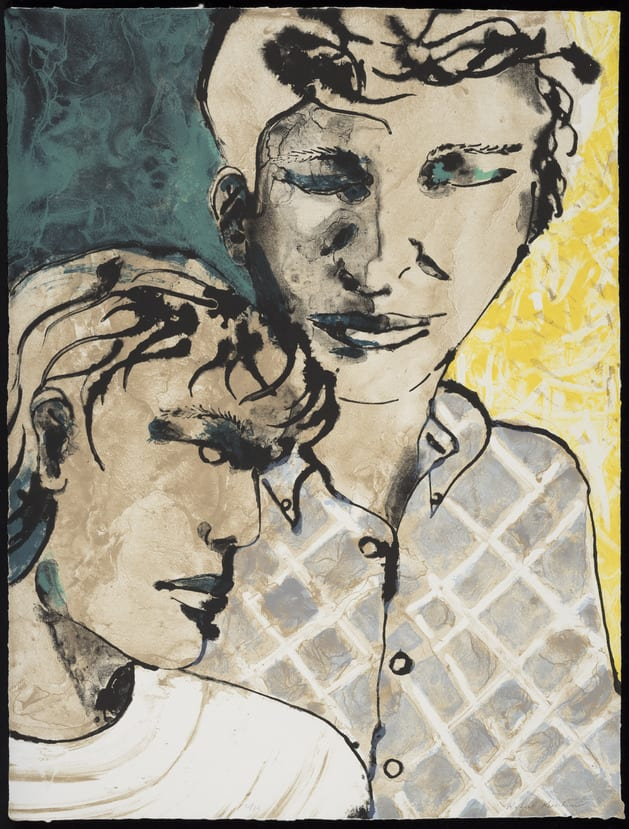

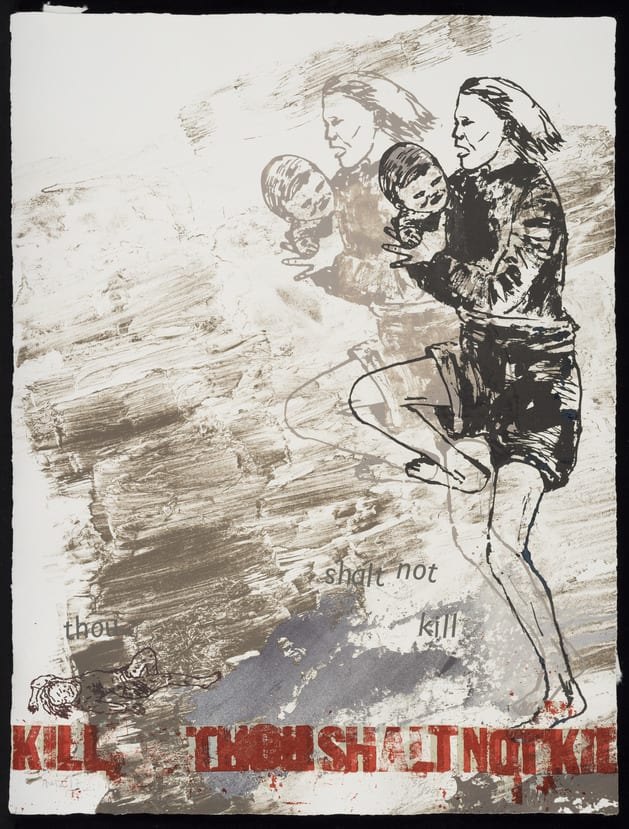

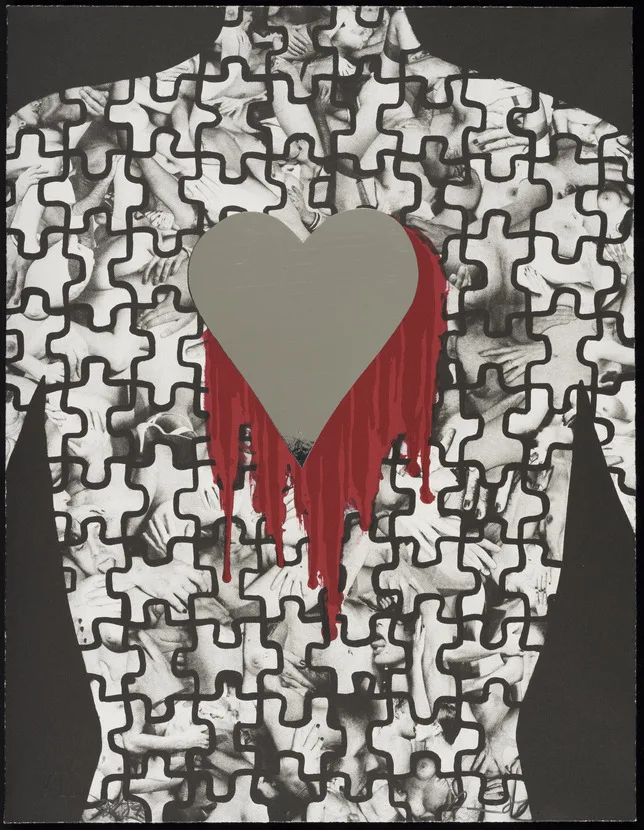

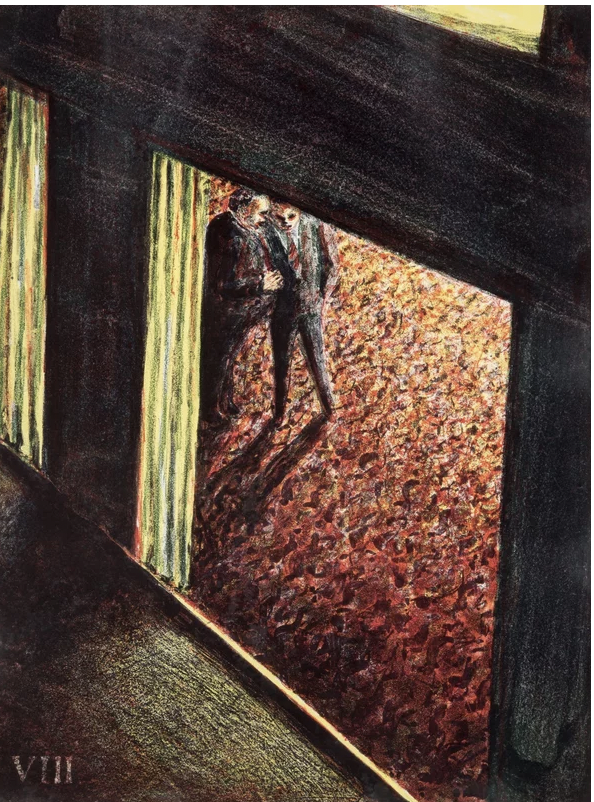

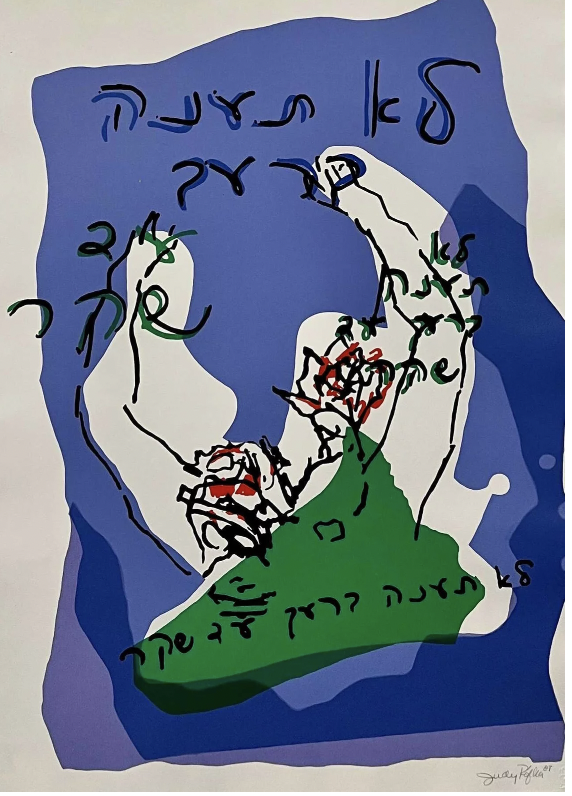

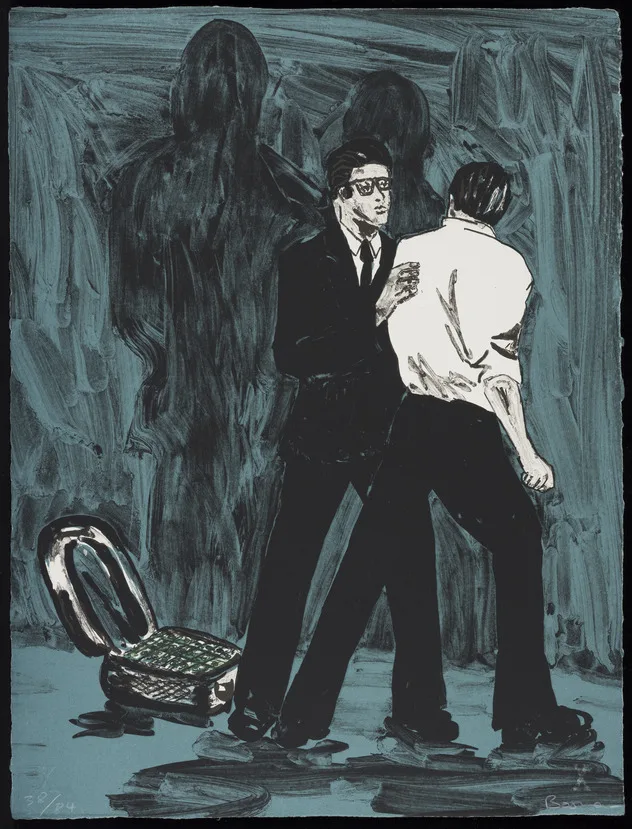

Images below all from a collective project by Jewish contemporary artists in 1987.

We've talked about reading the Torah in layers before, and this is another good place to work that muscle.

Because from the narrative perspective, we have Moses, forty years into a grueling– but probably sometimes peaceful, sometimes boring, sometimes quotidian, sometimes gorgeous– journey through the desert, now telling the children of the Israelites he led out of Egypt what happened at that big mountain that one time.

Our experience telling a story is, necessarily, different than our experience of that thing when it happens. Our memory recounts thing in its own way. And, more to the point: We're different. That we've gone through the thing we're discussing impacts how we make sense of it, to say nothing of other things that may have happened to give us distance, perspective, and/or new insights into what's gone down.

Our needs now are, by definition, not the same as they were, then– we became who we are now by living through then, and our telling about what happened will help us become someone different, tomorrow.

We Jews talk a lot about telling stories, and memory.

They're both cornerstones of our collective identity.

Both are constantly changing. By design.

(How much of this storytelling is about– or meets– Moses' own need to process what has happened?)

And we can hold, at the same time, the historical-critical analysis which posits that the authors of Deuteronomy were likely in the Royal Court of Judea in the 7th-ish c. BCE, bringing that perspective and outlook, whereas the Exodus Big Ten came from– well, it seems that intelligent people disagree about whether they showed up earlier or later in the process, and from where, but there seems (?) to be more consensus that they likely went through editing by P– the priestly authors, and reflect some of their interests as a result.

Relatedly: Exodus calls the mountain Sinai and Deuteronomy calls it Horeb; different biblical authorship strands use different names– J and P say "Sinai;" E and D say "Horeb." Some scholars suggest that Sinai was the desert, and Horeb was the more formal mountain name– and, as such, Exodus was simply referring to the mountain in the Sinai desert. Like if you had two stories about the same event, and one talked about something happening at that big park in Manhattan and the other about it taking place in Central Park. Dig?

As I seem to say again and again:

A lot of things can be true at the same time.

Including, here, the levels on which we plug in.

(And if you missed the first time around, here's the Exodus conversation on 8/10.)

Most of the Ten Words are pretty much the same in Exodus and Deuteronomy, mostly word for word. But where they aren't? Whew.

The biggest differences are in the commandment to keep Shabbat:

| Exodus 20:8-11 | Deuteronomy 5:12-15 |

| Remember the sabbath day and keep it holy. | Guard the sabbath day and keep it holy, as God your God has commanded you. |

| Six days you shall labor and do all your work, | Six days you shall labor and do all your work, |

| but the seventh day is a sabbath of God your God: you shall not do any work—you, your son or daughter, your male or female enslaved-person, or your cattle, or the stranger who is within your settlements. | but the seventh day is a sabbath of God your God; you shall not do any work—you, your son or your daughter, your male or female enslaved-person, your ox or your ass, or any of your cattle, or the stranger in your settlements, so that your male and female enslaved-person may rest as you do. |

| For in six days God made heaven and earth and sea, and all that is in them, and God rested on the seventh day; therefore the God blessed the sabbath day and hallowed it. | Remember that you were enslaved in the land of Egypt and God your God freed you from there with a mighty hand and an outstretched arm; therefore God your God has commanded you to observe the sabbath day. |

In Exodus, we rest because God did. It's a theological position.

In Deuteronomy, we rest because we were enslaved– and the mandate to ensure that those who work for us– our workers, our indentured servants, whatever words you like– are able to rest. "For we were [exactly that thing] in the land of Egypt." And, implied: We didn't get any rest, which is exactly why we should apply our experiences to those who work for us. This, plus all those labor laws throughout the Torah– especially Deuteronomy– are meant to really, really matter.

On one level, we see D's royal court secular humanism vs. P's concern with more transcendent matters.

On another, as Professor Tamara Cohn Eskenazi taught me, we see where the Israelites are in their own story, and what they need to hear.

The people who were just liberated from slavery, still deep in the trauma of enslavement, the plagues, of their narrow escape at the Red Sea– are told that they're allowed, finally, to rest. Like God.

There is a beauty and a softness to it, a gentleness to it that one imagines that someone still adjusting to the experience of freedom might need. This is the natural order of things. You get to be part of the divine rhythm now. The why of resting is that we all do, the natural order of Creation.

And the how? The how is “Remember" the Sabbath day, zachor. According to the Rabbis, it's all the stuff you do to actively celebrate Shabbat – to do things that bring delight, and prayer, and blessing. To actively seek Shabbat’s joy and divine connection.

Forty years later, however, on the edge of a new chapter, Moses gives the Israelites a slightly different message.

This is the next generation; those that suffered the cruelties of Pharaoh are gone, and their children, now adults, are preparing to enter the Promised Land and begin more settled, privileged lives. Do not forget, now the Ten Commandments tells us, from what you were liberated: With freedom, and privilege, comes obligations.

Now we see underscored the obligations to ensure that every worker rests. That nobody will be exhausted and exploited, that the dignity and humanity of every person under their purview will be cherished. The Israelites are no longer newly freed and in need of care. Now they need to be reminded of their roles and obligations, about the imperatives of creating a just society.

And here, the message is: Guard. Shamor. In later Rabbinic understanding, this word refers to all the "don't dos" of Shabbat, aka don't light fires, don't plow, don't weave, etc. Protect the sanctity of the Shabbat space-time for everyone, hold those boundaries–boundaries that are thin and precious, like a shimmering bubble of soap, liable to pop if not managed with care–so that what happens inside that space can be a miraculous sort of quiet, an enchanted stillness, a holy joy, the subtle shift in the air to let you know that it is now sacred time. It’s so quiet, but it’s palpable.

When recovering from or experiencing oppression, when it has been hard, rest is a critical component of liberatory practice. Creating the safe spaces inside the pauses makes those essential celebrations and joy possible in a different way.

And when building a just society, protecting everybody's rights and interests is non-negotiable.

The two versions of the fifth of the Ten Commandments, “Remember the Shabbat day” (Exodus 20:8) and “Keep the Shabbat day” (Deuteronomy 5:12), were spoken by God simultaneously in a single utterance (Talmud Rosh Hashana 27a)

In both versions of Shabbat as one, we have a kind of clarity that spiritual practice and political understandings come together.

Another text goes even further than the trying to harmonize "remember" and "keep," suggesting that God spoke all Ten of the Words/Commandments

“in one utterance, which is impossible for a flesh and blood creature to do.” (Mekhilta, Yitro 20:1)

Ibn Ezra (1089-1167, what's now Spain) doesn't like the "really, they were said at the same time" approach.

Rather, he acknowledges that Moses changed some words from the original Revelation in his retelling. From his vantage,

"The practice of wise people in any language is that they preserve the meaning [of any text] and are unconcerned about changes in wording as long as the meaning stays the same.”

AKA: Moses captured the gist of God's words from Exodus, right?

That's all that matters.

Ramban, Nahmanides (1194-1270, what's now Spain), is not having this "the gist is good enough" approach, and comes in with a skibidi medieval sick burn for Ibn Ezra:

“an explanation like this could only be tolerated by someone who is inexpert in Talmud,”

he says. Ouch.

As long as we're dumping on Ibn Ezra's take here, The Maharal of Prague (Rabbi Judah Loew– yeah, the Golem guy– c. 1525-1609) centuries later said that Ibn Ezra's explanation “gathered up wind [aka emptiness] in his hands.” 😬

⛰️

Reminder that "Do not murder" is the better translation from the Hebrew than "Do not kill."

We know that at least during the Second Temple era, the Decalogue was part of the daily liturgy, but eventually the Rabbis stopped, asserting that the followers of (probably?) Jesus (and/or some other sects that they were subtweeting at the time?) claimed that only the Big Ten were given at Sinai (and not the whole Torah), and the Rabbis evidently worried that including them in daily liturgy could be inadvertently read as supporting that claim.

⛰️

Yeah, adultery in the Torah was really about what a married woman did or didn't do; we all know that, right? What a married man did with his, er, personal effects, was not a matter of interest to this text. We'll talk more about Marriage Things in a handful of weeks.

Here's a piece on the trial of the "suspected adulteress" and a bunch of what it has to do with ancient abortifacients, reproductive coercion, and bad translation.

Both ancient and medieval rabbinic commentaries, as well as some contemporary scholarship suggests that "Do not steal" likely isn't about just a basic case of the Five Finger Discount.

(They look at both how various verbs for theft are used in the Torah and the fact that most of these Big 10 carry pretty weighty consequences in the Torah, and other things.)

(Which isn't to say that theft is permitted! It's explicitly forbidden elsewhere!)

Rather, these voices argue, it's likelier that lo tignov here was assumed to mean, "do not steal people," aka "do not kidnap." Because sometimes that verb talks about that, too.

The ninth commandment is generally translated the same way in Exodus and Deuteronomy: "You shall not bear false witness against your neighbor."

But you can see from the Hebrew, below, they're not the same word– Exodus tells us not to give testimony that is sheker– lying, deceptive, false. Deuteronomy says not to give testimony that is shav – empty, vain, worthless, nothingness. A subtle difference, but a difference nonetheless.

לֹא־תַעֲנֶה בְרֵעֲךָ עֵד שָׁקֶר׃

You shall not give deceptive testimony against your neighbor. (Exodus 20:13)

וְלֹא־תַעֲנֶה בְרֵעֲךָ עֵד שָׁוְא׃

You shall not give worthless testimony against your neighbor. (Deuteronomy 5:17)

Nahmanides says that the commandment in Deuteronomy prohibits giving false testimony even when the neighbor couldn't possibly be hurt – and is, as such, "worthless" in court. Exodus, on the other hand, is about testimony that truly intends to harm the other party.

Rabbi Jacob ben Asher (What's now Germany, c. 1269 - c. 1343) has a similar, but slightly different read on this, saying that Exodus forbids testimony that is "untrue, false,"

"whereas Moses here appears to expand the prohibition to someone who testifies to something irrelevant, something vain, something which is not enforceable by a court of law, for instance. Frivolous testimony, which may only serve to undermine one of the parties’ good reputation is prohibited by the Torah, also..."

In any case, they're not the same thing, and shouldn't be understood as such.

Needless to say, Rabbinic thinking would run that if you can't give frivolous or worthless testimony, you definitely can't give harmful testimony, so the prohibition of Exodus is presumed to be contained in the prohibition of Deuteronomy.

The last commandment is also slightly different in Exodus and Deuteronomy.

The latter:

You shall not covet/תחמֹד your neighbor’s wife. And you shall not crave/תתאוה your neighbor’s house, or field, or male and female enslaved-people (or: worker and handmaid) or ox, or donkey, or anything that is your neighbor’s. (Deuteronomy 5:18)

In Exodus, everything is about not covet/תחמֹד-ing– that verb is repeated in the second sentence, and crave/תתאוה does not appear at all.

(To keep things confusing, the King James translation makes it seem as though the Exodus passage shares a verb with the second verse, rather than the first verse).So what's the difference?

Let's start by trying to understand the Exodus passage, wherein we worry only about חמד.

We can look to, eg, Micah 2:2 for clues that, perhaps, this is less about feelings than action.

covet/חמדוּ fields, and seize/steal them; houses, and take them away. They defraud men of their homes, And people of their land.

The חמד-ing is connected to seizing/stealing, taking, defrauding.

And the most commonplace way that someone might do this– then, as now–may have been through the violence of aggressive debtor practices. That is: predatory loan systems that end in those unable to pay back having their property seized. As Bible scholar Marvin L. Chaney put it,

“the tenth commandment, when understood in biblical history ... forbade forms and practices of land consolidation so aggressive and coercive that they deprived a family of fellow Israelites of their ancestral plot of arable land and the subsistence and social inclusion that it supported."

And in this context, not coveting one's neighbor's wife probably wasn't (contrary to popular belief) necessarily sexual! But, rather, about not seizing her for indentured servitude.

Thou shalt not set up predatory economic systems.

How about that.

Generally speaking, Jewish commentators translate the not craving/תתאוה of Deuteronomy as the not-thinking-about-the-thing– as people often think about "covet." but even then, it's less about how if you have one flash of an emotion you're forever BAD BAD BAD. Rather, says Rabbi Jacob ben Asher, the influential 13th-14th c. German legal authority known as the Tur, one shouldn't "daydream" about doing the actions of חמד.

Don't exploit. AND don't even think about how you might do it.

Because that's the pathway to actually doing the horrible thing, many Jewish commentators say. Don't think about the harm you could do, don't give yourself mental pathways or opportunities.

Perhaps over the forty years of desert tribulations since the Revelation at Sinai, Moses had learned a bit about human nature. Perhaps he had discovered that, when it comes to our tendency towards exploitation, we must be especially scrupulous, and might need some extra help.

The dangers are ever-present, and there is so much at stake.

“Face to face God spoke with you” (Deuteronomy 5:4). Rabbi Levi said: “My God is in their midst” (Psalms 68:18). This means that [when God gave the Big Ten at Sinai] there was a tablet with the Ineffable Name inscribed over [the Israelites'] hearts. (Midrash Exodus Rabbah 29:2)

🌱

Like this? Get more of it in your inbox every week.

For free every Monday—sign up at the ‘Subscribe now’ button just below.

And if you become a paid subscriber, that's how you can get tools for deeper transformation, a community for doing the work, and support the labor that makes these Monday essays happen.

A note on the subscription model:

I want my work to be as accessible to as many people as possible, in as many ways as possible. That's why the Monday essays are free, and why we donate subscriptions to anyone for whom paying is a barrier to the House of Study posts.

I also believe people should be paid fairly for their work. Needless to say, these two values sometimes seem to be in conflict, but I do what I can to find a fair balance. I offer many resources for free, and charge for others. When you donate generously or pay at the top of our scale, that helps support the work I do, provides access for those who have fewer resources, pays for the infrastructure and the technical and practical support that it takes to do this, and helps us keep the work sustainable.

And as always, if you want in to the Thursday space but paying isn't for you now, just email support@lifeisasacredtext.com and we'll hook you up.

And if you’d like to underwrite one of these donated subscriptions, you can do so by signing up at one of the higher subscription points.

And if it resonated with you, please share this post.

Sending a big pile of blessings and goodness your way. 💕